General Secretary Xi Jinping clearly wants to prepare China for a war over Taiwan. The measures he is taking to ready its people, economy, legal system, and especially its military are clear for everyone to see. The best way to dissuade him from actually rolling the iron dice is for Washington and Taipei to work together, because neither can stop Beijing on their own. It would be a fool’s errand for Taiwan to resist a Chinese military onslaught without its chief patron and protector. And the United States needs Taiwan to hold on and hold out long enough for the U.S. military to arrive in decisive force.

Unfortunately, this is easier said than done. Many Taiwanese citizens question whether America will actually defend them. Washington’s long standing posture of strategic ambiguity is obviously one source of skepticism. But even strategic clarity toward Taipei will not solve the problem. The fact is that Washington and Taipei have a long and complicated relationship. Taiwanese voters know the United States has a long history of turning its back on them in their moment of need.

Thus, there is no question that the United States should take steps to address Taiwan’s understandable lack of faith in America’s commitment. A sensible first step is to address the backlog in arms deliveries to Taiwan, as two Kuomintang legislative staffers recently argued in these pages. And there are a range of other things Washington can do to demonstrate that it is serious about Taiwan.

But increasing Taiwanese faith in American credibility is only part of the solution. The Taiwanese people must also believe that they have what it takes to withstand a Chinese onslaught. Neither faster arms deliveries nor higher defense spending will instill this much needed self-confidence.

So, what will? Transforming the culture of the Taiwanese armed forces, especially its officer corps. As a former marine who trained Taiwanese units and a retired Taiwanese naval officer educated in the United States, we understood all too well that Taiwan’s military remains a profoundly unserious organization. It is not ready to wage war. And the Taiwanese people know it.

Therefore, any effort to enhance cross-Strait deterrence must start with the culture of its officer corps. Taiwan needs uniformed leaders who are willing to address hard truths, embrace innovation, and place strategic thinking above parochial interest, legacy systems, and bureaucratic convenience. To get from here to there, Taiwanese President Lai Ching-te ought to trim the bloated ranks of his general and flag officer corps and insist that the military finally produce a coherent blueprint for mounting a genuine, asymmetric, whole-of-society defense of Taiwan. The Lai administration should insist on — and the Kuomintang-dominated Legislative Yuan will need to support — the creation of institutional mechanisms to enhance civilian control over the military. Washington can and should help by addressing the arms backlog, if only to prevent Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense from using it as an excuse; toning down public demands for dramatically higher defense spending; making it clear that other forms of support are conditional on efforts to address these cultural problems; and helping the Lai administration develop a coherent blueprint for asymmetric defense.

A Potemkin Force

Taiwan’s military is grappling with a range of persistent problems, most of which are easy to spot by anyone (in Washington, Taipei … and Beijing) who have bothered looking. One of the most pernicious challenges is that Taiwan’s military does not have enough people. Its army — the largest of Taiwan’s armed forces and its last line of defense in a war — suffers from an endemic personnel shortage. Shortfalls are particularly acute in frontline infantry, armor, artillery, and marine combat units, which are often up to 40 percent understrength. This is not merely a recruiting issue. It reveals a fundamental misalignment in how the military organizes and prioritizes its resources. The discrepancy between combat unit manning levels and total personnel levels, which hover around 80 percent, is telling in that it underscores the degree to which Taiwan’s military prioritizes administrative staffing over operational readiness. For years, the Tsai administration (2016 to 2024) tried to address the problem by improving pay and benefits for the volunteer force. When that effort proved too expensive, President Tsai Ing-wen finally relented and (re)extended conscription from four to 12 months. The army inducted the first batch of 12-month conscripts in January 2024. Unfortunately, it will take at least five years for this scheme to get fully up and running. Even then, the plan is to send most one-year conscripts to units tasked with providing rear area security. Volunteer troops will still comprise the bulk of most frontline combat units, which means the first line of defense will remain understrength. Worse yet, the army has yet to figure out how to train all of these conscripts, as we discuss below. It is therefore entirely possible that the scheme will merely “transform” untrained conscripts into undertrained ones.

Ironically, the only thing Taiwan has enough of are generals and admirals: 308 to be exact. The ratio of general and flag officers to servicemembers is approximately 2.5 times higher than that found in the U.S. military (which is criticized by its own secretary of defense for being too top heavy.)

Even if the Ministry of National Defense magically solves its personnel shortfalls, it will still struggle to train the resulting influx of new troops. Part of the problem has to do with infrastructure. It will take time (and money) to buy and build barracks and firing ranges in a place already short on space. The bigger issue is that the armed forces do not have a culture of realistic and rigorous training. Most exercises are scripted with preordained outcomes. Although political leaders now like to tout spontaneous maneuvers, it comes across as a case of “the lady doth protest too much.” Instead, most high-profile maneuvers remain more “dog and pony show” for the media and American onlookers than a serious attempt to test and improve warfighting capabilities. Having trained this way for generations means that Taiwan does not have enough non-commissioned officers and junior officers who are themselves sufficiently well-versed in decentralized modern combat tactics, techniques, and procedures to train tens of thousands of new troops each year.

The list goes on: The services still lack a coherent, overarching doctrine and associated operational concepts to guide everything from procurement to training to warfighting (and no, the newest Quadrennial Defense Review does not fill this gap). Reserve training is still inadequate. And despite efforts by the Lai administration and civil society organizations like Forward Alliance and Spirit of America, attempts to prepare Taiwanese society for war remain incomplete. Of course, a big impediment to civil readiness is the fact that the Ministry of National Defense refuses to embrace civil defense as a core mission.

Worst of all, there is a profound gap between the Taiwanese military and the society it is sworn to defend. Many older Taiwanese — especially those aligned with Lai’s Democratic Progressive Party — view the military with suspicion because many officers identify with the opposition Kuomintang Party and because of the military’s legacy as the enforcement arm of Chiang Kai-shek’s authoritarian regime. Meanwhile, one need only strike up a conversation with younger Taiwanese to find that many consider military service a waste of time. This is in part because they know how unserious their training will be, even at 12 months, and in part because they rationally prefer to pursue a higher paying job that will allow them to move out of their parents’ home.

A Dereliction of Duty

How did the rot get so bad? Culpability rests squarely on the shoulders of Taiwan’s officer corps. It goes without saying that officers lead the military and are therefore responsible for everything that happens — or fails to happen — on their watch. But in this case, the failures represent a fundamental dereliction of duty. It was the officer corps’ responsibility to track the shifting cross-Strait military balance and to adjust its posture and preparations accordingly. This basic mandate demanded vigilance, proactivity, creativity, curiosity, and flexibility. The Taiwanese officer corps demonstrated none of these things. As a result, it is just now coming to grips with a range of profound, but slow moving, political, technological, and demographic trends.

Take, for example, the way Taiwanese generals and admirals “responded” to Taiwan’s declining birthrate. While they now routinely point to this issue as the root cause of their personnel shortages, they have been aware of this trend for more than two decades. Yet despite having ample time to adapt, the officer corps acquiesced to politically enticing decisions — such as the transition to an all-volunteer force and the shortening of conscription — without bothering to develop and offer a serious alternative plan for maintaining readiness. Even more troubling, the officer corps managed a dramatic downsizing of the force without making any meaningful attempt to also streamline its internal organizational structure. Taiwan’s military now has roughly the same number of command layers supervising 160,000 uniformed servicemembers as it did when it was half a million strong.

The same goes for Taiwanese doctrine, force structure, and force posture. Instead of responding to overwhelming evidence that Chinese military modernization had rendered their long-standing preference for small numbers of expensive, conventional, and high-profile American made ships and jets by seeking change, Taiwan’s officer corps insisted on more of the same. Even now, senior officers within the Ministry of National Defense continue to push for more fixed-wing fighters, amphibious assault ships, and costly and uncertain indigenous submarines. Meanwhile, they sideline more survivable alternatives like mobile missile systems, small and fast boats operating from civilian harbors, and territorial defense.

The Roots of Dysfunction

To cure an infection, a doctor must first find its source. Similarly, if Washington and Taipei are serious about preparing Taiwan’s military for war, they need to identify and deal with the underlying cause of its dysfunction. We believe that it all starts with organizational culture.

The scholarly literature on military change and effectiveness is clear on this point: culture matters. A healthy military culture — one capable of adapting in peacetime and in wartime — cultivates flexibility, curiosity, and honest internal debate. Subordinates must feel empowered to challenge assumptions. Senior leaders must value — or at least not punish — dissent and feedback while also remaining sensitive to top-down, political input.

Taiwan’s military culture exhibits virtually none of these attributes. It is rigid, hierarchical, risk-averse, and allergic to outside influence. Perhaps the most telling symptom of this dysfunction is the growing number of retired generals who now appear on television to diagnose systemic flaws — problems they made no effort to fix when they held the power to do so. This pattern reflects a deeper cultural malaise: one of deflection, inertia, and institutional self-preservation.

Like all cultures, this one is the product of a complex interplay of factors. Three are worth examining in detail: an identity built around a military academy and ethos modeled after the Soviet military; enduring isolation from the rest of Taiwanese society; and, after 1979, a lack of exposure to partner militaries.

Whampoa-Centric Institutional Identity

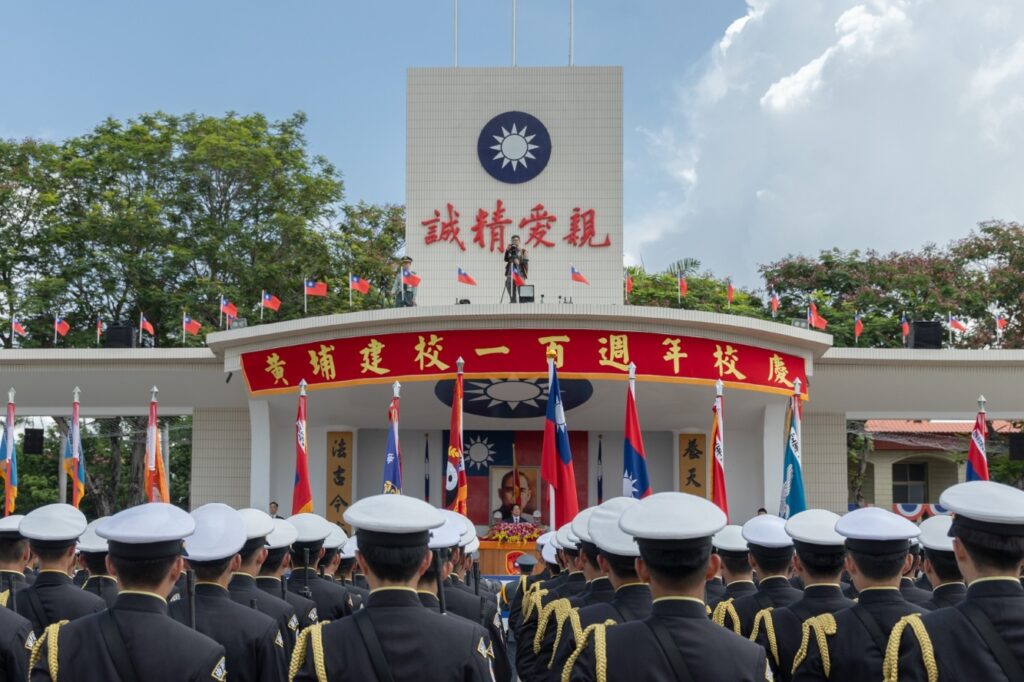

To understand how the Taiwanese officer corps understands and defines itself, one must start with the Whampoa Military Academy. Established in China in 1924, the Nationalists modeled the Whampoa Military Academy after the Soviet Red Army (Moscow even sent one of its own, Pavel Pavlov, to serve as the academy’s first chief advisor).

Nearly a century later, Whampoa’s cultural genetic material persists throughout Taiwan’s military institutions such that Taiwanese military culture also remains deeply Whampoa-centric. To reinforce this shared identity, every cadet from every service academy must attend boot camp at Whampoa (renamed the Republic of China Military Academy after it relocated to Kaohsiung). Every year, the service academies also participate in the Pu Guang Yan Xi (“Glory of Whampoa Exercise”) to commemorate the academy’s anniversary. Last year, Lai even joined in on the festivities. This symbolic centralization reinforces the dominance of army-centric values and thinking, often to the detriment of joint force development and innovation. This “cult of the Whampoa” has come at a high price for Taiwan’s military by reinforcing norms and values that privilege patronage over competence, political connections over merit, and loyalty above all else.

Domestic Isolation and Cultural Entrenchment

Internally, the military’s aforementioned cultural isolation from Taiwanese society has deepened its resistance to reform. For generations, military service has carried a negative social stigma, encapsulated by the old saying: “Good men don’t become soldiers; good iron doesn’t become nails.” Nearly four decades of martial law only served to reinforce this alienation given that Chiang and his son used the military as a tool of political repression and authoritarian control.

Under the Kuomintang’s one-party rule, Chiang indoctrinated the military in the idea of the “trinity of enemies”: Chinese Communists, Taiwanese independence supporters, and domestic conspirators. Of course, these latter two groups eventually evolved into the Democratic Progressive Party, which rose to political power through the democratic process. However legitimate the Democratic Progressive Party may have been in the eyes of Taiwanese voters, its position atop the government created a deep sense of cognitive dissonance within the officer corps, because their historical “enemies” were now in charge.

Beyond orienting Taiwan’s senior uniformed generals and admirals against their Democratic Progressive Party leaders, cultural isolation had another insidious effect: it allowed the officer corps to preserve outdated traditions from the Chiang era. Officers who think differently or challenge the “status quo” are often marginalized, if not forced out altogether. This sense of being disrespected and misunderstood by broader society has only entrenched the officer corps further into a defensive, inward-looking posture that resists external scrutiny and reform.

International Isolation and Stagnation

Nor can we ignore the role that international isolation played in terms of shielding the officer corps from the pressure to embrace cultural change. Before the United States severed formal diplomatic ties with the Republic of China, U.S. military personnel in the Taiwan Defense Command provided valuable interaction and training opportunities. Unfortunately, those exchanges had minimal cultural impact given that they occurred under the shadow of authoritarian rule and largely failed to challenge entrenched norms.

After 1979, international military exchanges virtually ceased overnight. Aside from occasional (and purely transactional) arms sales, Taiwanese officers were cut off from their foreign peers. It was not until the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis in the late 1990s that the United States began to reassess the readiness of both its own forces and those of Taiwan. Key U.S. officials such as Kurt Campbell and Randy Schriver launched renewed efforts to reengage Taiwan through military training and advisory programs in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Nevertheless, the two decades of isolation prior to that had already solidified a conservative, insular leadership culture.

Today’s senior military leaders came of age during those lost decades. In a Confucian society where seniority is often equated with wisdom (the higher the rank, the greater the presumed knowledge), challenging authority is not only discouraged but often viewed as insubordination. The notion that a junior officer — or worse, an outsider — might have a better idea is inconceivable to many within the upper ranks. This cultural rigidity continues to obstruct the adoption of innovative tactics, asymmetric strategies, and reforms necessary for modern warfare.

To Change an Army

This culture has proven remarkably resilient and resistant to change. It remains steeped in tradition, constrained by hierarchy, and guarded against outside influence and persists even in the face of renewed U.S.-Taiwanese military-to-military security cooperation. The harsh reality is that even in 2025, Taiwan’s military still has more in common with a Soviet model than it does modern, Western armed forces.

Cultural change is hard. Thankfully, it can and does happen. But Taipei and Washington should not wait around for Taiwan’s military to change itself. Here are three ways the Lai and Trump administrations can begin to address some of these challenges.

First, Lai needs to articulate a clear vision for how he expects his officer corps to operate. Before doing so, he and his top advisors will need to immerse themselves in the details of modern warfare and the nuances of the Taiwanese military bureaucracy — topics Taiwanese politicians in both parties have long been far too happy to elide. Although scholars of military reform disagree about a lot of things, there is a clear consensus that adaptive military organizations should possess a culture that nurtures innovation, initiative, and introspection. Senior officers need to actively encourage questioning, tolerate dissent, empower subordinates, and embrace lessons from history and realistic training exercises. And they must demonstrate the humility to imagine new approaches and to invite and reward input from below.

Second, Lai should cull the herd of Taiwanese general and flag officers. The biggest source of resistance to change has long emanated from the senior-most ranks. In any case, there are simply too many generals and admirals. With nearly one for every 500 troops, this top-heavy apparatus naturally exacerbates a bloated and overly centralized command structure and deeply ingrained bureaucratic inertia. Lai should of course cut his general and flag officer corps with a scalpel, not a broadsword, because there are those who support reform.

Instead, Lai will need to act with precision, sending generals and admirals who are clearly “retired on active duty” as well as those who actively subvert asymmetric defense transformation (he knows who they are), out to pasture. Instead of replacing them with the next highest-ranking officer in line, Lai should be willing to identify and promote pro-reform leaders to the top echelons of command, regardless of their current rank.

To oversee implementation, Lai and the Legislative Yuan will need to work together to create institutional mechanisms to help future presidents more effectively monitor and steer the military. Even though President Lai took the important step of putting a career civilian in charge of the military, Minister Wellington Koo still lacks an institutional equivalent to the Office of the Secretary of Defense through which he can effectively monitor the Ministry of National Defense. Civilian oversight suffers as a result.

Third, while the United States has a terrible track record of facilitating cultural change in partner militaries, there are still ways it can assist from the sidelines. For example, Washington should make it clear that cultural change of the sort we call for in this article needs to precede other reform efforts lest they fail to take root. The United States should, of course, take reasonable steps to reduce the existing arms sales backlog, if only to preempt the Ministry of National Defense’s “go to” excuse that late deliveries are preventing it from doing its job.

Beyond that, Washington should put new arms sales on the backburner while downplaying calls for Taiwan to dramatically increase its defense spending. We recognize that pushing Taipei to spend more on defense plays well in Washington and that spending is important. But it bears repeating: All the arms and all the money in the world cannot solve a fundamentally cultural problem. Even military-to-military training is unlikely to work absent a deeper, cultural reform. Generations of tactical and operational reform attempts by foreign advisors — ranging from Joseph Stilwell to U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group officers and today’s U.S. Army and Marine Corps trainers — have repeatedly failed to take root, largely because the culture itself has not been conducive to change.

Worse yet, without a change in culture, more arms and more spending might actually backfire. Many Taiwanese already consider U.S. arms sales as a corrupt form of protection money. As a result, the more weapons the United States sells to Taiwan, the less incentive the Taiwanese people have to provide for their own defense, because they assume the United States will now be “on the hook” to defend them. It should go without saying that pouring more money into an inefficient and dysfunctional system is a blueprint for waste that will only serve to further alienate Taiwanese taxpayers from their guardians.

Washington can also help pro-change civilians and officers prepare a clear roadmap for reform. Defense transformation is a complex undertaking that necessarily involves countless government agencies, private companies, and nongovernmental organizations. An overarching blueprint, with agreed-upon milestones, will help both sides orchestrate their efforts. It will allow Washington to measure progress and tailor its support, while giving Taiwanese civilian officials a tool for maintaining oversight. The single most important milestone in this plan — one on which the next administration should insist — is the dissemination of a military doctrine for defending Taiwan asymmetrically. Taiwan’s armed forces have not had such an overarching asymmetric plan to coordinate operations, training, and acquisitions since rejecting Adm. Lee Hsi-min’s Overall Defense Concept.

The situation is dire, not hopeless. Absent a fundamental shift in military culture, even the best strategies, budgets, and technologies may fail to translate into real readiness. As Taiwan faces an increasingly assertive and capable adversary across the Strait, time is running short to close this cultural gap.

Yuster Yu is the senior executive advisor of Octon International and a senior advisor of the iScann Group. A retired Taiwanese naval officer, he served on Taiwan’s National Security Council and as a naval attaché to the United States. He is a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute, the U.S. Pacific Fleet Anti-Submarine Warfare Officer Course, and Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Michael A. Hunzeker (@MichaelHunzeker) is an associate professor at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government, where he also directs the Taiwan Security Monitor. He served in the Marine Corps from 2000 to 2006.

Image: Taiwan Presidential Office via Wikimedia Commons

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。