武士道這個詞讓人聯想到日本神聖的武士階級的幽靈。

這個階級如此熱衷於維護榮譽,他們寧願以儀式性的自殺方式剖腹自殺,也不願過著恥辱的生活。

在《最後的武士》中,武士道與內森·阿爾格倫的靈魂融為一體,治癒了飽受酗酒、戰爭創傷和自我厭惡困擾的美國人。

多麼厲害的藥啊!重獲新生、淨化的阿爾格倫背棄了雇主,加入了反叛武士,一心捍衛武士道,即忠誠、仁慈、禮儀和自製的尊嚴榮譽準則。

至少,流行文化讓我們相信這一點。事實上,直到二十世紀初,內森·阿爾格倫(Nathan Algren)的虛構角色加入了真實的薩摩叛亂很久之後,以及武士階級被驅逐多年之後,“武士道”一詞才得到認可。武士很可能從未說過這個字。

更令人驚訝的是,武士道曾經在國外獲得的認可比在日本還要多。

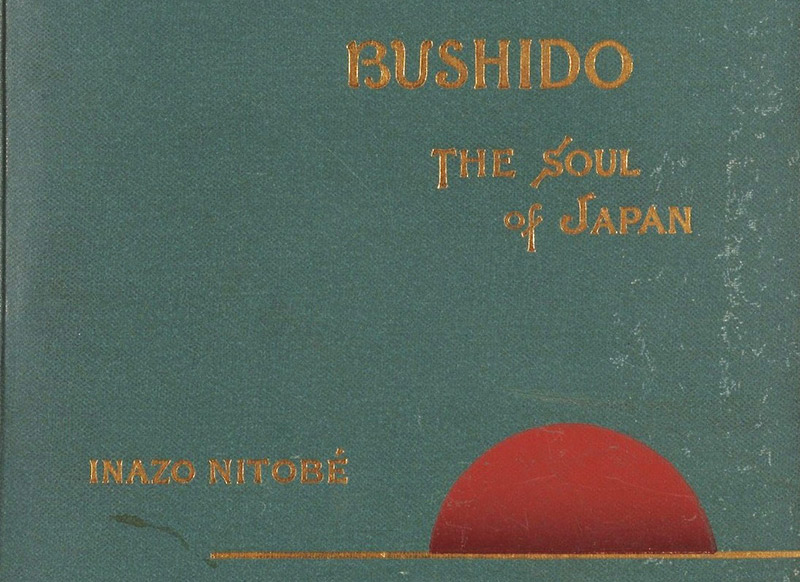

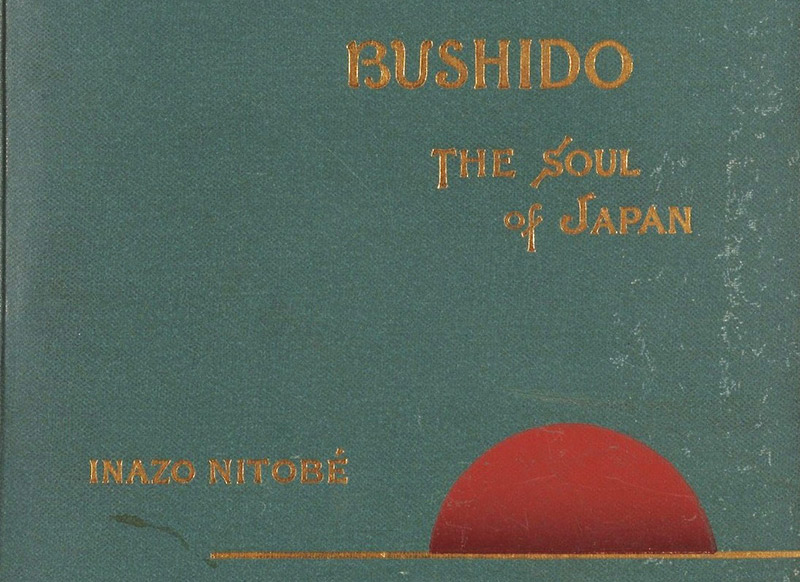

1900 年,作家新渡戶稻造為西方讀者出版了英文版《武士道:日本之魂》 。

新渡戶顛覆了事實,對日本文化和過去進行了理想化想像,向日本武士階級注入基督教價值觀,希望塑造西方對其國家的解讀。

儘管新渡戶的思想最初在日本遭到拒絕,但後來被政府驅動的戰爭機器所接受。由於其對過去的賦權願景,極端民族主義運動擁抱了武士道,利用「日本之魂」為日本在第二次世界大戰前的法西斯主義鋪平了道路。

《最後的武士》也利用了新渡戶稻造對武士道的描繪,讓電影觀眾重新對這個古老的概念和從未真正存在過的輝煌過去表示欽佩。但正如武士道不穩定的歷史所證明的那樣,真相往往讓位給更時尚的描述,無論是為了改變西方的看法,推動法西斯戰爭議程,還是出售電影票。

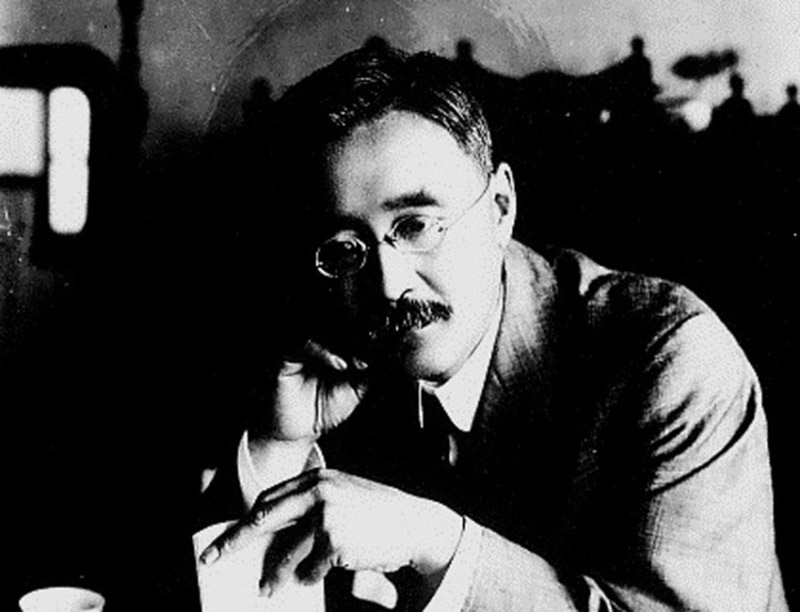

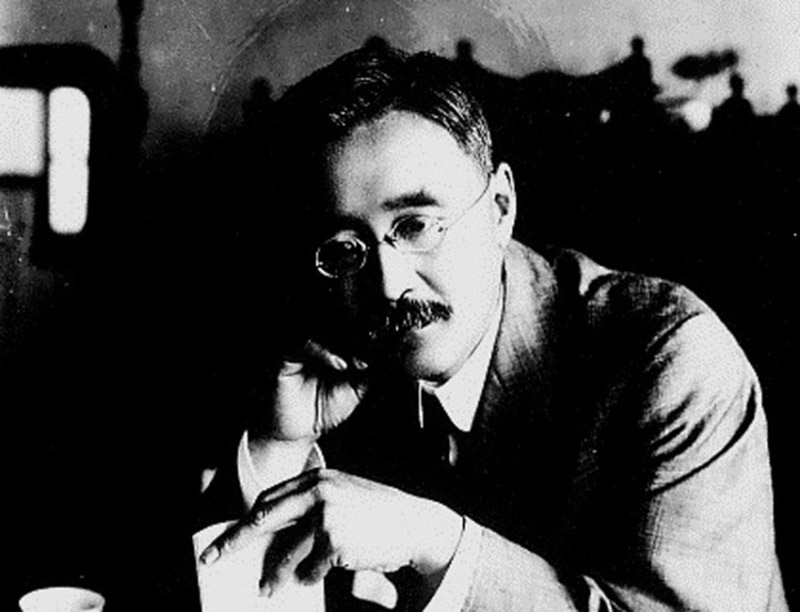

新渡戶稻造

新渡戶稻造 (Inazo Nitobe) 1862 年出生於岩手縣,當時日本統治武士階級最後的殘餘勢力已經結束,他還只是個嬰兒。儘管新渡戶家族本身屬於武士階層,但他們仍然遠離舊日本的戰場和武士文化,被認為是灌溉和農業技術的先驅。

九歲時,新渡戶搬到東京與叔叔住在一起,在那裡他開始強化英語學習。新渡戶的語言在當時是一個獨特的研究主題,他後來變得流利。卡梅倫赫斯特在《死亡、榮譽與忠誠:武士道理想》一書中寫道:「新渡戶是已故德川武士的基督徒兒子…他在明治初期的特殊學校主要接受英語教育…他可以在某種程度上與外國人交流即使是當今國際化最熱心的倡導者也會羨慕」(511)。

1877年,新渡戶前往北海道,就讀札幌農學院。該學校是在來自新英格蘭的虔誠加爾文主義者威廉·S·克拉克(William S. Clark)的影響下創建的,它進一步鞏固了新渡戶對基督教信仰的承諾,他加入了克拉克自己的基督徒「札幌樂團」(Oshiro)。

在札幌,新渡戶與日本社會、文化和人民的疏離與日俱增。日本最北端的島嶼基本上仍然是無人居住的荒野,與日本大陸幾乎沒有文化聯繫。 「北海道才剛成為日本真正的一部分,」赫斯特寫道,「因此新渡戶在空間、文化、宗教甚至語言上基本上與明治日本的潮流隔絕」(512)。

從札幌農學院畢業後,新渡戶開始在東京攻讀研究所。由於對學業不滿意,新渡戶於 1884 年移居美國,就讀於約翰霍普金斯大學。畢業後,環遊世界的新渡戶輾轉德國、美國和札幌,甚至成為國際聯盟副秘書長(山繆·史奈普斯 Samuel Snipes 飾)。

即使以今天的標準來看,新渡戶對英國和西方文學的了解仍然令人印象深刻,這在他的時代是獨一無二的。深入研究《武士道:日本明治晚期武士道德的建立》一書的作者奧列格·貝內什寫道,新渡戶“比日語更擅長使用英語”,並最終“感嘆自己缺乏日本歷史和宗教方面的教育」 (159)。

新渡戶在加州期間寫了《武士道:日本之魂》。對武士階級的人為想像重塑了西方對日本的看法,並最終重新定義了日本自己對武士道和武士階級的解釋。

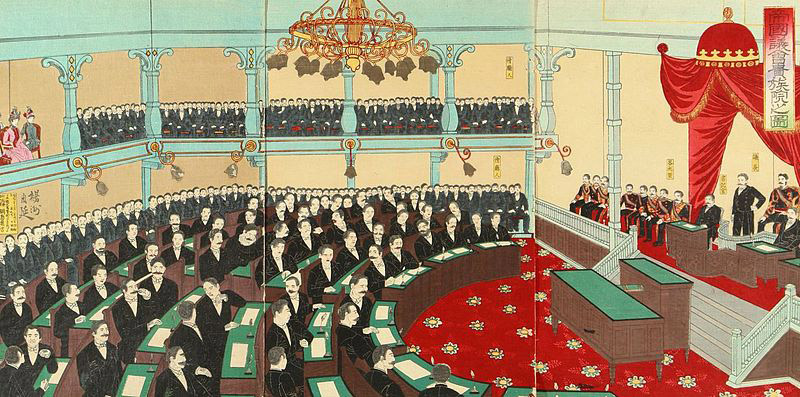

追趕:明治維新

在新渡戶沉浸於西方宗教和文化的同時,日本政府仍在繼續自己的國際追求——現代化。 GRIPS 的 Kenichi Ohno 教授解釋說,「國家的首要任務是在文明的各個方面趕上西方,即盡快成為『一流國家』」(43)。

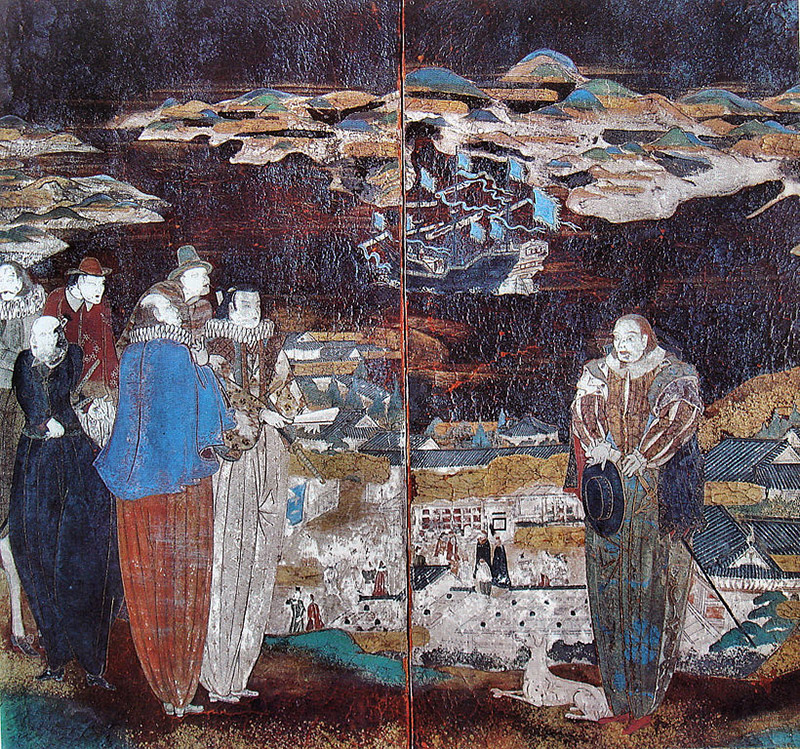

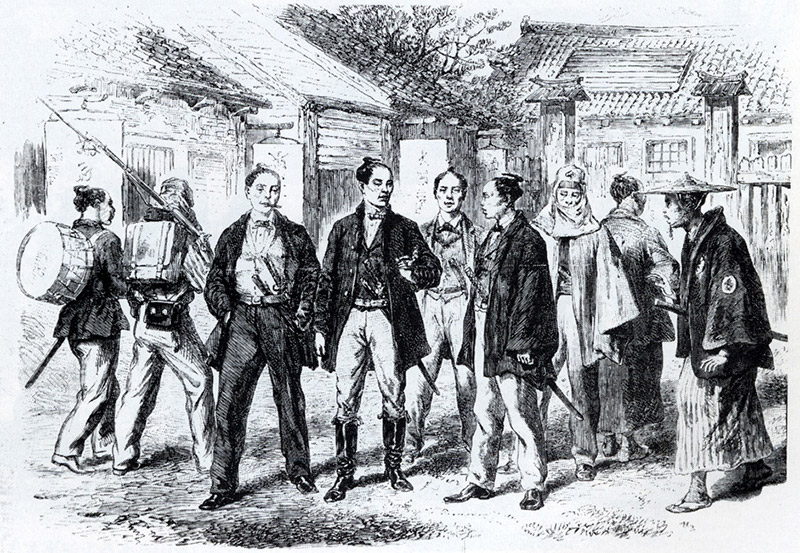

多年的孤立主義導致日本在技術和軍事實力方面落後於世界強國。 1850 年代初,當馬修·佩里準將展示其黑艦的軍事實力時,日本別無選擇,只能接受他的條件。用大野教授的話來說,接觸外國技術和文化的結果“粉碎了他們(日本)的自豪感”,使日本人認為自己的國家落後且與世界格格不入(43)。

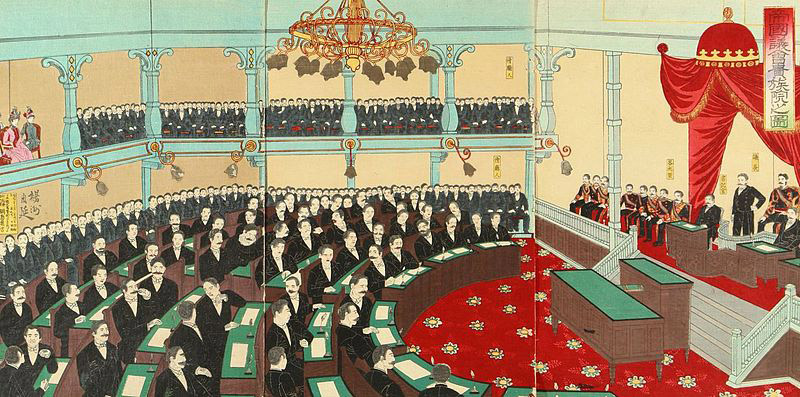

日本明治政府向西方看齊並不是為了西方化,而是為了成為世界舞台上的強國。雖然新渡戶鍾愛西方文化,但明治政府制定了三管齊下的現代化計劃,重點是「工業化(經濟現代化)、引入國家憲法和議會(政治現代化)以及對外擴張(軍事現代化)」(Ohno 18 ) 。

政治現代化將結束日本的封建制度,從而結束其統治的武士階級。新政策剝奪了武士的特權並模糊了階級劃分。世界歷史的航海解釋如下:

明治改革以中央政府控制下的地方縣取代了大名的封建領地。稅收集中化是為了鞏固政府的經濟控制……武士和平民之間所有舊有的區別都被抹去了:“武士放棄了他們的劍……非武士被允許有姓氏和騎馬。”武士家庭賴以生存的米津貼被微薄的現金津貼取代。許多前武士不得不面對尋找工作的屈辱。 (686)

同時,日本試圖透過加強軍事力量來保護自己的利益,並成為世界舞台上的一員。日本的努力很快就見效。 Kenichi Ohno 寫道:「在軍事領域,日本在1894-95 年贏得了對中國的戰爭,並開始入侵朝鮮(後來於1910 年成為殖民地)。日本也在1904-05 年與俄羅斯帝國進行了一場勝利的戰爭。這些勝利展示了日本不斷增長的軍事實力,並增強了該國所需的信心。對「西方國家」俄羅斯的勝利證明日本已成為世界強國。全世界都注意到了。

結束武士領導的封建制度帶來的階級流動和經濟自由刺激了日本的快速成長。明治政府的計劃已經開始有成果。

新渡戶別有用心

明治政府密謀加強日本在世界舞台上的影響力,而新渡戶則試圖從內部改變西方人對日本的看法。

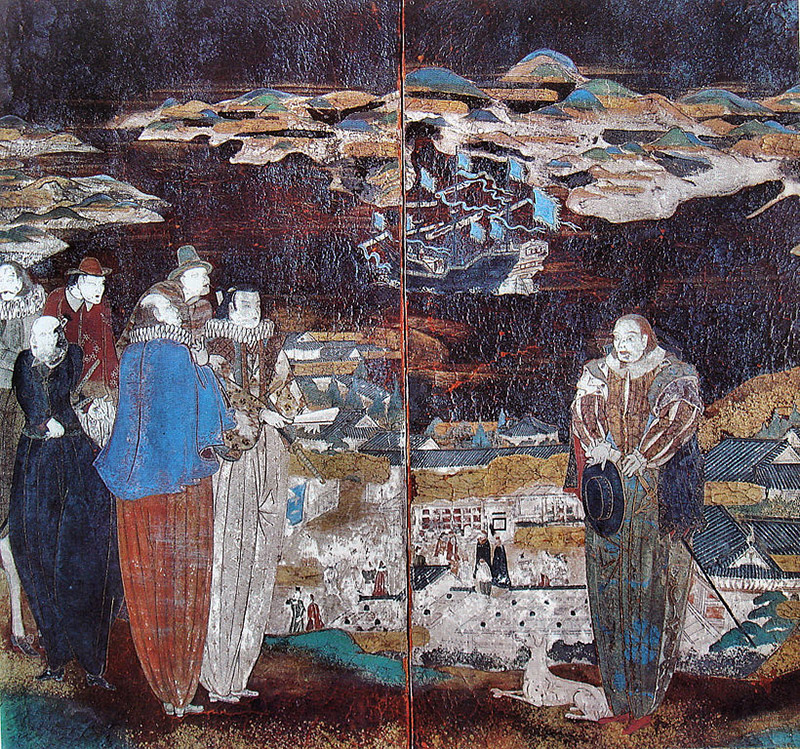

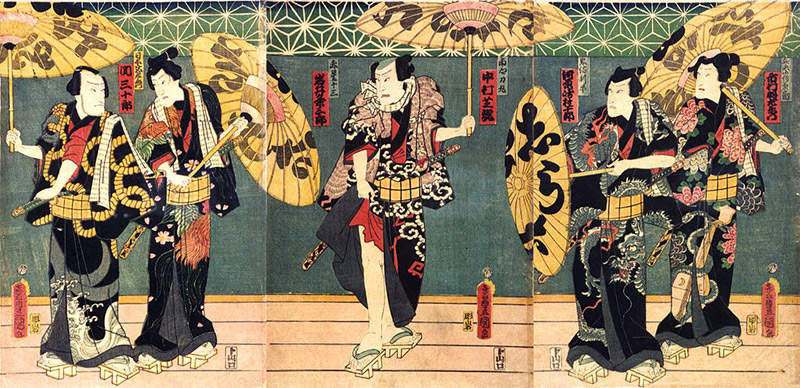

當時,西方人對這個以前與世隔絕的國家所知甚少。關於日本這個封建社會,軍隊依靠刀劍和弓箭的傳言將其描繪成一個樸素、古老的島國。利奧·布勞迪在《從騎士精神到恐怖主義》一書中寫道,「第一次世界大戰之前,許多歐洲人將日本視為一個武士社會,不受商業或文職政治家控制的影響,其貴族軍事階級仍完好無損」(467)。

新渡戶相信自己筆力的力量,開始寫作。透過將日本文化中最雄辯、最理想的面向簡化為西方可以理解的術語,他希望描繪出日本新的、高貴的形象。用英語寫作只會讓新渡戶的設計更加深思熟慮。瑪麗亞·納瓦羅和艾莉森·比比解釋說,

(新渡戶的書)的原文是用英語寫的,這不是新渡戶的母語……用外語寫作需要“過濾”自己的情感和表達方式……它可以讓作者對“新渡戶”表達更多的同理心。此外,為了讓作品更容易被目標讀者接受,人們會更意識到自己想要說什麼,或是希望避免說什麼。

1899 年,「自稱為日本與西方之間的橋樑」的新渡戶出版了後來成為他最著名的作品,這是對日本統治階級理想的浪漫化、西化的總結,即《武士道:日本的靈魂》(布勞迪467)。

基督教與武士的馴服

武士道:日本之魂代表了日本文化與西方意識形態的綜合。新渡戶將日本的武士階級與歐洲的騎士精神和基督教道德融合,從而馴服了日本的武士階級。 「我想表明…」新渡戶承認,「日本人(與西方人)並沒有那麼不同」(Benesch 165)。儘管《武士道:日本之魂》在武士滅亡多年後才上映,但它呈現了對武士階級的原始理想化和偶像化。

然而新渡戶圍繞著西方文化的原則塑造了武士道的概念,而不是像人們預期的那樣相反。《武士道:日本之魂》令人懷疑地缺乏對日本原始資料和歷史事實的參考。相反,英國文學的學生依賴西方作品和人物來解釋武士道的原則。新渡戶引用了腓特烈大帝、伯克、康斯坦丁·波別多諾采夫、莎士比亞、詹姆斯·漢密爾頓和俾斯麥等人的名言——這些資料與日本的歷史或文化沒有任何關係。

在他自稱的《日本靈魂》的闡述中,這位虔誠的基督徒更多地引用了西方聖經,而不是任何其他來源。不知何故,新渡戶認為聖經引用是對武士道的適當和令人滿意的支持。新渡戶宣稱:“日本人心中所宣揚和理解的(上帝)王國的種子,在武士道中開花結果。”

新渡戶在書中用大量篇幅將武士道歸因於基督教的教義。他引用《哥林多前書》313 章的禮貌,「恆久忍耐,有恩慈;不嫉妒,不自誇」(50)。新渡戶解釋說,武士道的仁慈「體現在基督教紅十字運動中,即對倒下的敵人的醫療救治中」(46)。

就連傳奇武士西鄉隆森的一句話也帶有聖經的光環。 「天愛我,也愛人,故以愛己,愛人」(78)。新渡戶本人承認,「其中一些說法讓我們想起了基督教的勸告,並向我們展示了自然宗教在實際道德方面可以在多大程度上接近啟示」(78)。

新渡戶甚至將武士描繪成日本的天賜祖先,塑造日本的神聖機制。 「日本之所以能成為日本,要歸功於武士。他們不僅是這個國家的花朵,也是這個國家的根。上帝所有的恩賜都流經了他們」(Nitobe 92)。

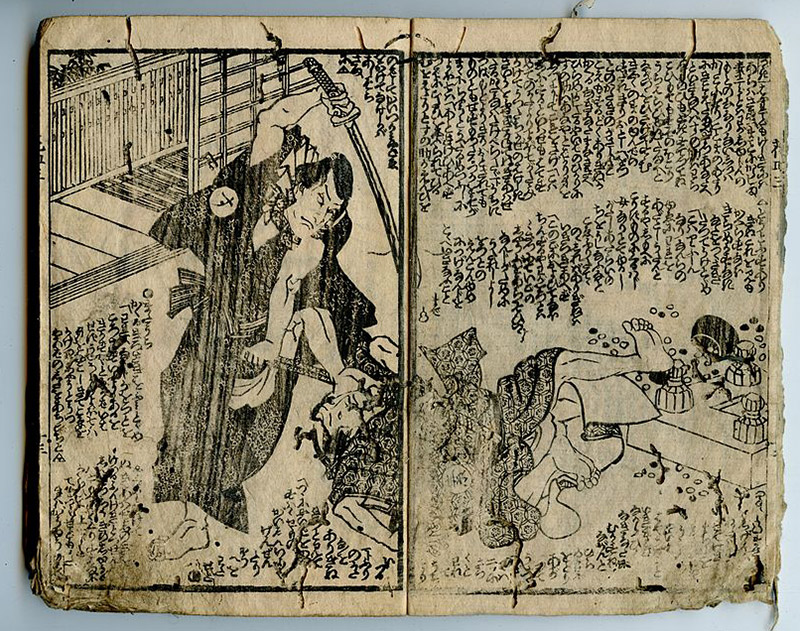

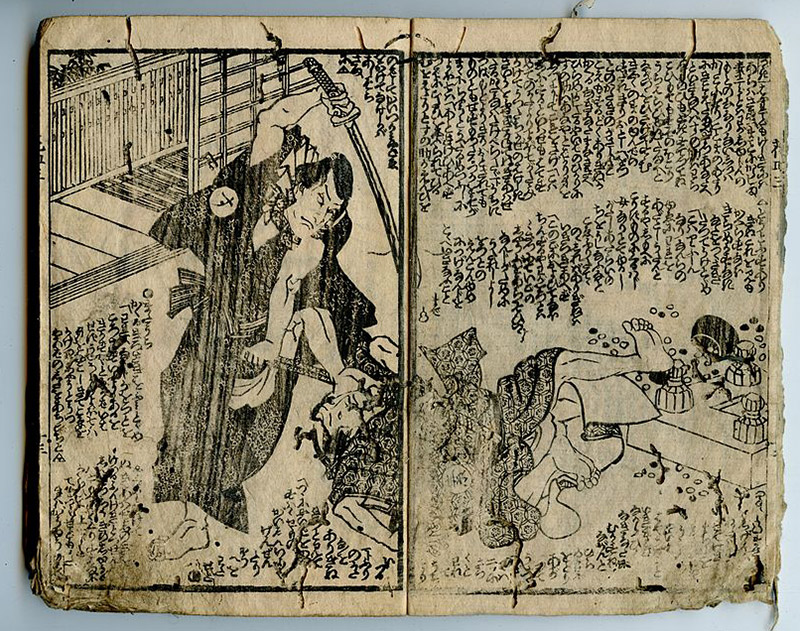

為自殺和劍賦予靈魂

在馴服武士的過程中,新渡戶甚至打著基督教習俗的幌子,為他們最野蠻的屬性——切腹(也稱為切腹或自殺儀式)和劍——辯護。而這一切都始於靈魂。

新渡戶宣稱,在西方和日本的習俗中,靈魂都住在胃裡。 「他們(《聖經》中的約瑟、大衛、以賽亞和耶利米)都贊同日本人中盛行的信仰,即靈魂被供奉在腹部」(113)。

這一斷言讓新渡戶將自殺提升為一種神聖的行為,“對榮譽的最高評價是許多人自殺的充分藉口”,然後挑戰西方讀者抵制他的解釋,“我敢說,許多優秀的基督徒,如果只有足夠誠實的人,才會承認對卡托、布魯圖斯、佩特羅尼烏斯和許多其他古代偉人結束自己塵世存在的崇高鎮定的著迷,即使不是積極的欽佩。 (113-114)。

劍也受到類似的待遇,新渡戶宣稱劍匠是藝術家,而不是工匠;劍不是武器,而是劍主人靈魂的代表。他解釋說:

擁有危險的工具本身就賦予了他(武士)一種自尊和責任的感覺和氣氛。 「他背負刀劍,不是徒然的」(羅 13:4)。他腰帶上的東西象徵著他的思想和心靈——忠誠和榮譽……在和平時期……它的用處就像主教佩戴的權杖或國王佩戴的權杖一樣(132 -133)。

新渡戶的熟練操作甚至使日本最「野蠻」的習俗變得尊嚴和崇敬。作者對基督教和西方文化的奉獻和了解使他能夠在歷史事實的幌子下打造出一種宣傳工具。新渡戶希望《武士道:日本之魂》能改變西方對日本的看法,提升日本在世界眼中的地位。

日本在西方接受的靈魂

《武士道:日本之魂》受到西方讀者的歡迎。蒂姆·克拉克在《武士道守則:武士的八種美德》中寫道,“這本薄薄的書後來成為一本國際暢銷書”,影響了那個時代一些最有影響力的人物。新托部的論文給泰迪·羅斯福留下了深刻的印象,以至於他「買了六十本與朋友分享」(Perez 280)。

儘管新渡戶幾乎只為學者閱讀,但他的影響卻滲透到了西方意識中。布勞迪寫道:「武士道的這種觀點對西方人來說是一個有吸引力的形象......鮑爾登·鮑威爾在他對童子軍的勸告中將武士道作為一種理想的榮譽準則。

新渡戶的敘事讓讀者得以一窺陌生、被誤解的世界,讓讀者感到震驚。在沒有任何反駁的情況下,西方讀者接受了《武士道:日本之魂》作為日本文化的事實代表,並且幾十年來它一直是西方關於該主題的典型作品。

日本的靈魂在日本的接待

《武士道:日本之魂》在日本得到了不同的反應。儘管武士道尚未進入日本的主流意識,但學者們對該概念的解釋各不相同,很少有人同意新渡戶的表述。事實上,「新渡戶表示,由於擔心讀者的想法,他多年來一直抵制他的書的日文翻譯」(Benesch 157)。許多讀者因其議程和不準確之處而攻擊新渡戶的作品。

奧列格·貝內施 (Oleg Benesch) 解釋說,大多數日本學者並沒有認真對待新渡戶的工作:

在初次出版時,新渡戶的《武士道:日本之魂》受到閱讀英文版的日本人的冷遇。津田宗吉在 1901 年寫了一篇嚴厲的批評文章,駁斥了新渡戶的中心論點。根據津田的說法……作者對他的主題知之甚少。新渡戶將武士道一詞與日本的靈魂等同起來是有缺陷的,因為武士道只能適用於單一階級……津田進一步批評新渡戶不區分歷史時期。 (155)

新渡戶的許多同時代人都認同以日本古代歷史為基礎的正統武士道。這種純粹的日本形式的武士道被視為獨特且優於任何外國意識形態。正統作家井上哲二郎甚至宣稱歐洲的騎士精神“只不過是女性崇拜”,甚至嘲笑儒家思想是低劣的中國進口(Benesch 179)。正統思想學派駁斥了新渡戶「腐敗的」、基督教化的武士道。

更複雜的是,在《武士道:日本之魂》上映時,很少日本人認識武士道這個詞。在《武藏:最後的武士之夢》中,押井衛解釋道:“武士道在日本人中並不為人所知……它出現在文學作品中,但並不是一個常用的詞。”

Benesch 支持 Oshii 的論點:

事实上,(《武士道:日本之魂》)只是现代日本第二部专门论述这一主题的长篇著作......数据库中只有四部作品在 1895 年之前提到过这一术语。 出版物的数量从 1899 年和 1900 年的总共三部增加到 1901 年的七部、1902 年的六部,从 1903 年起每年都有几十部。 (153)

新渡戶的著作早於武士道這個術語出現,因此對於潛在的日本讀者來說顯得陌生。

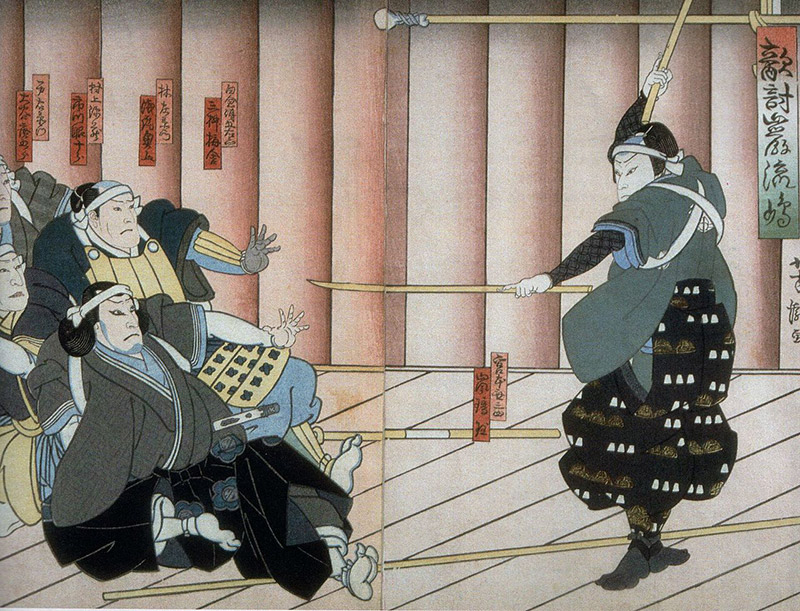

更糟的是,新渡戶的書將一種老式的、剝削性的階級制度浪漫化了,除了武士之外,每個人都希望拋棄這種制度。關於武士虐待下層階級的報道十分猖獗。雖然很少見,但武士可以合法地以「粗魯、無禮和不當行為」為由殺害下層階級成員(kirisutegomen )(坎尼格姆)。

由於存在如此不平等,下層階級對日本精英不感興趣也就不足為奇了。貝內什寫道,「大多數平民對武士的蔑視被描述為傳奇」(27)。與前階級結構的不平等和僵化相距不遠,普通民眾對崇拜或慶祝他們的前統治階級沒有興趣。

然而,新渡戶是為西方讀者寫作的,因此從未打算讓日本讀者閱讀《武士道:日本之魂》 。新渡戶用英語寫作,引用英語資料並將事實浪漫化,以滿足他的議程並影響西方思想。他並不指望擁有該主題批判知識的人會閱讀他的作品。 「我無意將《武士道:日本之魂》面向日本觀眾,」新渡戶承認(Benesch 165)。

對新渡戶稻造的批評

當《武士道:日本之魂》在日本受到嚴厲批評時,新渡戶「擔心(日本)讀者會怎麼想」被證明是正確的。然而,新渡戶很快就發現自己也受到了攻擊。許多日本學者指責作者沒有資格寫武士道,質疑他對日本歷史和文化的專業知識。

與那個時代的其他武士道理論家不同,新渡戶生活在他自己的國家和文化的郊區。他在北海道學習英語長大,遠離日本文化。新渡戶隨後移居國外,與一位美國女子結婚,並獻身於基督教。儘管他最終回到日本並擔任教授,但那是在武士道:日本之魂撰寫和出版之後很久。批評者聲稱,新渡戶與日本文化的疏離意味著他缺乏必要的歷史和文化知識來撰寫武士道這樣的日本固有主題。

新渡戶令人震驚地缺乏對日本歷史和文學的參考,這增加了這個論點的分量。奇怪的是,《武士道:日本之魂》仍然缺乏事實支持,成為新渡戶模稜兩可的閒聊和對想像中的過去的嚮往的載體。

新渡戶在日本的引用中為數不多,讓人對他的誠信產生了質疑。例如,儘管西鄉隆盛實際上領導了薩摩叛亂,但英雄動機和自殺新渡戶的提及被美化,以將西鄉視為理想的武士。

公平地說,新渡戶的許多批評者也忽略了事實歷史,並挑選數據來解釋他們自己對武士道的解釋。

即使在 20 世紀,許多武士道作家也傾向於提出自己的理論,而不參考或考慮其他評論家對這個主題的想法。相反,他們逐漸依靠精心挑選的歷史資料和敘述來支持他們的理論。 (貝尼施 116)

然而,新渡戶同時代人的行為並不能成為他自己的行為的藉口。《武士道:日本之魂》的核心內容是毫無根據的猜想,同時揭露了作者對日本歷史和文化的脫離。新渡戶放棄了事實,同時對他不支持也不可能支持的歷史進行了古怪的漫無目的的胡言亂語。新渡戶在宣揚普世道德以贏得西方國家青睞的同時,卻未能證明武士道的真實存在。

給我那個新的舊式武士道嗎?

流行文化將武士道視為一種具體的道德準則,與日本神聖的武士階級緊密相連,以至於兩者似乎密不可分。但實際上武士道一詞直到二十世紀才出現。事實上,新渡戶是最早擁抱武士道的學者之一,他認為這個詞是他在 1900 年創造的。

「像「budo」(武術之道)、「bushi no michi」(武士之道)和「yumiya no michi」(弓箭之道)這樣的術語更為常見,」Benesch 寫道 (7)。儘管這些術語證明武士理想在日本人的意識中佔有一席之地,但將它們等同於武士道是不準確的。

武士道這個概念在明治時代開始使用,但直到明治末期才被廣泛認可。儘管有流行的形象,古代武士並沒有寫下或討論武士道。正如浪漫化的歷史讓我們相信的那樣,不光彩的行為並沒有結束職業生涯和生命。

這並不是說古代日本缺乏法律或道德準則——這樣的說法是荒謬的。羅莎琳德·懷斯曼(Rosalind Wiseman)在她的《蜂王和崇拜者》一書中說得最好,「我們都知道什麼是榮譽準則。這是一套行為標準,包括紀律、品格、公平和忠誠,供人們堅持和實踐」(Wiseman 191 )。從工作場所和俱樂部等小型社區到宗教和國家等大型機構,每個文化都有榮譽準則和道德觀念。

但武士道、武士和古代日本的流行表述描繪了明確且嚴格執行的榮譽準則。羞辱自己就是精神和肉體的自殺。武士階級消亡後,諸如《武士道:日本之魂》和山本常友的《葉隱》等書籍開始流行,這有助於促進這一神話,使武士看起來似乎是按照一套字面上的、明確定義的規則生活和行事,而這些規則從未存在過。

一些研究人員引用了kakun 家訓,或稱家庭家規,為武士道的起源。 「在許多情況下,家訓旨在充當作家的兒子或繼承人的道德和行為準則,並且經常反映對氏族繁榮和連續性的擔憂」(亨利·史密斯)。

大多數研究人員都沒有將家庭家訓歸因於整體道德準則。 Benesch 評論道,「戰後關於中世紀家庭法典的學術研究很少或根本沒有提到武士道……有證據表明,武士道與家訓(kakun)的聯繫是明治時代晚期解釋的產物」(8)。代代相傳的家訓因家族而異。這些捲軸成為了傳家寶,而不是一套生活規則。

關於這個主題的早期討論暴露了武士階級價值觀是多麼模糊。 「對與武士道德有關的原始資料和後來的學術研究並沒有揭示出在前現代日本歷史的任何時候都存在單一的、廣泛接受的、武士特定的道德體系」(Benesch 14)。此外,戰士們專注於勝利和生存——戰鬥並不適合適得其反的榮譽準則。

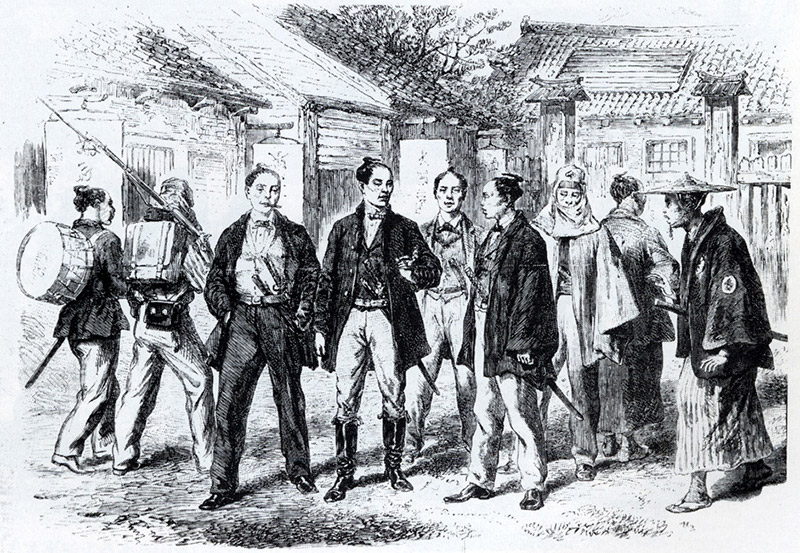

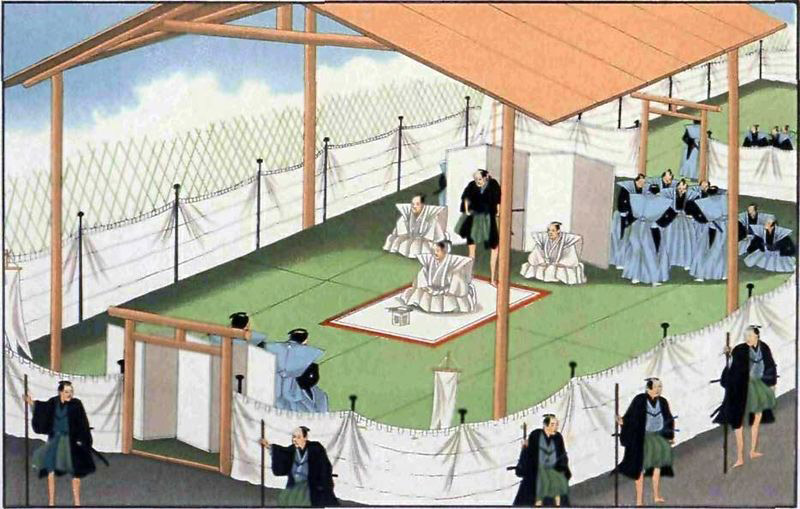

江戶時代製定的任何法律或道德準則實際上都是為了馴服日本野蠻、無原則的武士階層,因為他們從戰場轉向辦公室工作。

「武士在早期幾個世紀都忙於戰鬥,直到相對和平的江戶時代才開始關注道德」(15)。

由於沒有戰爭可打,德川政府將刀劍降級為階級裝飾品,成為最終的地位象徵。

武士成為上流官僚,有閒暇時間進行哲學追求。

榮譽和禮節的觀念對不忠和毫無意義的暴力不屑一顧,這符合德川政府維持對統一日本的控制的戰略。

尊敬的武士:事實還是虛構?

在古代日本,武士道從來沒有像「武士道:日本之魂」所暗示的那樣作為一種榮譽準則或術語存在。新渡戶對武士階級的描繪證明了自己同樣是做作的。像所有人類一樣,武士的道德因人而異。

尊敬的戰士?

歷史記載表明,武士不遵循榮譽準則,這對生存、勝利和舒適的生活來說是一個不切實際的障礙。蒂蒙·斯克里奇寫道:「我們談論的是神話。武士曾經戰鬥至死的信念經不起調查,也沒有在需要贖罪時做出剖腹犧牲的說法。武士之道就是死亡的座右銘很早就被發明了。 ”當死亡不再出現在大多數武士的腦海中或成為他們生活中的現實之後……他們是官僚。”

儘管切腹被描述為常見做法,但它並不是新渡戶所描述的武士的中流砥柱。

「太痛了,」新渡戶解釋道。 “自殺實際上是假裝用木劍甚至紙扇刺傷,然後由發出信號的助手從後面乾淨利落、無痛地砍下頭部。”

貝內什寫道,切腹自殺「僅限於絕望的情況,在這種情況下,戰敗的戰士肯定會受到酷刑,這在當時是一種常見的做法」(16)。

作家們忽略了切腹的真實歷史,將這種做法浪漫化,並將其提升為終極的榮譽形式。

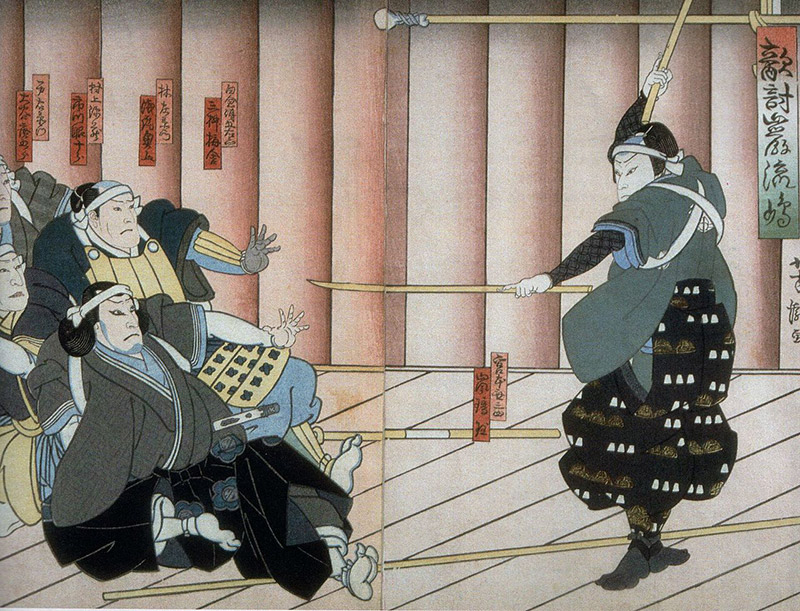

那麼所謂武士之魂的劍呢?查爾斯·沙拉姆(Charles Sharam) 解釋說:「在[德川時代]之前,武士實際上是弓箭手,他們精通弓箭,必要時偶爾會使用其他武器。在他們的歷史的大部分時間裡,劍並不是一種武器。

在現代媒體中,槍被描述為劍的對立面,代表著對「武士價值觀」的放棄。響亮的外國武器體現了一種響亮、骯髒(字面意思是火藥和煙霧)、不光彩的遠距離殺戮方式。但武士最初選擇的武器──射箭呢?雖然弓很優雅,但它可以發射彈丸並從遠處殺死——就像火器一樣。射箭不應該像槍一樣被視為不光彩的嗎?

此外,武士還擁有騎馬作戰的特權和優勢。事實上,押井認為宮本武藏創造了他傳奇的二天一 兩天一,或兩種劍術,以獲得更好的平衡和更有效的從馬鞍上殺戮。從有利的騎乘位置射擊和砍倒步兵,都與現代武士形像中流行的地面劍士的光榮形象相衝突。

新渡戶在《武士道:日本之魂》中將忠誠描述為武士階級的光輝特質。然而,武士的不忠行為玷污了日本歷史。 G. 卡梅倫‧赫斯特三世寫道:

事實上,前現代時代最令人不安的問題之一是…勸告武士實踐忠誠的準則與折磨中世紀日本武士生活的常見不忠事件之間的明顯差異。毫不誇張地說,中世紀日本最關鍵的戰役是由戰敗將軍的一個或多個主要封臣的叛逃(即不忠)決定的。 (517)

儘管武士道譴責唯物主義是一種腐敗力量,但武士並不是像新渡戶這樣的武士道作家所描述的反唯物主義的縮影。貝內什解釋:

忠誠需要付費。在這個過程的每個階段都期望互惠……大多數武士會認為自己的生命比上級的生命重要得多……(此外)對京都的反复搶劫證明了缺乏道德,以及武士的重要性在外觀上(代表)與樸素節儉的武士的流行形象形成鮮明對比。 (19-21)

尊貴的生活方式?

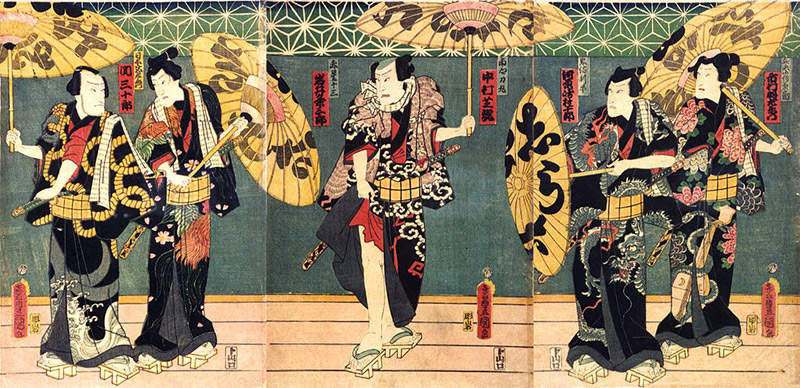

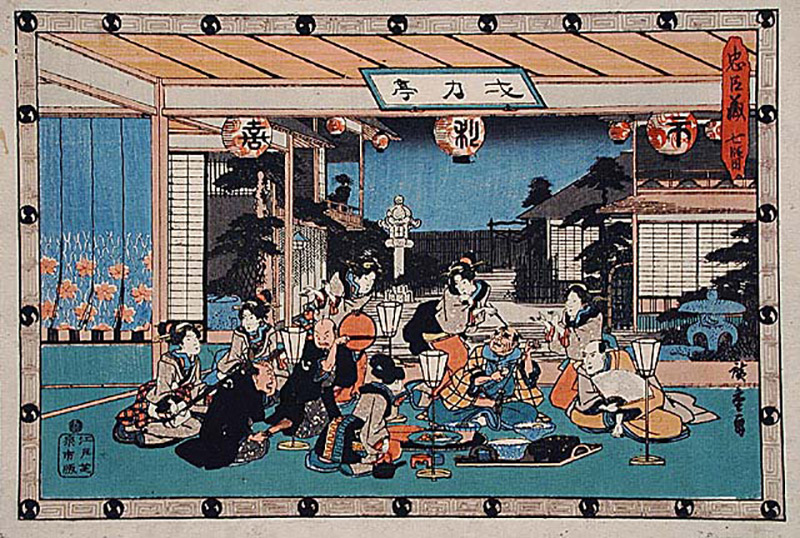

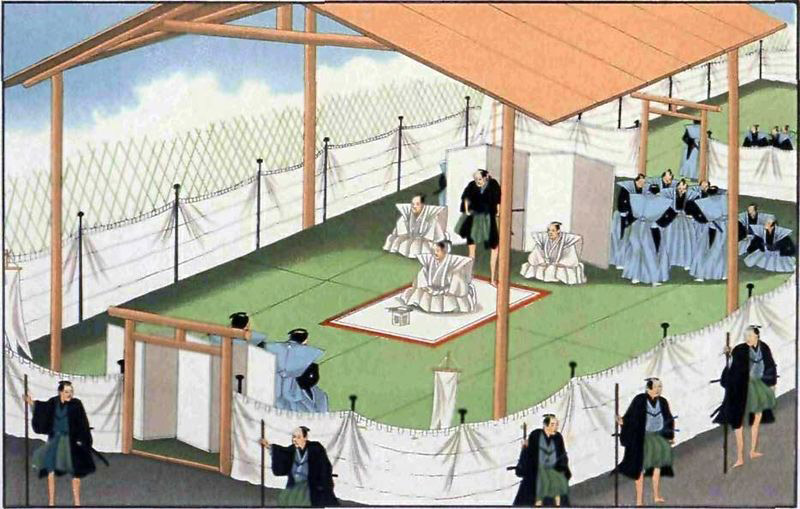

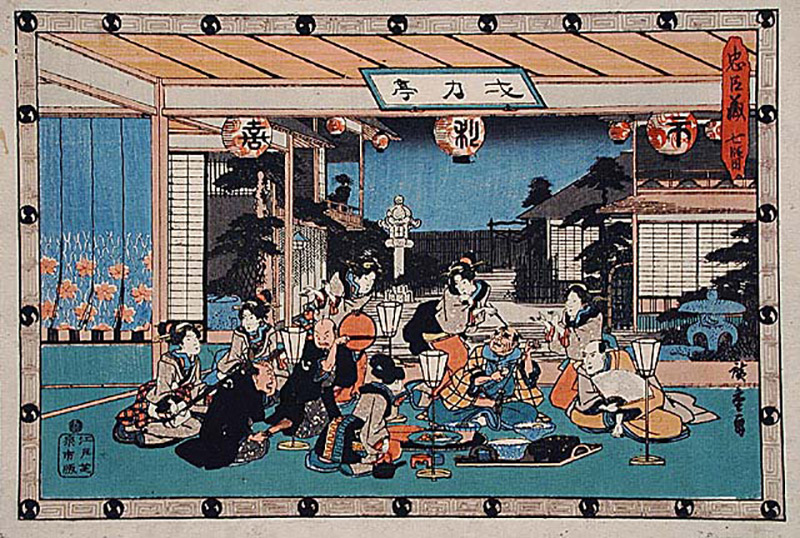

德川開創了前所未有的和平時代,永遠改變了日本武士階級的生活。許多武士從戰場轉到公務員職位。作為社會上層階級,這些武士在新時代的官僚機構中佔據著舒適的職位。劍成為地位的象徵,而不是戰鬥。閒暇時間充裕,這些武士有茶道、書法等嗜好。其他人則在遊樂區消磨時光。

當農民在田裡辛苦工作以養活國家並納稅,商人努力維持在社會上受人尊敬的地位時,武士則從事案頭工作以獲得大米津貼。可支配收入為武士提供了物質主義的奢侈,前武士成為日本最時尚的階級。換句話說,武士代表了德川時代的「百分之一」(根據唐·坎寧安的說法,實際上是百分之六到百分之八)。

但並非所有武士都享受上流社會的生活。地位低下的武士只能領取微薄的津貼,勉強維持日常生活。受德川時代禁止外來失業的嚴格法律的約束,其中一些武士放棄了自己的地位,成為工匠或農民(坎寧安)。

還有一些德川時代的武士找不到工作。這些流浪漢常常做出不光彩的行為。正如唐·坎寧安 (Don Cunningham ) 在《大鳳術:武士時代的法律與秩序》中所解釋的那樣,「面對失業和新社會中不明確的角色,許多武士訴諸犯罪活動、不服從與反抗」(坎寧安)。這些武士前途渺茫,挫折感不斷增加,衣著華麗,言辭浮誇,騷擾下層階級,加入幫派,在街上打架。

無論是精英公務員還是失業的惡棍,德川時代的武士幾乎沒有強化新渡戶對榮譽階層的描述,為其他階層樹立了崇高的道德標準。

尊貴的解釋?

明治政府帶來的地位喪失並沒有讓那些習慣了德川體制的武士感到高興。 Benesch 指出,「武士發現他們的社會地位越來越受到經濟實力雄厚的平民的挑戰,其中一些也購買或接受武士特權,例如佩戴劍的權利」(24)。在和平時代,連刀劍、「靈魂」和武士的象徵都變得毫無用處,也失去了意義。新階級的流動性使得傲慢的下層階級能夠在財富和地位上挑戰武士。

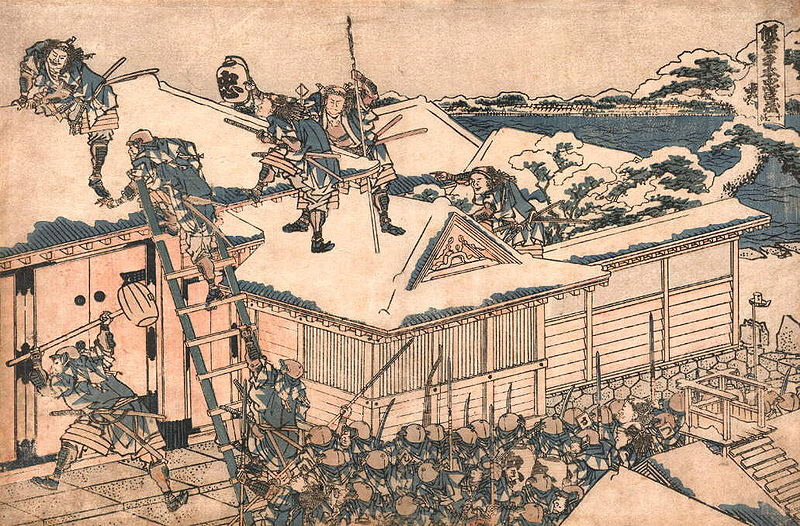

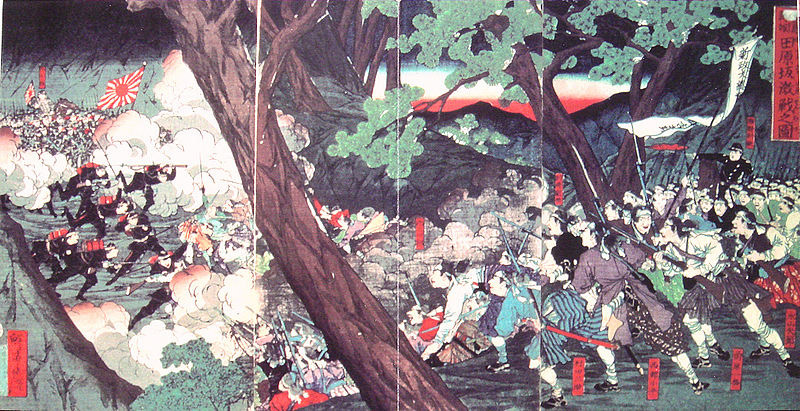

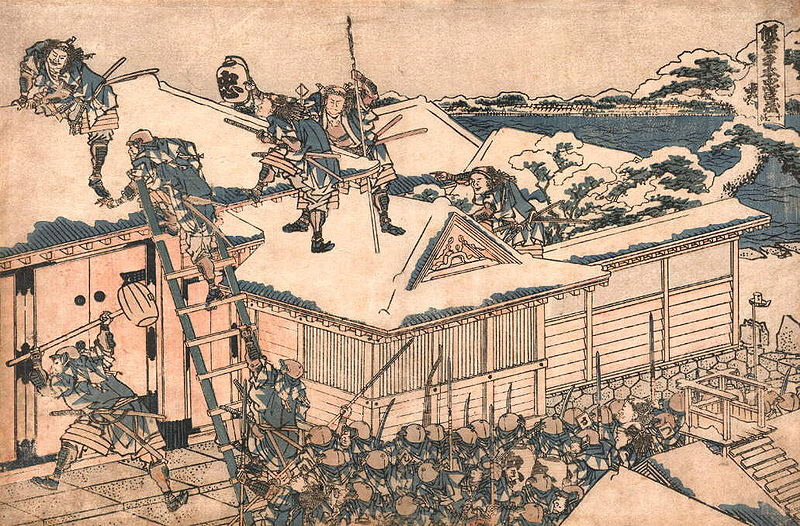

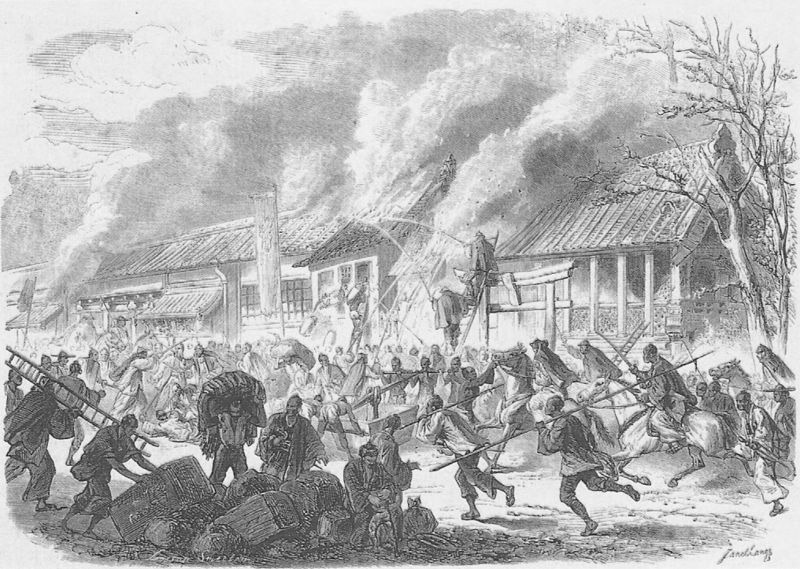

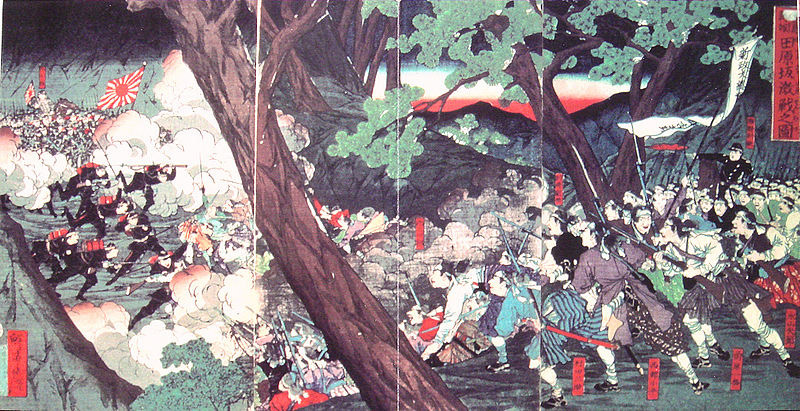

1877 年的薩摩之亂證明,這些變化促使一些武士採取了行動。 「逐漸取消他們的津貼和特殊地位……產生了一大群心懷不滿的士族(武士),其中一些人聚集在西鄉隆森周圍,煽動叛亂。”

《武士道:日本之魂》和《最後的武士》等浪漫化歷史將西鄉描繪成真理、榮譽和武士準則純潔性的捍衛者。事實上,過去時代的頑固分子進行了反抗,試圖維持自己的地位和舒適的生活方式,包括大米津貼、財產和裙帶關係。大野教授指出:

以前的武士階層,現在被剝奪了大米工資……對年輕武士建立的新政府特別不滿……諷刺的是,絲綢和茶葉找到了巨大的市場,飛漲的價格使農民富裕起來。富裕的農民購買了西式服裝。商人階級不斷壯大,尤其是在橫濱……通貨膨脹飆升,武士和城市人口遭受苦難。 (41-43)

低階武士和失業武士中的許多人都在推動變革,他們認為明治時代是更好的變化。階級結構的削弱意味著貧窮或失業的武士可以到其他地方尋求財富。世襲制度的廢除使得流動性得以實現。突然間,那些身居高位的人找到了努力工作的動力。儘管西鄉和其他頂級武士是少數,但損失最大並因此叛亂。

對新渡戶來說幸運的是,榮譽是情人眼裡出西施,這是可以解釋的概念。例如,新渡戶將《47浪人物語》視為忠誠的終極例子,但其他人卻將其解讀為懦弱的偷襲。日本將宮本武藏視為最熟練的劍士,但他在決鬥中遲到並「不光彩地」偷襲對手。新渡戶將薩摩之戰描述為一場榮譽之戰,而不是一場為維護階級地位而驅動的叛亂。

儘管新渡戶和他的作家同行們哀嘆現代性對武士道的腐敗和破壞,但這個概念從來沒有像他們所描述的那樣存在。武士並不是他們所代表的忠誠、光榮的武士道堡壘。查爾斯‧沙拉姆 (Charles Sharam) 在《武士:神話與現實》一書中寫道,「武士是日本文明的多餘負擔……他們對社會貢獻甚少,卻消耗了大量財富。也就是說,他們在明治維新時期的消除是絕對有必要的。

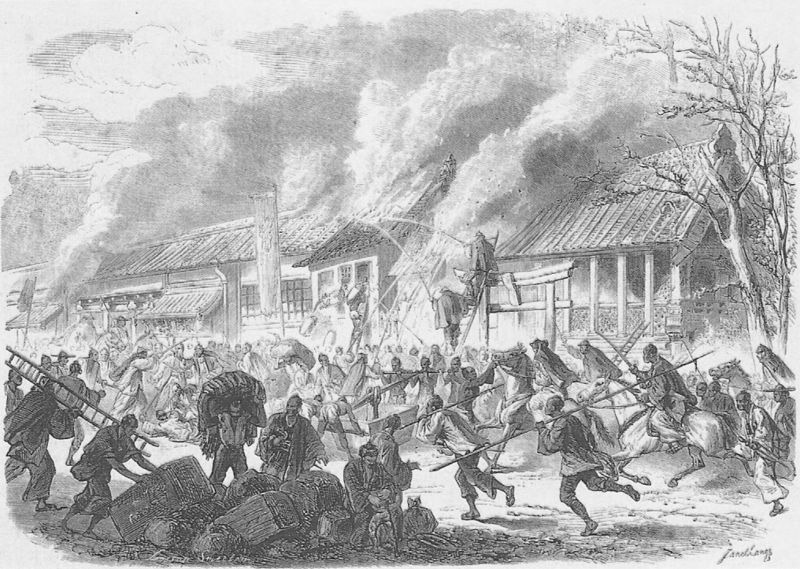

法西斯主義-新托部的意外後果

驅逐武士僅僅幾十年後,日本政府就為其前統治階級找到了新的用途。儘管在海外取得了軍事勝利,日本官員仍感到軍隊缺乏信心和鬥志。武士道的光榮武士戰鬥至死的形象提供了解決方案(押井)。改變西方對日本看法的意識形態現在將助長法西斯主義和日本戰爭機器。

新渡戶認為,日本有著悠久的光榮、勇敢和能幹的武士血統,這些武士可以擴展到各個階級。他寫道,「武士道以多種方式從其起源的社會階級中滲透下來,並在群眾中發揮作用,為全民提供了道德標準」(新渡戶)。

武士道的傳承意味著即使是最卑微的公民也可以渴望並獲得武士的榮耀和榮譽。武士精神在日本人的靈魂中根深蒂固。透過將武士道納入主流,日本政府希望透過在軍隊和公民中應用這種意識形態來增強士兵和公民的信心。

此外,武士道透過展示日本相對於其他國家的道德和文化優越性,為日本的帝國主義事業辯護。武士道作家鈴木千樂「認為西方和中國思想對日本來說都是陌生的,國家必須關注自己的『真正精神』並弘揚『民族精神主義』」(Benesch 101)。就像美國的天定命運和推動十字軍東徵的宗教狂熱一樣,浪漫化的武士道有助於激勵日本的帝國主義議程並使之合理化。

既然已經找到了一種意識形態,日本政府就必須讓武士道「在群眾中發酵」或進行動人的宣傳。 「文明啟蒙」、「富國強軍」成為戰時口號。國有化的教育體系簡化了課程,以傳播政府言論並培養開明、做好戰鬥準備的公民。

國家課程改變了歷史以適應政府議程。 「江戶時代的文本對德川時代之前的狀況表現出最大的懷舊之情,經過精心挑選、濃縮和編輯,以清除其中那些與二十世紀初國家計劃背道而馳的元素」(Benesch 21)。

強制性文本將過去的事件和人物浪漫化。押井表示,“虛假圖像是出於政府的需要而製作的。”由於政府的議程,武士道、葉隱和宮本武藏等不熟悉的實體進入了主流意識。

新渡戶的《武士道:日本之魂》因其意識形態和過去的浪漫主義而在戰前的日本廣受歡迎。新渡戶宣稱,「大和魂,日本的靈魂,最終表達了島國的民族精神」(27)。希特勒將民族精神定義為人民精神,以實現他自己的法西斯議程(Griffen 255)。與武士道一樣,民族精神慶祝其國家的民間歷史、文化遺產和種族。這些對過去不切實際的懷念播下了法西斯主義的種子,導致了二戰期間難以言喻的暴力和悲劇。

武士道的最終體現是神風特攻隊飛行員和步兵,他們「光榮」地為國家犧牲了自己。英國廣播公司 (BBC)的戴維·鮑爾斯 (David Powers) 寫道:“雖然一些日本人被俘,但大多數人都在戰鬥,直到被殺或自殺。”正如這些士兵政府發行的《葉隱》卷所教導的那樣,“只有做好隨時赴死的準備的武士才能完全獻身於他的主人。”

新渡戶的遺產

新渡戶對日本過去的幻想理想化雖然從未有意為之,但卻有著明顯的法西斯意涵。《武士道:日本之魂》對即將發生的事情做出了怪異的預測,

自我控制的紀律很容易走得太遠。它能夠很好地壓制靈魂的和藹電流。它可以迫使順從的本性變得扭曲和怪物。它可能會產生偏執,滋生虛偽,或習慣性的感情。 (110)

新渡戶和帝國主義政府都扭曲事實,利用日本的歷史來達到自己不可告人的目的。感謝新渡戶,日本古代的士兵和官僚成為了光榮的精神戰士。武士更關心忠誠、仁慈、禮儀和自我控制,而不是勝利、金錢利益或社會地位,成為讀者嚮往的典範。

但歷史是不斷變化的。真實的事件從記憶中消失,多年的解釋,無論是有意或無意,塑造了現代人對過去的理解。事實、觀點和幻想的模糊混合體進入主流意識,並被視為「真實」歷史。

薩摩之亂末期西鄉隆盛真的切腹自殺了嗎?戴維·克羅克特真的在阿拉莫戰鬥至死,還是像一些歷史學家認為的那樣,他是在投降後被處決的?薩摩之戰是一場德行之戰還是地位之戰?波士頓茶黨是對不公平稅收的反抗,還是美國富商為維持茶葉壟斷而奮鬥的反抗?那麼喬治華盛頓砍倒他父親的櫻桃樹又如何呢?還有他的木牙?

雖然真相可能永遠不會為人所知或達成共識,但質疑我們所謂的歷史背後的事件和動機很重要。就日本而言,政府操縱歷史,包括美化的武士階級和武士道準則,成為有助於激發狂熱戰爭機器的宣傳。

社會經常在過去尋找我們當前問題的答案。就像當前的茶黨運動對美國過去的錯誤利用一樣,新渡戶的武士道引發了人們對過去時代未經證實的簡單和純潔的嚮往。

正如《最後的武士》所證明的那樣,新渡戶的遺產將繼續存在。無論準確與否,他對武士道和武士的簡化理想化仍然贏得了全世界的欽佩。只要這種情況持續下去,流行文化就會追隨新渡部稻造和日本政府的腳步,利用他們的神話形象來達到自己的目的──消費者辛苦賺來的錢。

Bushido: Way of Total BullshitEverything Tom Cruise taught you about samurai is wrong

• 6322 words written by Rich • Art by Aya Francisco

The term bushido calls forth ghosts of Japan's hallowed samurai class. A class so bent on preserving honor, they'd rather slit their own bellies in ritualistic suicide than live a shamed existence.

In The Last Samurai, bushido melds with Nathan Algren's soul, curing the troubled American of alcoholism, war trauma, and self-loathing. What powerful medicine! A reinvigorated, purified Algren turns his back on his employers to join rebel samurai bent on defending bushido, their dignified honor-code of loyalty, benevolence, etiquette, and self-control.

At least, that's what popular culture would have us believe. In reality the term bushido went unrecognized until the early twentieth century, long after Nathan Algren's fictitious character joined the factual Satsuma Rebellion and years after the ousting of the samurai class. In all likelihood samurai never even uttered the word.

It may come as an even greater surprise that bushido once received more recognition abroad than in Japan. In 1900 writer Inazo Nitobe's published Bushido: The Soul of Japan in English, for the Western audience. Nitobe subverted fact for an idealized imagining of Japan's culture and past, infusing Japan's samurai class with Christian values in hopes of shaping Western interpretations of his country.

Though initially rejected in Japan, Nitobe's ideology would be embraced by a government driven war machine. Thanks to its empowering vision of the past, the extreme nationalist movement embraced bushido, exploiting The Soul of Japan to pave Japan's way to fascism in the buildup to World War II.

And so too The Last Samurai exploits Inazo Nitobe's depiction of bushido, renewing movie-going audiences' admiration for a venerable concept and glorified past that never truly existed. But as bushido's precarious history proves, the truth often takes a back seat to more fashionable depictions, whether it be to change Western perceptions, fuel a fascist war agenda, or sell movie tickets.

Inazo Nitobe

Born in 1862 in Iwate Prefecture, Inazo Nitobe was just a baby when the final remnants of Japan's ruling samurai class came to an end. Despite being of the samurai class themselves, Nitobe's family remained far removed from the battlefields and warrior culture of old Japan, gaining recognition as pioneers of irrigation and farming techniques.

At age nine Nitobe moved to Tokyo to live with his uncle where he began intensive English study. A unique subject of study at the time, Nitobe would become fluent in the language. In Death, Honor, and Loyalty: The Bushido Ideal, Cameron Hurst writes, "The Christian son of a late Tokugawa samurai… who was educated largely in English at special schools early in the Meiji era, Nitobe… could communicate with foreigners to a degree that even the most ardent exponents of kokusaika (internationalization) today would envy" (511).

In 1877 Nitobe made his way to Hokkaido where he enrolled in Sapporo Agricultural College. Created under the influence of William S. Clark, a devout Calvinist from New England, the school served to further solidify Nitobe's commitment to the Christian faith and he joined Clark's own "Sapporo Band" of Christians (Oshiro).

In Sapporo, Nitobe's estrangement from the Japanese society, culture and people grew. Japan's northernmost island remained largely unsettled wilderness and shared few cultural connections with mainland Japan. "Hokkaido was only just becoming a real part of Japan," Hurst writes, "so Nitobe was essentially isolated spatially, culturally, religiously, and even linguistically from the currents of Meiji Japan" (512).

Following his graduation from Sapporo Agricultural College, Nitobe began graduate school in Tokyo. Unsatisfied with his studies, in 1884 Nitobe moved to the United States and enrolled in John Hopkins University. After graduating, the globetrotting Nitobe would bounce around Germany, the United States and Sapporo and even become the under-secretary general of the League of Nations (Samuel Snipes).

Unique to his era, Nitobe's knowledge of English and Western literature remains impressive even by today's standards. Oleg Benesch, author of the in-depth study Bushido: The Creation of a Martial Ethic In Late Meiji Japan writes that Nitobe grew to be "more comfortable in English than Japanese" and eventually "lamented his lack of education in Japanese history and religion" (159).

It was during his time in California that Nitobe penned Bushido: The Soul of Japan. The contrived imagining of the samurai class reshaped Western perceptions of Japan and would eventually come to redefine Japan's own interpretation of bushido and the samurai class.

Playing Catch-Up: The Meji Restoration

While Nitobe immersed himself in Western religion and culture, the Japanese government continued its own international pursuit – modernization. Professor Kenichi Ohno of GRIPS explains, "The top national priority was to catch up with the West in every aspect of civilization, i.e. to become a 'first-class nation' as quickly as possible" (43).

Years of isolationism meant Japan had fallen behind the world powers in terms of technology and military power. When Commodore Matthew Perry flexed his black ships' military muscle in the early 1850s, Japan had no alternative but to accept his terms. In professor Ohno's words, resulting exposure to foreign technology and culture "shattered their (Japan's) pride," making Japanese view their own nation as backward and out of step with the world (43).

Japan's Meiji government looked to the West not to Westernize per se, but to become a powerful nation on the world stage. While Nitobe doted over Western culture, the Meiji government devised a three pronged plan for modernization that focused on "industrialization (economic modernization), introducing a national constitution and parliament (political modernization), and external expansion (military modernization)" (Ohno 18).

Political modernization would bring an end to Japan's feudal system and therefore its ruling samurai class. New policies stripped the samurai of privileges and blurred class separation. Voyages in World History explains:

The Meji reforms replaced the feudal domains of daimyo with regional prefectures under control of the central government. Tax collection was centralized to solidify the government's economic control… All the old distinctions between samurai and commoners were erased: 'The samurai abandoned their swords… and non-samurai were allowed to have surnames and ride horses.' The rice allowances on which samurai families had lived were replaced by modest cash stipends. Many former samurai had to face the indignity of looking for work. (686)

Meanwhile, by strengthening its military Japan sought to protect its interests and become a player on the world stage. And Japan's efforts saw quick results. Kenichi Ohno writes, "In the military arena, Japan won a war against China in 1894-95 and began to invade Korea (it was later colonized in 1910). Japan also fought a victorious war with the Russian Empire in 1904-05." These victories demonstrated Japan's growing military might and gave the nation a needed confidence boost. Victory over Russia, a "Western nation," proved Japan had become global power. The world took notice.

Class mobility and economic freedoms ushered in by ending the samurai led feudal system spurred Japan's furious growth. The Meiji government's plans had begun to bear fruit.

Nitobe's Ulterior Motives

While the Meiji government plotted to strengthen Japan's presence on the world stage, Nitobe sought to change Westerners' perceptions of Japan from within.

At the time, Westerners knew little about the formerly isolated nation. Rumors about Japan – a feudalistic society whose armies relied on swords and bows and arrows – painted the picture of an unsophisticated, archaic island nation. In From Chivalry to Terrorism Leo Braudy writes, "Before World War I, many in Europe viewed Japan as a warrior society unadulterated by either commerce or the control of civilian politicians, with it's aristocratic military class still intact" (467).

Nitobe put faith in the power of his pen and began to write. By simplifying the most eloquent, ideal aspects of Japanese culture into terms the West could relate to, he hoped to paint a new, noble image of Japan. Writing in English only served to make Nitobe's contrivance more deliberate. Maria Navarro and Alison Beeby explain,

The original text (of Nitobe's book) was written in English, which was not Nitobe's mother tongue… Writing in a foreign language obliges one to "filter" one's own emotions and modes of expression… It allows the writer to express more empathy for the 'other culture' (in Nitobe's case Western culture). Furthermore, one is much more conscious of what one wants to say, or what one wishes to avoid saying, in order to make the work more acceptable for intended readers.

In 1899 Nitobe, "the self-described bridge between Japan and the West" published what would later become his most famous work, a romanticized, Westernized summation of the ideals of Japan's governing class, Bushido: The Soul of Japan (Braudy 467).

Christianity and the Taming of the Samurai

Bushido: The Soul of Japan represents a synthesis of Japanese culture with Western ideology. Nitobe tames Japan's samurai class by fusing it with European chivalry and Christian morality. "I wanted to show…" Nitobe admitted, "that the Japanese are not really so different (from people of the West)" (Benesch 165). Although it saw release years after the extinction of the samurai, Bushido: The Soul of Japan presents an original idealization and idolization of the samurai class.

Yet Nitobe shapes the concept of bushido around principles of Western culture, not the other way around as might be expected. Bushido: The Soul of Japan offers a suspicious lack of references to Japanese source material and historical fact. Instead, the student of English literature relies on Western works and personalities to explain the bushido's principals. Nitobe quotes the likes of Frederick the Great, Burke, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, Shakespeare, James Hamilton and Bismarck – sources that have no connection to Japan's history or culture.

In his self-proclaimed formulation of The Soul of Japan, the devout Christian references the Western Bible more than any other sources. Somehow Nitobe sees Bible quotes as appropriate and satisfactory support for bushido. "The seeds of the Kingdom (of God) as vouched for and apprehended by the Japanese mind," Nitobe declares, "blossomed in Bushido."

Nitobe spends much of the book ascribing bushido to the tenets of Christianity. Politeness, he quotes Corinthians 313, "suffereth long, and is kind; envieth not, vaunteth not itself" (50). Bushido's benevolence, Nitobe explains, is "embodied by the Christian Red Cross movement, the medical treatment of a fallen foe (46)."

Even a quote by Saigo Takamori, the legendary samurai, takes on a Biblical aura. "Heaven loves me and others with equal love; therefore with the love wherewith though lovest thyself, love others" (78). Nitobe himself admits, "Some of those sayings reminds us of Christian expostulations, and show us how far in practical morality natural religion can approach the revealed" (78).

Nitobe even goes as far as to paint the samurai as Japan's heavenly sent forefathers, holy mechanisms that shaped Japan. "What Japan was she owed to the samurai. They were not only the flower of the nation, but its root as well. All the gracious gifts of Heaven flowed through them" (Nitobe 92).

Giving Soul to Suicide and the Sword

In his taming of the samurai, Nitobe even justifies their most savage attributes – seppuku (also known as harakiri or ritual suicide) and the sword – under the guise of Christian mores. And it all starts with the soul.

Nitobe declares that in both Western and Japanese custom, the soul is housed in the stomach. "They (The Bible's Joseph, David, Isaiah and Jeremiah) all and each endorsed the belief prevalent among the Japanese that in the abdomen was enshrined the soul" (113).

This assertion allows Nitobe to exalt suicide to a holy act, "The highest estimate placed upon honor was ample excuse with many for taking one's own life," before challenging Western readers to resist his interpretation, "I dare say that many good Christians, if only they are honest enough, will confess the fascination of, if not positive admiration for, the sublime composure with which Cato, Brutus, Petronius, and a host of other ancient worthies terminated their own earthly existence." (113-114).

The sword receives similar treatment and Nitobe declares swordsmiths to be artists, not artisans; swords not weapons, but representations of their owners' souls. He explains:

The very possession of the dangerous instrument imparts to him (the samurai) a feeling and air of self-respect and responsibility. 'He beareth not the sword in vain' (Romans 13:4). What he carries in his belt is a symbol of what he carries in his mind and heart – loyalty and honor… In times of peace .. it is worn with no more use than a crosier by a bishop or a sceptre by a king (132-133).

Nitobe's skilled manipulation dignifies and venerates even Japan's most "savage" customs. The author's dedication to and knowledge of Christianity and Western culture allowed him to forge a propaganda tool under the guise of historic fact. Nitobe hoped Bushido: The Soul of Japan would change Western opinions of Japan, raising the country's status in the world's eyes.

The Soul of Japan's Reception in The West

Bushido: The Soul of Japan became a hit with Western readers. "The slim volume," Tim Clark writes in The Bushido Code: The Eight Virtues of the Samurai, "went on to become an international bestseller," influencing some of the era's most influential men. Nitobe's treatise so impressed Teddy Roosevelt that he "bought sixty copies to share with friends" (Perez 280).

Although almost exclusively read by scholars, Nitobe's influence seeped into the Western conscious. Braudy writes, "This view of Bushido was an attractive image for Westerners… Balden-Powell has included bushido as an ideal code of honor in his exhortation to the Boy Scouts. Parliamentary groups… invoked the samurai as kindred spirit and writers on war preparedness haled up the samurai ethos of the Japanese army as a model to follow" (467).

Nitobe's account shocked readers by providing a glimpse into an unfamiliar, misunderstood world. With nothing to offer a counter point, Western readers accepted Bushido: The Soul of Japan as a factual representation of Japanese culture, and it remained the West's quintessential work on the topic for decades.

The Soul of Japan's Reception in Japan

Bushido: The Soul of Japan received a different reaction in Japan. Although bushido had yet to enter Japan's mainstream consciousness, scholars' interpretations of the concept varied and few agreed with Nitobe's representation. In fact,"Nitobe stated that he resisted the Japanese translation of his book for years out of fear of what readers might think" (Benesch 157). Many of those readers attacked Nitobe's work for its agenda and inaccuracies.

Oleg Benesch explains that most Japanese scholars did not take Nitobe's work seriously:

At the time of its initial publication, Nitobe's Bushido: The Soul Of Japan received a lukewarm reception from those Japanese who read the English edition. Tsuda Sokichi wrote a scathing critique in 1901, rejecting Nitobe's central arguments. According to Tsuda… the author knew very little about his subject. Nitobe's equation of the term bushido with the soul of Japan was flawed, as bushido could only be applied to a single class… Tsuda further chastised Nitobe for not distinguishing between historical periods. (155)

Many of Nitobe's contemporaries subscribed to an orthodox bushido based 0n Japan's ancient history. This purely Japanese form of bushido was seen as unique and superior to any foreign ideology. Orthodox writer Tetsujiro Inoue went as far as declaring European chivalry as "nothing but woman-worship" and even derided Confucianism as an inferior Chinese import (Benesch 179). The orthodox school of thought dismissed Nitobe's"corrupted," Christianized version of bushido.

To complicate matters, at the time of Bushido: The Soul of Japan's release, few Japanese even recognized the term bushido. In Musashi: The Dream of the Last Samurai Mamoru Oshii explains, "Bushido was not known among Japanese people… It appeared in literature, but was not a commonly used word."

Benesch supports Oshii's argument:

Indeed, (Bushido: The Soul of Japan) was only the second book-length specific treatment of the subject in modern Japan… Only four works in the database mention the term before 1895. The number of publications increases from a total of three in 1899 and 1900 to seven in 1901, six in 1902 and dozens per year from 1903 onward. (153)

Nitobe's treatise predated bushido as an understandable term and therefore appeared alien to its potential Japanese audience.

To make matters worse, Nitobe's book romanticized an old fashioned and exploitative class system everyone but the samurai hoped to leave behind. Accounts of samurai abusing the lower classes run rampant. Although rare, samurai could lawfully kill members of the lower class (kirisutegomen) for "surliness, discourtesy, and inappropriate conduct" (Cunnigham).

With such inequities, it's no surprise the lower classes felt no love for Japan's elite. Benesch writes, "The disdain most commoners had for the samurai has been described as legendary" (27). Not far removed from the inequities and immobility of the former class structure, the common people had no interest in idolizing or celebrating their former ruling class.

However, Nitobe wrote for Western audiences and therefore never intended for Bushido: The Soul of Japan to be read by Japanese readers. Nitobe wrote in English, referenced English sources and romanticized facts to satisfy his agenda and influence Western minds. He did not expect people with critical knowledge on the subject to read his work. "I did not intend [Bushido: The Soul of Japan] for a Japanese audience," Nitobe admitted (Benesch 165).

Critique of Inazo Nitobe

Nitobe's "fear of what (Japanese) readers might think" proved sound when Bushido: The Soul of Japan received heavy criticism in Japan. However, Nitobe soon found himself under attack as well. Many Japanese scholars accused the author of being unqualified to write on bushido, questioning his expertise on Japanese history and culture.

Unlike the era's other bushido theorists, Nitobe inhabited the outskirts of his own country and culture. He grew up studying English, sheltered from Japanese culture in Hokkaido. Nitobe would go on to live abroad, marrying an American woman and dedicating himself to Christianity. Although he eventually returned to Japan and took work as a professor, it was long after Bushido: The Soul of Japan had been written and published. Critics claimed that Nitobe's alienation from Japanese culture meant he lacked the necessary historical and cultural knowledge to write on an inherently Japanese topic like bushido.

Nitobe's astounding lack of references to Japanese history and literature add weight to this argument. Bushido: The Soul of Japan remains curiously void of factual backing, becoming a vehicle for Nitobe's equivocal ramble and yearning for an imaginary past.

The few Japanese references Nitobe made call his integrity into question. For example, although Saigo Takamori did in fact lead the Satsuma Rebellion, the heroic motivations and suicide Nitobe references were embellished to lionize Saigo as the ideal samurai.

To be fair, many of Nitobe's critics also ignored factual history and cherry picked data for their own interpretations of bushido.

Many writers on bushido, even in the 20th century, tended to propose their own theories without references to, or regard for, the ideas of other commentators on the subject. Instead, they gradually relied on carefully selected historical sources and narratives to support their theories. (Benesch 116)

However, Nitobe's contemporaries' actions don't excuse his own. At its core, Bushido: The Soul of Japan presents baseless conjecture while exposing its author's detachment from Japanese history and culture. Nitobe forgoes fact while presenting a wonky rambling on a history he does not and can not support. While proselytizing a universal morality to gain Japan favor in the West, Nitobe fails to prove bushido's actual existence.

Give Me That New Old-Time Bushido?

Popular culture presents bushido as a concrete moral code so intertwined with Japan's hallowed samurai class that the two appear inseparable. But in reality the term bushido did not exist until the twentieth century. In fact, Nitobe, one of the first scholars to embrace bushido, thought he created the term in 1900.

"Terms like budo (the martial way), bushi no michi (the way of the warrior), and yumiya no michi (the way of the bow and arrow) are far more common," Benesch writes (7). Although these terms prove that warrior ideals had a place in the Japanese consciousness, equating them to bushido would be inaccurate.

The concept bushido came into use during the Meiji era but wouldn't gain widespread acknowledgment until Meiji's end. Despite popular imagery, ancient samurai did not write about or discuss bushido. Dishonorable acts didn't end careers and lives as romanticized histories lead us to believe.

That isn't to say that ancient Japan lacked laws or moral codes – claiming such would be ridiculous. Rosalind Wiseman puts it best in her book Queen Bees and Wannabes, "We all know what an honor code is. It's a set of behavioral standards including discipline, character, fairness, and loyalty for people to uphold and live up to"(Wiseman 191). From small communities like workplaces and clubs to large institutions like religions and nations, every culture has honor codes and concepts of morality.

But popular representations of bushido, samurai, and ancient Japan depict a clear and strictly enforced code of honor. To dishonor oneself was to commit spiritual and physical suicide. Popularized after the samurai class's demise, books like Bushido: The Soul of Japan and Yamamoto Tsunetomo's Hagakure help facilitate this myth, making it seem as if samurai lived and acted according to a literal, clearly defined set of rules that never existed.

Some researchers cite kakun 家訓, or family house rules, as the origin of bushido. "In many cases the kakun were meant to serve as ethical and behavioral guidelines for the sons or heirs of the writers and often reflect concerns regarding the prosperity and the continuity of the clan" (Henry Smith).

Attributing family kakun to an overarching moral code is a leap most researchers don't take. Benesch comments, "Bushido receives little or no mention in postwar scholarship on medieval house codes… Evidence indicates that the association of bushido with (kakun) is a product of late Meiji-era interpretations" (8). Passed down from generation to generation kakun varied greatly by family. The scrolls became family heirlooms, not a set of rules to live by.

Early discourse on the subject exposes how vague warrior class values had been. "An examination of source materials and later scholarship relating to samurai morality does not reveal the existence of a single, broadly-accepted, bushi specific ethical system at any point in pre-modern Japanese history" (Benesch 14). Besides, warriors focused on victory and survival – battle didn't lend itself to counterproductive codes of honor.

Any laws or moral codes put into place during the Edo era actually served to tame Japan's wild, unprincipled warrior class as they moved from the battlefield to desk jobs. "The samurai were too busy fighting in earlier centuries, and only began to concern themselves with ethics in the relatively peaceful Edo period" (15).

With no battles to wage, the Tokugawa government relegated swords to ornaments of class, the ultimate status symbols. Samurai became upper-class bureaucrats with leisure time to spend on philosophical pursuits. Ideas of honor and etiquette frowned upon disloyalty and senseless violence, playing into the Tokugawa government's strategy to maintain control over a united Japan.

The Honorable Samurai: Fact or Fiction?

Bushido had never existed as an honor code or term in ancient Japan as Bushido: The Soul of Japan implied. Nitobe's representation of the samurai class proves itself just as contrived. Like all human beings, samurai morals varied by individual.

Honorable Warriors?

Historical accounts show that samurai did not follow an honor code, which would have been an impractical obstacle to survival, victory, and comfortable living. Timon Screech writes "We are talking mythologies. The belief that samurai ever fought to the death does not survive investigation, nor the claim that they made the sacrifice of disembowelment when atonement was required. The motto the way of the samurai is death was invented long after death had ceased to be on most samurai's minds or a reality in their lives… they were bureaucrats."

Although depicted as common practice, seppuku was not the mainstay of the samurai as Nitobe depicted. "It hurt too much," Screech explains. "Suicide actually took the form of a pretended stab carried out with a wooden sword, or even a paper fan, at which a signaled assistant would sever the head from behind, cleanly and painlessly."

Benesch writes that seppuku was "limited to hopeless situations in which a defeated warrior was certain to be subjected to torture, a common practice at the time" (16). Ignoring seppuku's factual history, writers romanticized the practice and exalted it to the ultimate form of honor.

And what of the sword, the so-called soul of the samurai? Charles Sharam explains, "Prior to [the Tokugawa era], the samurai were in fact mounted archers who were highly skilled with the bow and arrow, occasionally using other weapons if necessary. For the greater part of their history, the sword was not an important weapon to the samurai."

Depicted as the antithesis of the sword in modern media, firearms came to represent the abandonment of "samurai values." The loud foreign weapons embodied a loud, dirty (literally due to the gunpowder and smoke), dishonorable way of killing from afar. But what about archery, the samurai's original weapon of choice? Though elegant, bows fired projectiles and killed from afar – just like firearms. Shouldn't archery be viewed as just as dishonorable as guns?

Furthermore, samurai had the privilege and advantage of mounted combat. In fact, Oshii theorizes that Miyamoto Mushashi created his legendary niten-ichi 二天一, or two sworded technique for better balance and more efficient killing from the saddle. Both the shooting and cutting down of foot-soldiers from a favorable mounted position clashes with the honorable image of the grounded sword fighter popularized by modern depictions of the samurai.

In Bushido: The Soul of Japan Nitobe describes loyalty as the shining attribute of the samurai class. However, samurai sullied Japanese history with rampant examples of disloyalty. G. Cameron Hurst III writes:

In fact, one of the most troubling problems of the premodern era is the apparent discrepancy between… codes exhorting the samurai to practice loyalty and the all-too-common incidents of disloyalty which racked medieval Japanese warrior life. It would not be an exaggeration to say that most crucial battles in medieval Japan were decided by the defection – that is, the disloyalty – of one or more of the major vassals of the losing general. (517)

And although bushido denounces materialism as a corruptive force, samurai weren't the epitome of anti-materialism that bushido writers like Nitobe described. Benesch explains:

Loyalty required payment. Reciprocity was expected at every stage of the process… and most samurai would have considered their own lives to be considerably more important than the lives of their superiors… (Furthermore) repeated looting of Kyoto evidenced of a lack of ethics, and the great importance warriors placed on appearance (represented) the antithesis of the popular image of the austere and frugal samurai. (19-21)

Honorable Lifestyles?

Tokugawa ushered in an unprecedented era of peace that forever altered the live's of Japan's warrior class. Many samurai moved from the battlefield to civil service positions. As society's upper class, these samurai held cushy positions in the new era's bureaucracy. Swords became symbols of status, not battle. With ample leisure time, these samurai enjoyed hobbies such as tea ceremony and calligraphy. Others spent time in the pleasure quarters.

While peasants toiled in the fields to feed the nation and pay taxes and merchants struggled to maintain a respectable position in society, the samurai worked desk jobs for rice stipends. Disposable income afforded samurai the luxuries of materialism and the former warriors became Japan's most fashionable class. In other words, samurai represented "the one percent" (actually six to eight percent according to Don Cunningham) of the Tokugawa era.

But not all samurai enjoyed life in the upper class. Low status samurai made small stipends that barely afforded daily living. Bound by the Tokugawa era's strict laws that forbade outside unemployment, some of these samurai renounced their status to become artisans or farmers (Cunningham).

Still other Tokugawa era samurai could not find employment. These vagrants often turned to dishonorable acts. As Don Cunningham explains in Taiho-jutsu: Law and Order in the Age of the Samurai, "Facing unemployment and an ill-defined role within their new society, many samurai resorted to criminal activities, disobedience, and defiance" (Cunningham). With few prospects and mounting frustrations, these samurai dressed and spoke flamboyantly, harassed lower classes, joined gangs, and brawled in the streets.

Whether elite civil servants or unemployed ruffians, Tokugawa era samurai did little to reinforce Nitobe's depictions of an honor-bound class that set a high moral standard for other classes to aspire to.

Honorable Interpretations?

The loss of status ushered in by the Meiji government did not please those samurai accustomed to the Tokugawa system. Benesch states, "The samurai found their social status increasingly challenged by economically powerful commoners, some of whom were also purchasing or receiving samurai privileges such as the right to wear swords" (24). Rendered useless in an age of peace even the sword, "the soul" and symbol of the samurai had lost meaning. New class mobility allowed the uppity lower classes to challenge the samurai in both wealth and status.

As the Satsuma Rebellion of 1877 proves, the changes pushed some samurai to take action. "Gradually eliminating their stipends and special status… created a large group of disgruntled shizoku (samurai), a number of whom gathered around Saigo Takamori and instigated rebellion."

Romanticized histories like Bushido: The Soul of Japan and The Last Samurai, depict Saigo as a defender of truth, honor, and the purity of the warrior's code. In truth, holdouts from a bygone era rebelled, attempting to preserve their status and cushy way of life that included rice stipends, property, and nepotism. Professor Ohno points out:

The previous samurai class, now deprived of their rice salary… were particularly unhappy with the new government which was established, ironically by young samurai… Silk and tea found huge markets, soaring prices enriched farmers. Enriched farmers bought Western clothes. The merchant class grew, particularly in Yokohama… Inflation soared (and) samurai and urban populations suffered. (41-43)

Low ranking and unemployed samurai, many of whom pushed for changes, saw the Meiji era as a change for the better. A weakened class structure meant poor or unemployed samurai could seek fortune elsewhere. The abolition of the heredity system allowed for mobility. Suddenly those in high positions found incentive to work hard. Although a minority, Saigo and other top ranking samurai had the most to lose and rebelled as a result.

Lucky for Nitobe, honor is in the eye of the beholder, a concept open to interpretation. For example Nitobe cites The 47 Ronin Story as the ultimate example of loyalty, but others interpret it as a cowardly sneak attack. Japan celebrates Miyamoto Musashi as its most skilled sword-fighter, yet he arrived late to duels and "dishonorably" sneak-attacked opponents. Nitobe describes the Satsuma Rebellion as a battle of honor, not a rebellion driven by the preservation of class status.

Although Nitobe and his fellow writers lament the corruption and destruction of bushido by modernity, the concept never existed as they describe. Samurai were not the loyal, honorable, bastions of bushido that they have come to represent. Charles Sharam writes in The Samurai: Myth Versus Reality, "Samurai were a superfluous burden on Japanese civilization… that contributed little to society but drained a considerable amount of wealth. That said, their elimination in the years of the Meiji Restoration was most definitely warranted for the betterment of the nation."

Fascism – Nitobe's Unintended Consequence

Just decades after ousting the samurai, the Japanese government would find a new use for its former ruling class. Despite military victories abroad, Japanese officials felt troops lacked confidence and fighting spirit. Bushido's image of honorable samurai fighting to the death provided the solution (Oshii). The ideology that changed the West's perception of Japan would now serve to fuel fascism and the Japanese war machine.

According to Nitobe, Japan came from a long line of honorable, brave, and capable warriors that could be extended to all classes. He wrote, "In manifold ways has bushido filtered down from the social class where it originated, and acted as leaven among the masses, furnishing a moral standard for the whole people" (Nitobe).

Trickle down bushido meant even the lowliest citizen could aspire to and attain the glory and honor of a samurai. The warrior spirit was ingrained in the Japanese soul. By taking bushido mainstream, the Japanese government looked to boost its soldiers' and citizens' confidence by applying the ideology among its military and citizenry.

Furthermore, bushido justified Japan's imperialistic cause by demonstrating Japan's moral and cultural superiority to other nations. Bushido writer Suzuki Chikara "felt that both Western and Chinese thought were alien to Japan, and that the nation would have to focus on its own 'true spirit' and promote 'national spirit-ism'" (Benesch 101). Like America's Manifest Destiny and the religious zealotry that fueled the crusades, romanticized bushido served to motivate and rationalize Japan's imperialist agenda.

Now that it had found an ideology, the Japanese government had to make bushido "leaven among the masses" or moving propaganda. "Civilization and Enlightenment" and "Rich Nation, Strong Army" became wartime slogans. The nationalized education system streamlined curriculums to spread government rhetoric and foster an enlightened, battle-ready citizenry.

The national curriculum changed history to fit government agendas. "The Edo-period texts that showed the greatest nostalgia for pre-Tokugawa conditions were carefully selected, condensed, and edited to purge them of those elements which ran counter to the national project in the early twentieth century" (Benesch 21).

Mandatory texts romanticized past events and personalities. According to Oshii, "False images were created out of government necessity." Thanks to the government's agenda, unfamiliar entities like bushido, Hagakure and Miyamoto Musashi entered the mainstream conscious.

Nitobe's Bushido: The Soul of Japan gained popularity in prewar Japan thanks to its ideology and romanticism of the past. Nitobe declares, "Yamato Damashii, the soul of Japan, ultimately came to express the Volksgeist of the Island Realm" (27). Defined as the spirit of the people, Hitler embraced Volksgeist for his own fascist agenda (Griffen 255). Like bushido, Volksgeist celebrated its country's folk history, cultural heritage and race. These unrealistic nostalgias for the past sowed the seeds of fascism that would lead to the unspeakable violence and tragedies surrounding World War II.

Bushido would find its ultimate embodiment in kamikaze pilots and foot-soldiers who "honorably" sacrificed themselves for their country. "Although some Japanese were taken prisoner," David Powers of BBC writes, "most fought until they were killed or committed suicide." As these soldiers' government issued volumes of Hagakure taught, "Only a samurai prepared and willing to die at any moment can devote himself fully to his lord."

Nitobe's Legacy

Although he had never intended it, Nitobe's fanciful idealization of Japan's past had obvious fascist implications. In an eerie prediction of what was to come, Bushido: The Soul of Japan states,

Discipline in self-control can easily go too far. It can well repress the genial current of the soul. It can force pliant natures into distortions and monstrosities. It can beget bigotry, breed hypocrisy, or habituate affections. (110)

Both Nitobe and the imperialist government subverted the truth and exploited Japan's past for their own ulterior motives. Thanks to Nitobe, Japan's ancient soldiers and bureaucrats became honorable, spiritual warriors. More concerned with loyalty, benevolence, etiquette, and self-control than victory, monetary gains or rank in society, the samurai became a paradigm for readers to aspire to.

But history is ever-changing. True events fade from memory and years of interpretation's tincture, both intended and unintended, shape modern understandings of the past. Blurred mixtures of fact, opinion and fantasy enter mainstream consciousness and gain acceptance as "true" history.

Did Saigo Takamori really commit seppuku at the Satsuma Rebellion's end? Did Davy Crockett really fight to his death at the Alamo, or was he executed upon surrender as some historians believe? Was the Satsuma Rebellion a battle for virtue or for status? Was the Boston Tea Party a rebellion against unfair taxation or wealthy American merchants fighting to maintain their monopoly over tea? And what about George Washington cutting down his father's cherry tree? And his wooden teeth?

While the truth may never be known or agreed upon, it's important to question the events and the motivations behind our so-called histories. In Japan's case, government manipulated histories, including a glorified samurai class and bushido code, became propaganda that helped inspire a fanatical war machine.

Society often looks for answers to our present problems in the past. Like the current Tea Party movement's misinformed exploitation of America's past, Nitobe's bushido created a yearning for the unsubstantiated simplicity and purity of a bygone era.

As The Last Samurai proves, Nitobe's legacy lives on. Accurate or not, his simplified idealization of bushido and the samurai still garners the world's admiration. And as long as it does, popular culture will follow in the footsteps of both Inazo Nitobe and the Japanese government, exploiting their mythical image for its own motives – consumer's hard earned cash.

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。