Kenji Doihara

Article

Talk

Read

Edit

View history

Tools

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Doihara Kenji

Doihara in c. 1941~45

Nickname(s) Lawrence of Manchuria, a reference to T. E. Lawrence

Born 8 August 1883

Okayama, Japan

Died 23 December 1948 (aged 65)

Sugamo Prison, Tokyo, Occupied Japan

Cause of death Execution by hanging

Allegiance Empire of Japan

Service/branch Imperial Japanese Army

Years of service 1904–1945

Rank General

Commands held 14th Division

Fifth Army

Seventh Area Army

Battles/wars Siberian Intervention

Second Sino-Japanese War

World War II

Awards Order of the Rising Sun

Kenji Doihara (土肥原 賢二, Doihara Kenji, 8 August 1883 – 23 December 1948) was a Japanese army officer. As a general in the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II, he was instrumental in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria.

As a leading intelligence officer, he played a key role to the Japanese machinations that led to the occupation of Manchukuo and he became the leader of the Manchukuo drug trade after taking over the market.

After the end of World War II, he was prosecuted for war crimes in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. He was found guilty, sentenced to death, and hanged in December 1948.

Early life and career

Doihara in army cadet uniform, 1903

Assassination of Zhang Zuolin, 4 June 1928

Kenji Doihara was born in Okayama City, Okayama Prefecture. He attended military preparatory schools as a youth, and graduated from the 16th class of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1904. He was assigned to various infantry regiments as a junior officer, and returned to school to graduate from the 24th class of the Army Staff College in 1912.

Doihara longed for a high-ranking military career, but his family's low social status stood in the way. He therefore contrived to use his 15-year-old sister as a concubine for a prince, who in exchange, rewarded him with a military rank and a posting to the Japanese embassy in Beijing as assistant to the military attaché General Hideki Tōjō.[1][2][3] After that, Doihara quickly rose within the ranks of the army. He spent most of his early career in various postings in northern China, except for a brief tour in 1921-1922 as part of the Japanese forces in eastern Russia during the Siberian Intervention. He was attached to IJA 2nd Infantry Regiment from 1926 to 1927 and IJA 3rd Infantry Regiment in 1927. In 1927, he was part of an official tour to China and then attached to IJA 1st Division from 1927 to 1928.

He learned to speak fluent Mandarin Chinese, and with this, he managed to take a position in military intelligence. From that post in 1928, it was he who masterminded the assassination of Zhang Zuolin, the Chinese warlord who controlled Manchuria, devising a scheme to detonate Zuolin's train as it traveled from Beijing to Shenyang. After that he was made military adviser to the Kuomintang Government until 1929. In 1930, he was promoted to colonel and commanded IJA 30th Infantry Regiment.

Member of the "Eleven Reliable" clique

Doihara's performance was recognized, and by 1930 he was assigned to the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office. There, together with Hideki Tojo, Seishirō Itagaki, Daisaku Komoto, Yoshio Kudo, Masakasu Matsumara and others, he became a chosen member of the "Eleven Reliable" circle of officers. The Eleven Reliable clique was an external tool of a more closed group of three influential senior military officers called the "Three Crows" (Tetsuzan Nagata, Yasuji Okamura and Toshishiro Obata) who wanted to modernize the Japanese military and to purge it of its anachronistic samurai tradition and the dominant allied clans of Chōshū and Satsuma that favored that tradition. The real sponsor behind both two bodies was Field Marshal Royal Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni, uncle and advisor of the Emperor Hirohito, and responsible for eight fake coups d'état, four assassinations, two religious hoaxes, and countless threats of murder and blackmail between 1930 and 1936 in his effort to neutralize the Japanese moderates, who opposed war, by spreading terror.[citation needed] Higashikuni highly favored covered work by faithful officers inside the intelligence departments in order to bring about the political program of his own clique named Tōseiha. This clique had a decisive materialistic, westernizing approach on the issue of the Empire's expansion, in a rather colonization-like fashion, as opposed to the rival Kōdōha clique which was for a more "spiritual" way of expansion as an effort to liberate and unite all Asian peoples under a racial, not nationalistic Empire. Kōdōha, headed by Gen. Sadao Araki, under the national socialistic, totalitarian and populistic philosophical influence of Ikki Kita charged Tōseiha for collusion with the Zaibatsu financial conglomerate business clique, or to simply put it, for amoralism and pro-capitalism.[4] It is not quite clear whether Doihara joined the movement for ideological or opportunistic reasons, but in any case, from then on his military career accelerated. In 1931, he became head of the military espionage operations of the Japanese Army of Manchuria in Tianjin. The following year, he was transferred to Shenyang as head of the Houten Special Agency, the military intelligence service of the Japanese Kwantung Army.

"Lawrence of Manchuria”

A section of the Liǔtiáo railway where Suemori Komoto under Doihara's orders planted the bomb that triggered the Japanese invasion in Manchuria. The caption reads "railway fragment".

Harvest of poppy in Manchukuo used for opium production

While at Tianjin, Doihara, together with Seishirō Itagaki engineered the infamous Mukden Incident by ordering Lieutenant Suemori Komoto to place and fire a bomb near the tracks at the time when a Japanese train passed through. In the event, the bomb was so unexpectedly weak and the damage of the tracks so negligible that the train passed undamaged, but the Imperial Japanese Government still blamed the Chinese military for an unprovoked attack, invaded and occupied Manchuria. During the invasion, Doihara facilitated the tactical cooperation between the Northeastern Army Generals Xi Qia in Jilin, Zhang Jinghui in Harbin and Zhang Haipeng at Taonan in the northwest of Liaoning province.

Next, Doihara took the task to return former Qing dynasty Emperor Puyi to Manchuria as to give legitimacy to the puppet regime. The plan was to pretend that Puyi had returned to resume his throne due to imaginary popular demand of the people of Manchuria and that although Japan had nothing to do with his return, it could do nothing to oppose the will of the people. To carry out the plan, it was necessary to land Puyi at Yingkou before that port froze; therefore, he had to arrive there before 16 November 1931. With the help of the spy Kawashima Yoshiko, a relative of Puyi, he succeeded in bringing him into Manchuria within the deadline.

In early 1932, Doihara was sent to head the Harbin Special Agency of the Kwantung Army, where he began negotiations with General Ma Zhanshan after he had been driven from Qiqihar by the Japanese. Ma's position was ambiguous; he continued negotiations while he supported Harbin-based General Ding Chao. When Doihara realized his negotiations were not going anywhere, he requested that Manchurian warlord Xi Qia advance with his forces to take Harbin from General Ding Chao. However, General Ding Chao was able to defeat Xi Qia's forces, and Doihara realized he would need Japanese forces to succeed. Doihara engineered a riot in Harbin to justify their intervention. That resulted in the IJA 12th Division under General Jirō Tamon coming from Mukden by rail and then marching through the snow to reinforce the attack. Harbin fell on 5 February 1932. By the end of February, General Ding Chao retreated into northeastern Manchuria and offered to cease hostilities, ending Chinese formal resistance in Manchukuo. Within a month, the puppet state of Manchukuo was established under Doihara's supervision who had named himself mayor of Mukden. He then arranged for the puppet government to ask Tokyo to supply "military advice". During the next months 150,000 soldiers, 18,000 gendarmes and 4,000 secret police came into the newly founded protectorate. He used them as an occupying army, imposing slave labour and spreading terror to force the 30 million Chinese inhabitants into abject submission.[5]

Ma's fame as an uncompromising fighter against the Japanese invaders survived after his defeat and so Doihara made contact with him offering a huge sum of money and the command of the puppet state's army if he would defect to the new Manchurian government. Ma pretended that he agreed and flew to Mukden in January 1932, where he attended the meeting on which the state of Manchukuo was founded and was appointed War Minister of Manchukuo and Governor of Heilongjiang Province. Then, after using the Japanese funds to raise and re-equip a new volunteer force, on 1 April 1932, he led his troops to Qiqihar, re-establishing the Heilongjiang Provincial Government as part of the Republic of China and resumed the fight against the Japanese.

From 1932 to 1933, the newly promoted Major General Doihara commanded IJA 9th Infantry Brigade of IJA 5th Division. After the seizure of Rehe in Operation Nekka, Doihara was sent back to Manchukuo to head Houten Special Agency once again until 1934. He was then attached to IJA 12th Division until 1936.

For the key role he played in the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, he earned the nickname "Lawrence of Manchuria," a reference to Lawrence of Arabia. However, according to Jamie Bisher, the flattering sobriquet was rather misapplied, as that Colonel T.E. Lawrence had fought to liberate, not to oppress people.[6]

Criminal activities

As chief of the Japanese secret services in Manchukuo, he worked out, put in motion, and oversaw a wide series of activities including taking over the already existing Manchurian drug trade and its revenue.[7]

He initially gave food and shelter to tens of thousands of Russian White émigré women who had taken refuge in the Far East after the defeat of the White Russian anti-Bolshevik movement during the Russian Civil War and the withdrawal of the Entente and Japanese armies from Siberia. Having lost their livelihoods, and with most of them widowed, Doihara forced the Russian women into prostitution, using them to create a network of brothels throughout Manchukuo where they worked under inhuman conditions. The use of heroin and opium was promoted to them as a way to tolerate their miserable fate. Once addicted, the Russian women were used to further spread the use of opium among the population by earning one free opium pipe for every six they were selling to their customers. Doihara addicted White Russians to narcotics to force them to work for him as agents in his takeover of Manchukuo.[8]

Chinese already consumed major amounts of opium over a century before the war with Japan and all Chinese factions like the warlords and Kuomintang themselves used opium trafficking as revenue while fighting against Japan. The warlord Zhang Zuolin who ruled Manchuria before Japan's invasion of Manchuria and establishment of Manchukuo himself used opium. Local Chinese triads took over the opium market in China from the British after the Opium wars and most of the money earned by opium trafficking in China went to local Chinese factions. Chinese triads and warlords and Kuomintang both grew their own opium in China and imported foreign Persian opium. Doihara and other Japanese did not introduce opium addiction or trafficking to China but tried to cut into the already established opium drug market and tap it for revenue to finance Japan. According to the Tokyo tribunal, Japan began by seizing a shipment of Persian opium that was being imported into China by Chinese and used it to finance Manchukuo. Winning the necessary support from the authorities in Tokyo he persuaded the Japanese tobacco industry Mitsui of Mitsui Zaibatsu to produce special cigarettes bearing the popular to the Far East trademark "Golden Bat". Their circulation was prohibited in Japan, as they were intended only for export. Doihara's services controlled their distribution in Manchuria where the full production was exported. In the mouthpiece of each cigarette a small dose of heroin was concealed. According to testimony presented at the Tokyo War Crimes trials in 1948, the revenue from the narcotization policy in Manchukuo, China, was estimated as twenty to thirty million yen per year, while another authority[who?] stated during the trial that the annual revenue was estimated by the Japanese military at 300 million dollars a year.[9]

The post-war Tokyo International Military Tribunal of the Far East accused the Japanese like Doihara of using Manchukuo as a proxy front to sell drugs to places all over the world in order to raise money, instead of doing selling them directly from Japan to avert blame.

Second Sino-Japanese War and Second World War

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Kenji Doihara" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (November 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Doihara in a press photo in Tokyo during 1936, by then a Lt. General

From 1936 to 1937, Doihara was the commander of the 1st Depot Division in Japan until the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, when he was given command of the IJA 14th Division under the Japanese First Army in North China. There, he served in the Beiping–Hankou Railway Operation and spearheaded the campaign of Northern and Eastern Henan, where his division opposed the Chinese counterattack in the Battle of Lanfeng.

After the Battle of Lanfeng, Doihara was attached to the Army General Staff as head of the Doihara Special Agency until 1939, when he was given command of the Japanese Fifth Army, in Manchukuo under the overall control of the Kwantung Army.

In 1940, Doihara became a member of the Supreme War Council.[10] He then became head of the Army Aeronautical Department of the Ministry of War, and Inspector-General of Army Aviation until 1943. From 1940 to 1941, he was appointed Commandant of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. On 4 November 1941, as a general in the Japanese Army Air Force and a member of the Supreme War Council he voted his approval of the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In 1943, Doihara was made Commander in Chief of the Eastern District Army. In 1944, he was appointed the Governor of Johor State, Malaya, and commander in chief of the Japanese Seventh Area Army in Singapore until 1945.

Returning to Japan in 1945, Doihara was promoted to Inspector-General of Military Training (one of the most prestigious positions in the Army) and commander in chief of the Japanese Twelfth Area Army. At the time of the surrender of Japan in 1945, Doihara was commander in chief of the 1st General Army.

Prosecution and conviction

His arrest, accused for war crimes

During his trial before the International Military Tribunal of the Far East. First in the front row from left to right

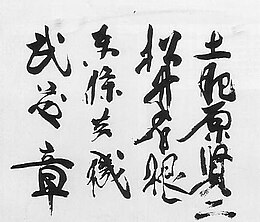

Last writing of the Class-A War Criminals (Kenji Doihara, Iwane Matsui, Hideki Tojo and Akira Muto)

Kenji Doihara in 1948

After the surrender of Japan, he was arrested by the Allied occupation authorities and tried before the International Military Tribunal of the Far East as a Class A war criminal together with other members of the Manchurian administration responsible for the Japanese policies there. He was found guilty on counts 1, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 36, and 54 and was sentenced to death, while his close colleague Naoki Hoshino, financial expert and director of the Japanese State Opium Monopoly Bureau in Manchuria, was sentenced to life imprisonment. According to the indictment, as tools of successive Japanese governments they: "... pursued a systematic policy of weakening the native inhabitants' will to resist ... by directly and indirectly encouraging the increased production and importation of opium and other narcotics and by promoting the sale and consumption of such drugs among such people." The indictment also stated "The principle sources of opium and narcotics at the time of the Mukden Incident and for some time thereafter, was Korea, where the Japanese Government operated a factory in the town of Seoul for the preparation of opium and narcotics. Persian opium was also imported into the Far East. The Japanese Army seized a huge shipment of this opium, amounting to approximately 10 million ounces, and stored it in Formosa in 1929; this opium was to be used later to finance Japan's military campaigns. There was another source of illegal drugs in Formosa. The cocaine factory operated at Sinei by Finance Minister Takahashi of Japan until his assassination in 1936, produced from 200 to 300 kilos of cocaine per month. This was one factory that was given specific authority to sell its produce to raise revenue for war" and "Japan, having signed and ratified the opium conventions, was bound not to engage in drug traffic, but she found in the alleged but false independence of Manchukuo a convenient opportunity to carry on a worldwide drug traffic and cast the guilt upon that puppet State. A large part of the opium produced in Korea was sent to Manchuria. There, opium grown in Manchuria and imported from Korea and elsewhere, was manufactured and distributed throughout the world. In 1937, it was pointed out in the League of Nations that ninety per-cent of all illicit white drugs in the world were of Japanese origin..."[11] He was hanged on 23 December 1948 at Sugamo Prison.[12]

See also

Japanese war crimes

References

Encyclopedia of War Crimes And Genocide, p.127, Facts on File, Leslie Alan Horvitz & Christopher Catherwood, ISBN 9780816060016, 2006

Encyclopedia of espionage, p.313, Ronald Sydney Seth, ISBN 9780385016094, Doubleday, 1974

The Enemy Within: A History of Espionage, p.221, Terry Crowdy, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 9781846032172, 2008

Sims, Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Renovation 1868–2000

White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian,p.299, Jamie Bisher, Routledge, ISBN 9780714656908, 2005

Bisher, Jamie (2005). White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian. Routledge. p. 359. ISBN 0-714-65690-9.

The peace conspiracy: Wang Ching-wei and the China war, 1937-1941, vol. 67, Harvard East Asian Series, The East Asian Research Center at Harvard University, Harvard University Press, 1972

White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian,p.298, Jamie Bisher, Routledge, ISBN 978-0714656908, 2005

Mitsui: Three Centuries of Japanese Business, pages 312-313, John G. Roberts, Weatherhill, 1991, ISBN 9780834800809

Fairbank, J. K.; Goldman, M. (2006). China: A New History (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 320. ISBN 9780674018280.

The Opium Empire: Japanese Imperialism and Drug Trafficking in Asia, 1895-1945, John M. Jennings, p.102, Praeger, 1997, ISBN 0275957594

Maga, Judgment at Tokyo

Books

Beasley, W.G. (1991). Japanese Imperialism 1894–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822168-1.

Barrett, David (2001). Chinese Collaboration with Japan, 1932–1945: The Limits of Accommodation. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3768-1.

Bix, Herbert P. (2001). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-093130-2.

Fuller, Richard (1992). Shokan: Hirohito's Samurai. London: Arms and Armor. ISBN 1-85409-151-4.

Hayashi, Saburo; Cox, Alvin D (1959). Kogun: The Japanese Army in the Pacific War. Quantico, VA: The Marine Corps Association.

Maga, Timothy P. (2001). Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2177-9.

Minear, Richard H. (1971). Victor's Justice: The Tokyo War Crimes Trial. Princeton, NJ, USA: Princeton University Press.

Toland, John (1970). The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945. Random House. ISBN 0-8129-6858-1.

Wasserstein, Bernard (1999). Secret War in Shanghai: An Untold Story of Espionage, Intrigue, and Treason in World War II. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-98537-4.

External links

Ammenthorp, Steen. "Kenji Doihara". The Generals of World War II.

"Scholar, Simpleton & Inflation". Time Magazine. 1932-04-25. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

Newspaper clippings about Kenji Doihara in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。