向巴比桑學習

1945 年 8 月 14 日,日本政府正式同意向二戰同盟國投降。不到兩週後,第一批美國軍隊開始在本州島主島的機場和港口登陸,開始盟軍佔領日本(1945-1952)。到 1945 年底,近 50 萬美國士兵駐紮在全國各地。 1946 年,英聯邦軍隊的另外 4 萬多名士兵(英國人、澳洲人、印度人和紐西蘭人)加入了他們的行列。

1946 年和 1947 年期間,駐日盟軍士兵數量急劇下降,因為很明顯,佔領軍基本上不會遭到反對,而且是和平的。儘管如此,在成立的七年裡,散佈在日本四個主要島嶼上的數十個基地駐紮著不少於 10 萬名軍事人員(其中大多數是 18 歲至 24 歲的男性)。 在韓戰期間(1951-1953),美國在日本的駐軍人數實際上再次增加,到1952年達到26萬名美國士兵 。結束佔領的談判包括日本和美國之間的雙邊安全條約,該條約規定美國軍事基地無限期繼續存在。如今,美國在日本仍有約85處軍事設施。大多數位於沖繩島,沖繩島是美軍控制的島嶼群,直到 1972 年回歸日本為止,但主要島嶼上仍然存在一些屬於美國海軍陸戰隊的重要基地(岩國、富士營)、空軍基地陸軍(橫田、三澤)、海軍(佐世保、橫須賀、厚木)、陸軍(座間)。[2]

數十萬(主要是美國士兵)不斷地騎自行車進出日本,對兩國和世界產生了巨大影響,至今仍在產生影響。雖然學者們研究了佔領的許多方面,但直到最近,這種趨勢主要集中在盟軍(主要是美國)的政策和利益如何影響日本,特別是日本精英:政治家、政策制定者的單向和自上而下的故事上。較新的研究探討了日本人自身在塑造職業中的積極作用,以及普通和精英日本人職業經歷中的一些更常見的方面。特別是後一個計畫的結果是,人們重新認識到盟軍士兵及其基地對日本日常生活的影響。 然而,仍然容易被忽視的是日本對其佔領者同樣深遠的影響。在日本完成服役的年輕的美國、澳洲和其他盟軍士兵也受到了他們的經歷的影響,他們在離開日本或進入軍事生涯的其他站點時將這些經歷帶回家。

特別是在美國流行文化中可以找到與美國大兵的經驗直接相關的易於取得的資料。本文探討了一個例子:由一名海軍軍人在佔領時期最後兩年繪製和撰寫的漫畫集,並於 1953 年在日本和美國以書名《Babysan:私人審視日本佔領》一書的形式重新出版。[3] 在以下各節中,我將提供一些建議,說明如何解讀《巴比桑》,作為深入了解日本、美國及其他地區的佔領者和被佔領者的佔領的一種手段。

I. Babysan 告訴我們什麼

《Babysan》 的主要作者比爾·休謨(Bill Hume,1916-2009 年)是來自密蘇裡州的海軍預備役軍人,1951 年應徵入伍,在日本厚木海軍空軍基地服役。休謨是平民生活中的商業藝術家,他開始在各種軍事期刊上發表有關美國士兵的漫畫,例如太平洋版的《星條旗》和《海軍時報》。 他最著名的漫畫涉及海軍軍人與年輕的日本女性(他稱她們為“Babysan”)的色情互動。休謨和他的合著者、海軍記者約翰·安納裡諾(John Annarino,1930-2009 年)在《Babysan》中解釋說,這個名字是美國和日本的混合體:

San可以被認為是先生、夫人、主人或小姐的意思。那麼,Babysan 可以直譯為「寶貝小姐」。美國人在街上看到一個陌生的女孩,不能只是大喊:“嘿,寶貝!”他在日本,禮貌是必需品而不是奢侈品,因此他巧妙地加上了「尊重」這個稱呼。它加快了介紹速度。 [巴比桑,16]

最直接的是,巴比桑讓我們深入了解美國士兵實際上如何對待日本平民的關鍵問題:佔領者與被佔領者之間關係的本質是什麼?例如,除了解釋「Babysan」一詞的起源之外,上面的引文還生動地描繪了佔領時代街道上常見的場景。盟軍士兵也不僅僅只是向日本婦女大聲問候。近年來,許多研究探討了日本被佔領期間,就像二戰後其他國家被佔領期間一樣,佔領軍和平民之間普遍存在性關係——或者軍方不贊成地稱之為“兄弟化”。 。 在佔領初期,日本政府為娛樂(和安撫)盟軍士兵而設立的妓院和其他設施中,有多達 70,000 名婦女在那裡賣淫。數以萬計的其他日本人在軍事設施內及其周圍以更隨意、私密的方式用性恩惠換取金錢或物品。然而《巴比桑》中描繪的女性並不完全是一個普通的性工作者——或者人們常說的「盼盼」 ——她們靠與軍人的短期性接觸為生。相反,休謨關注的是有時被稱為“ onrii”(來自“唯一”或“只有一個”)的灰色類別,即一次與“只有一個”穿制服的情人建立連續的、表面上一夫一妻制關係的女性,並獲得各種形式的物質補償作為回報。[4]

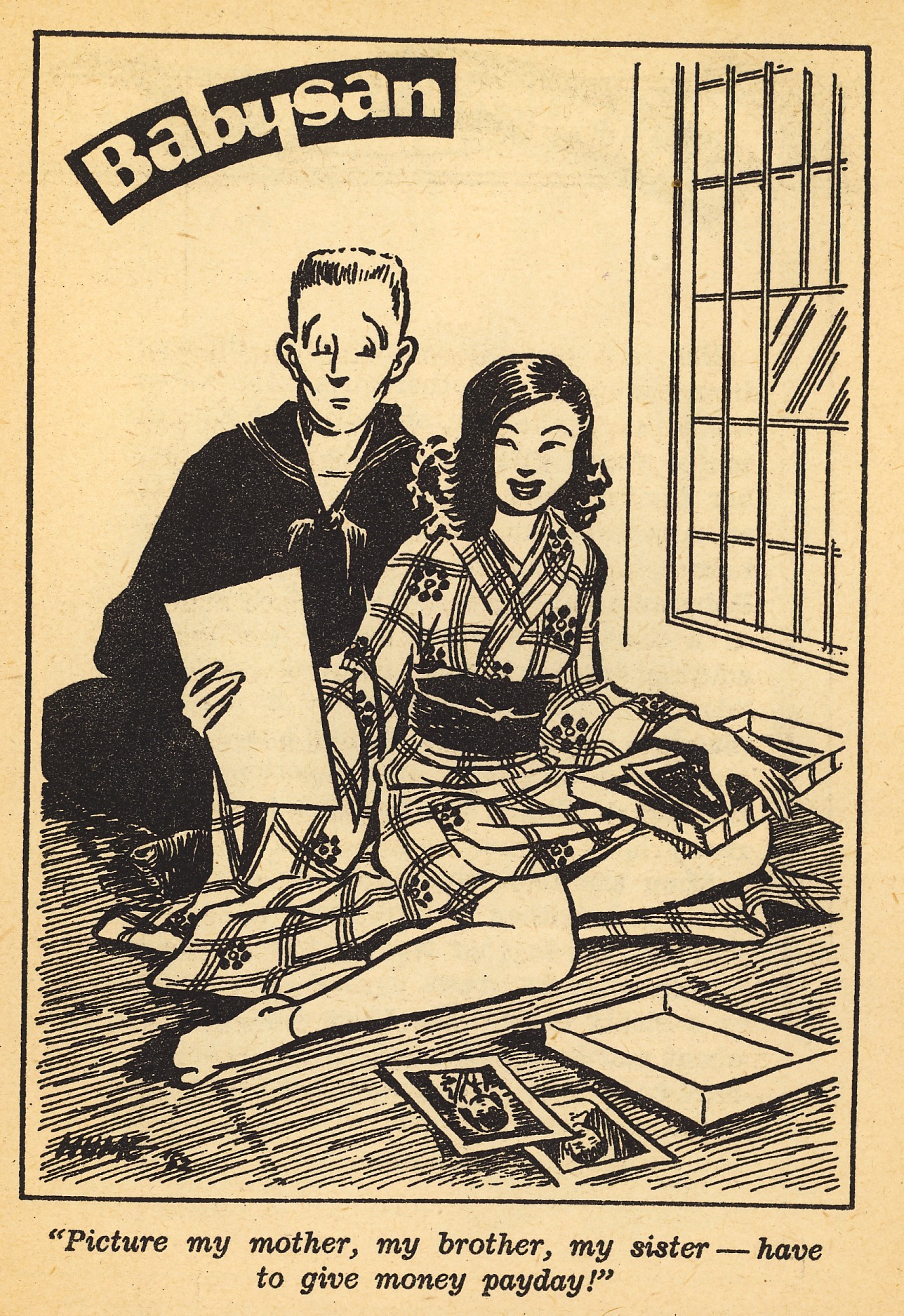

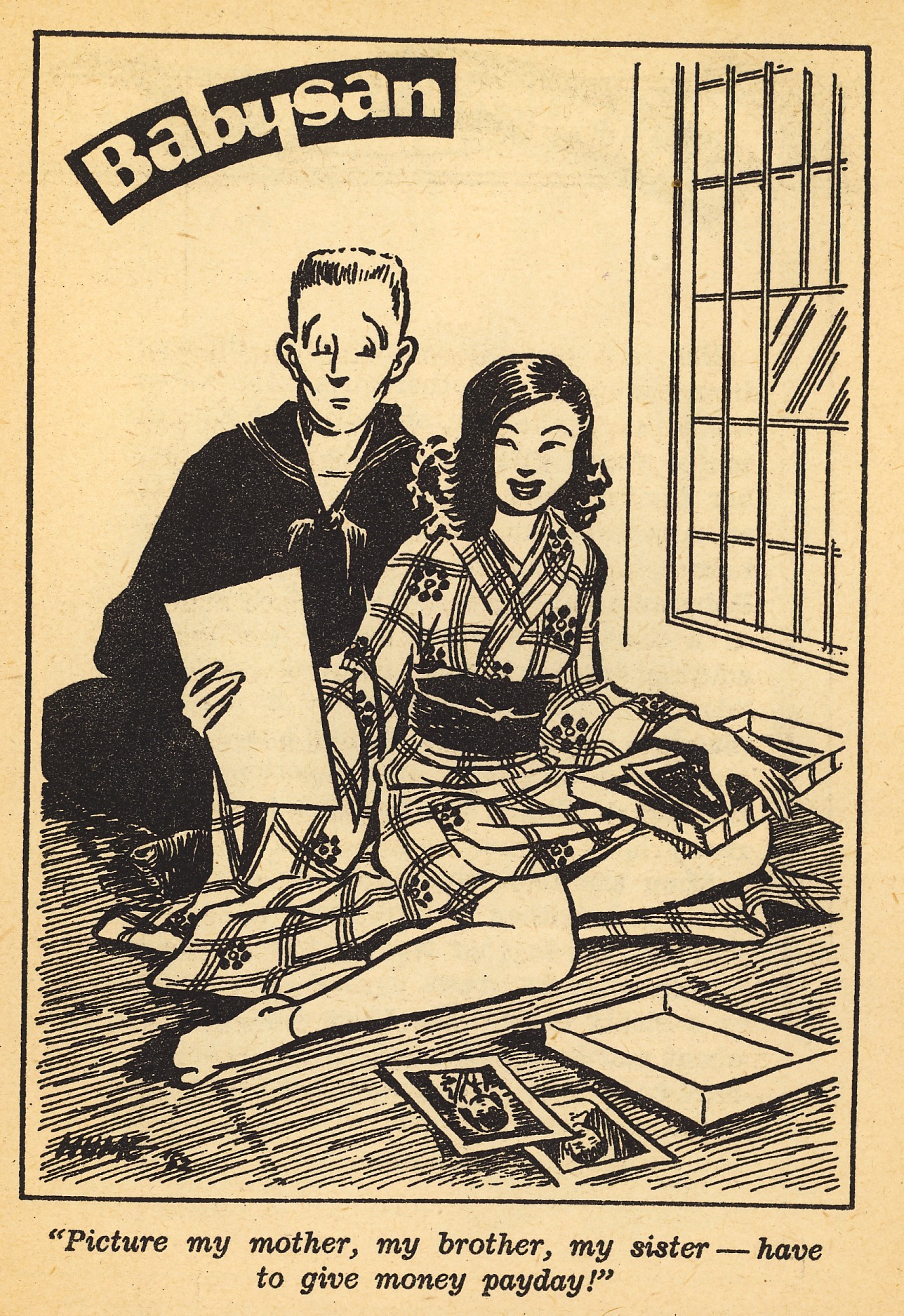

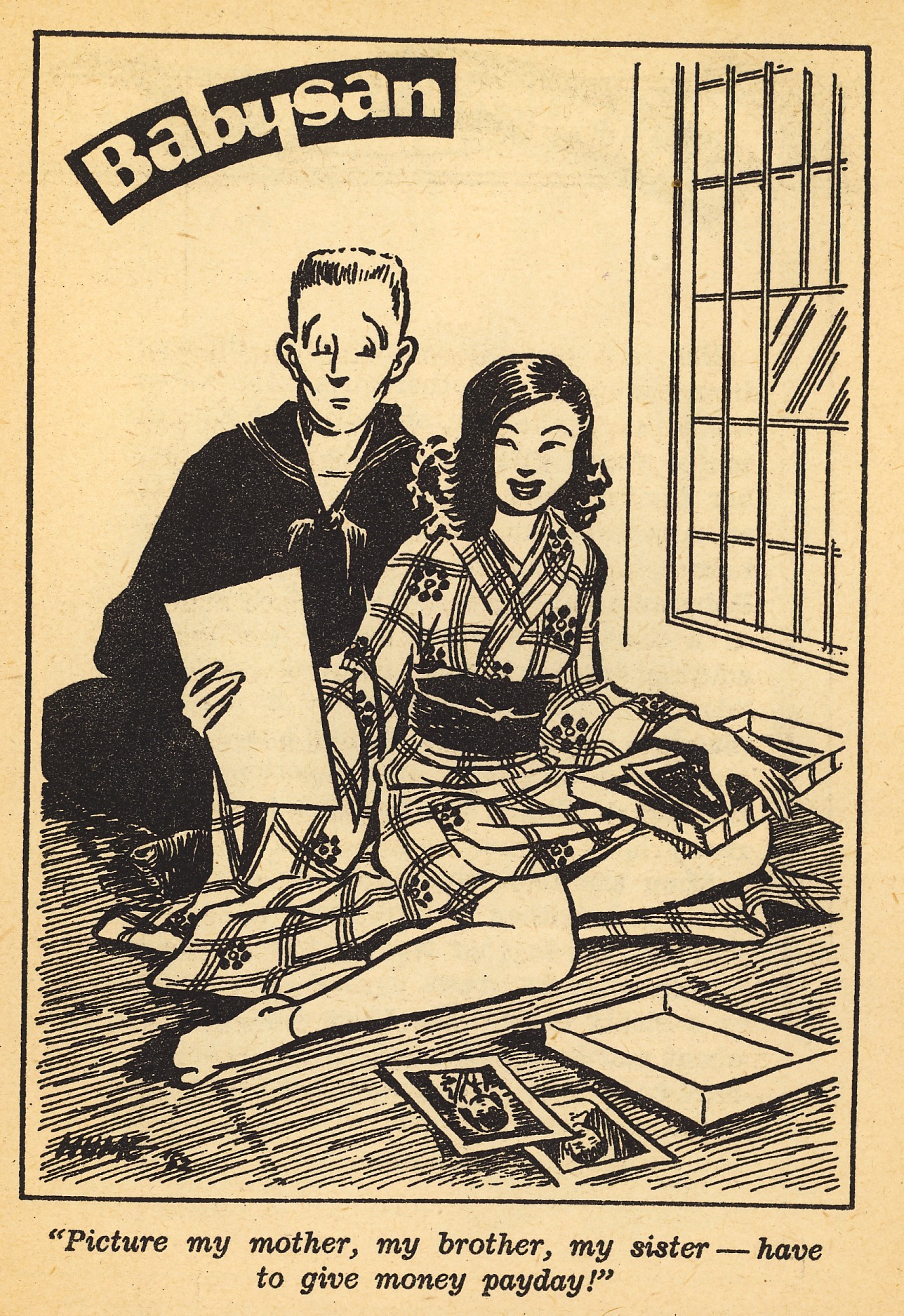

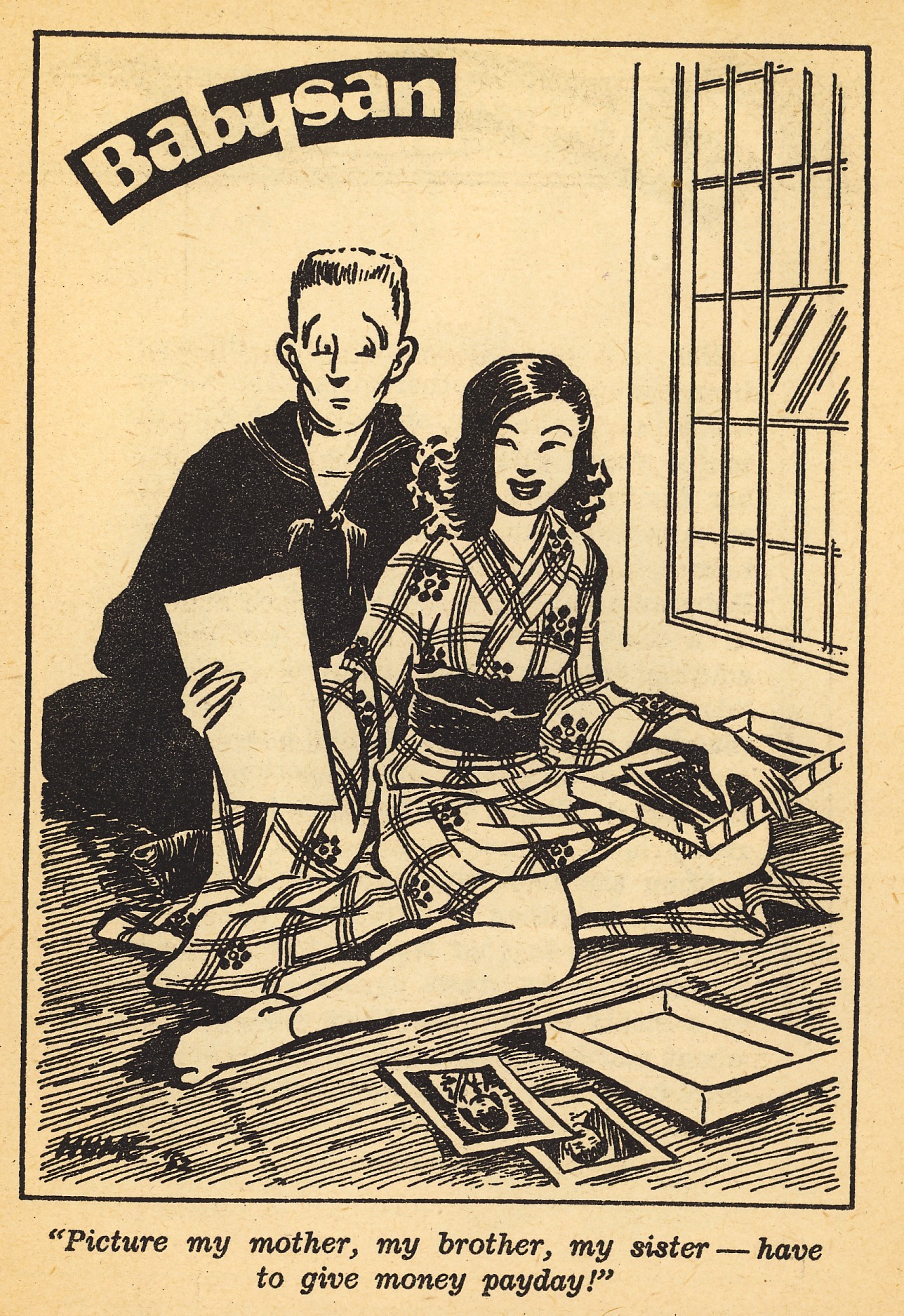

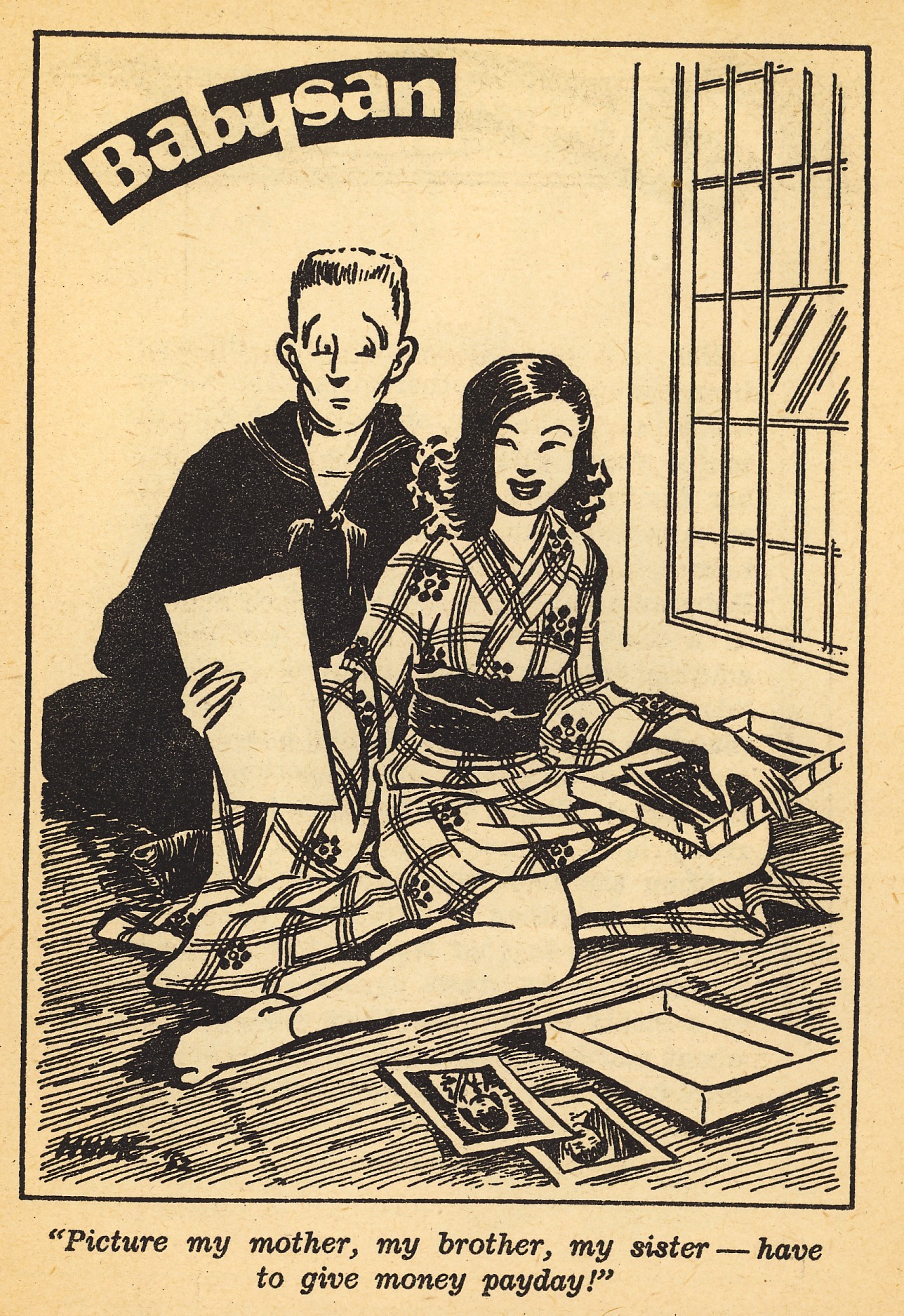

作為一部由美國軍人製作並為美國軍人製作的文件,《巴比桑》可能比它所描述的女性更多地揭示了他們的情況——但這裡對後者及其世界有真實的、有時是間接的洞察。例如,《巴巴桑》中的大部分幽默都源於美國水手對新女友的善意但常常天真的期望(忠誠、浪漫的依戀、經常發生性行為)與日本女人務實甚至欺騙性的決心之間的緊張關係。幾部漫畫指出,她聲稱自己有一個家庭需要養活,而她愛人的禮物對於他們以及她自己的生存都是必要的。 [圖1]

圖1

她的過去可能與許多其他女孩沒有太大不同。她的父親在戰爭中喪生,儘管她只是一個小女孩,但她必須工作來養家糊口。 。 。 。 年邁的母親正彎著腰在稻田裡工作。她的哥哥長大後想成為棒球運動員,但他當然是個體弱多病的孩子。巴比桑講述的關於她家人的故事有時令人難以置信。他們的體溫隨著巴比桑的經濟狀況而升降,這似乎有些不可思議。 [巴比桑,96]

作者對此表示懷疑,但日本的許多年輕女性,就像世界各地遭受戰爭蹂躪的國家一樣,確實發現自己陷入了這樣的困境,而一些人能夠獲得盟軍人員帶來的貨物和現金,這有助於支持在物質極度匱乏的時期,擴大家庭和他人的網絡。

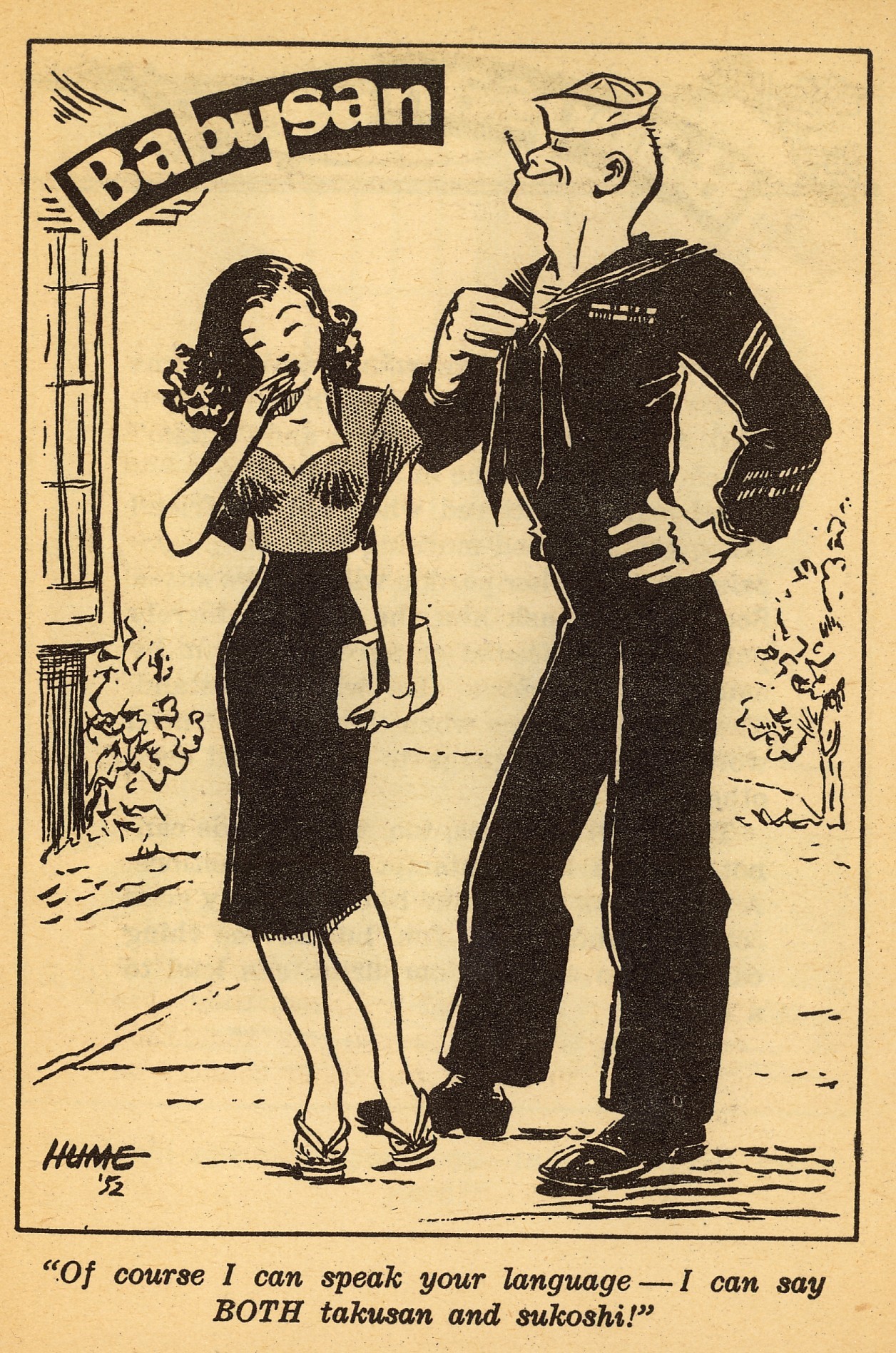

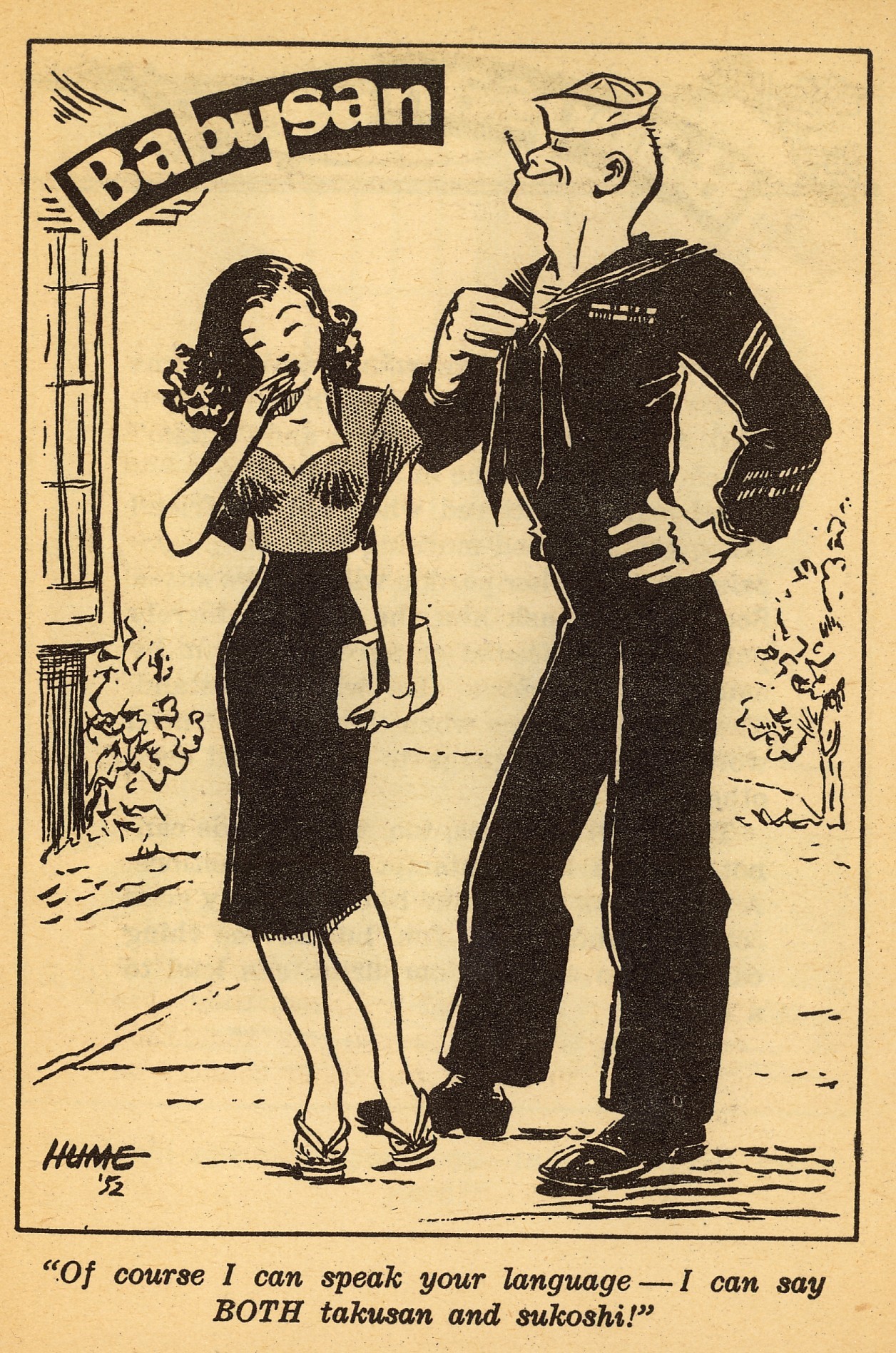

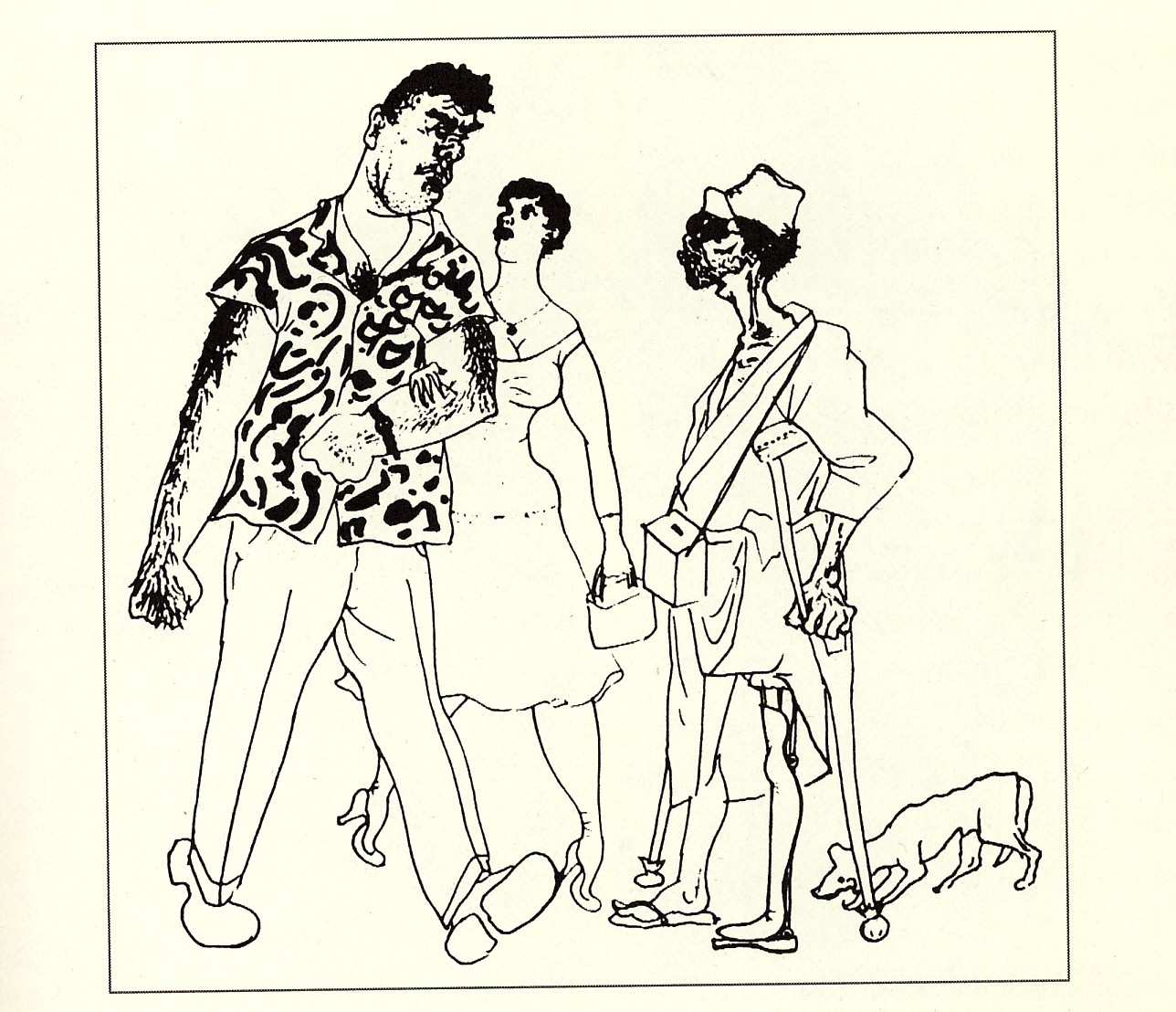

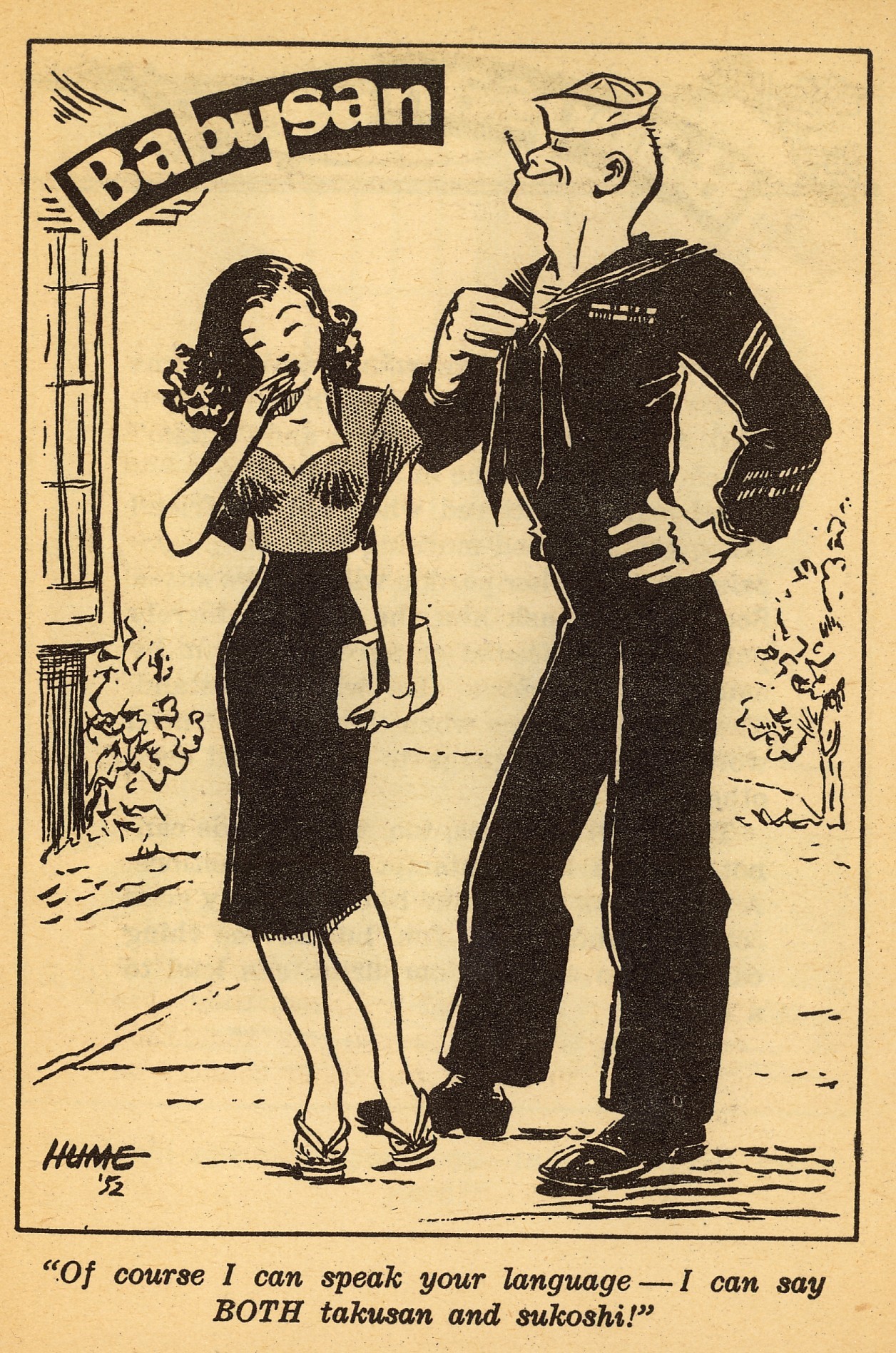

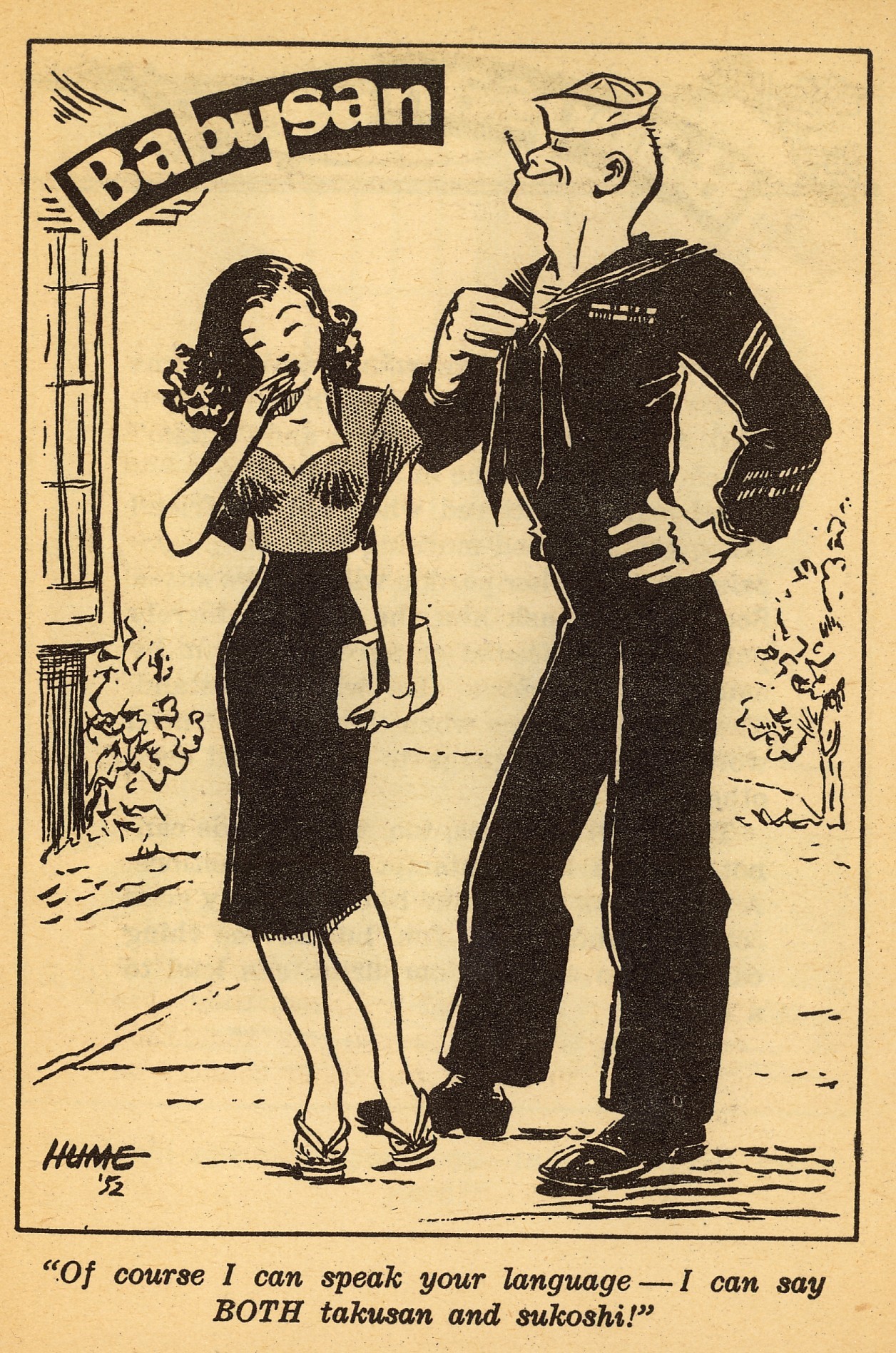

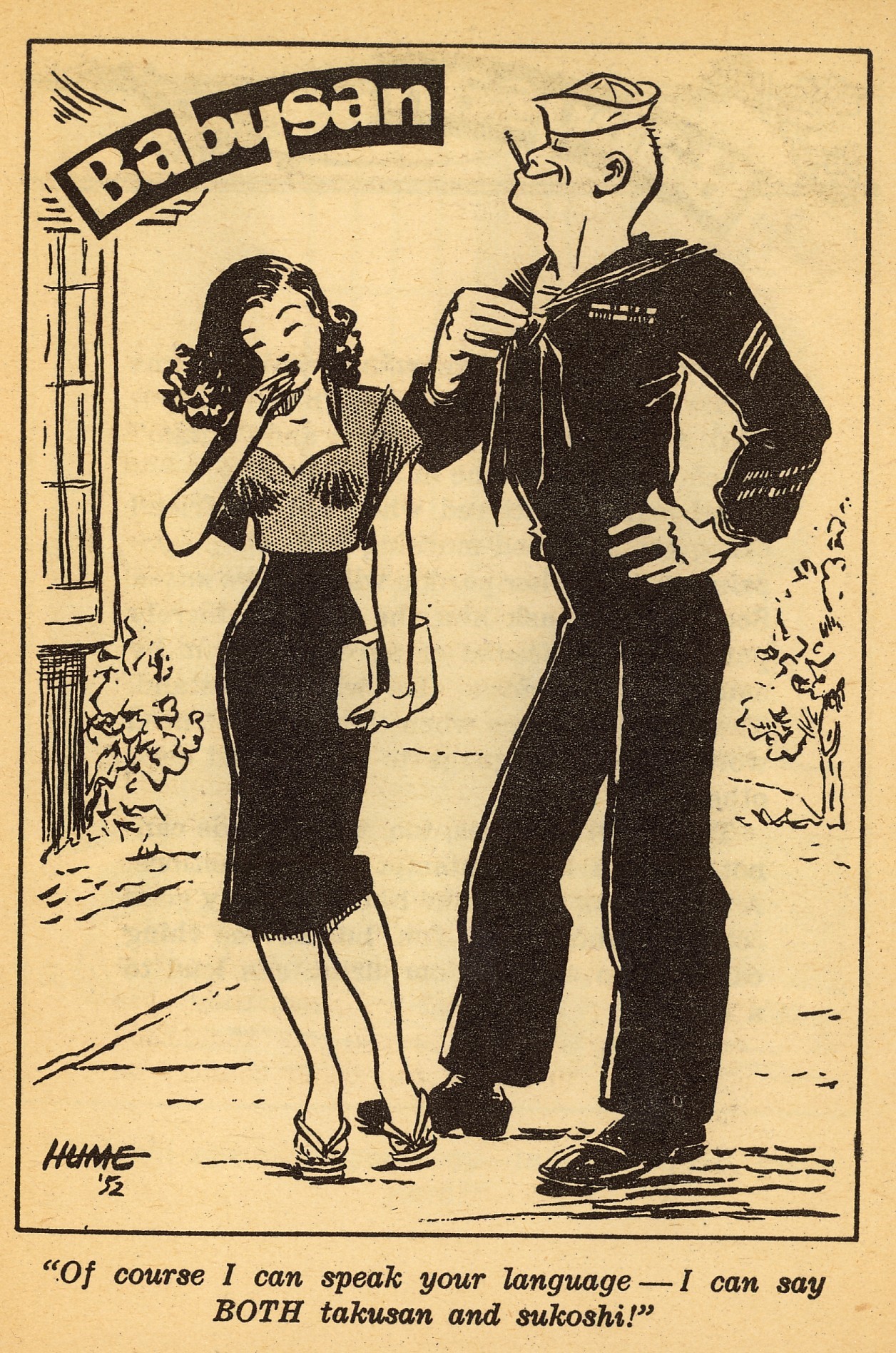

同樣可信的還有巴比桑所揭示的美國和日本文化的混合體,這種混合體幾乎立即出現在軍人和土著婦女之間的接觸空間中。 「巴比桑」一詞,以及漫畫中出現的許多其他「Panglish」例子(以及「巴比桑」末尾的一個模擬有用的術語表中),證明了軍事佔領所釋放的語言創造力。正如幾幅漫畫以及書中的術語表所表明的那樣,日本女性用英語交流的能力是透過軍人熟悉某些日語術語和短語的方式來提高的[ Babysan , 89, 124-127]。由此產生的洋涇浜語並不是一種平等的混合體——權力不平衡不可避免地有利於英語——但這一現象暗示了佔領的影響可能包括某種程度的日本化,而不僅僅是單向的美國化或西方化。 [圖2]

圖2

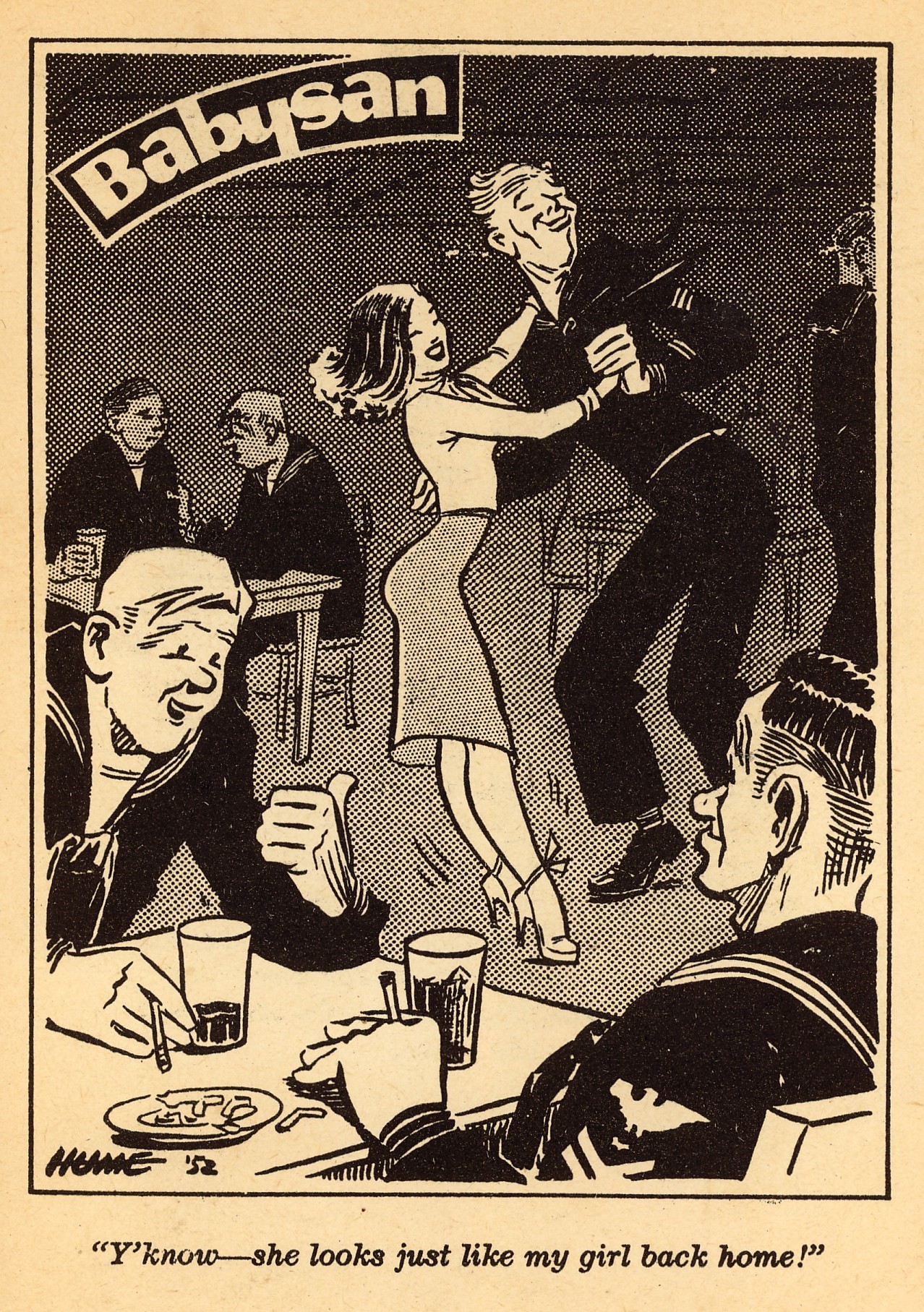

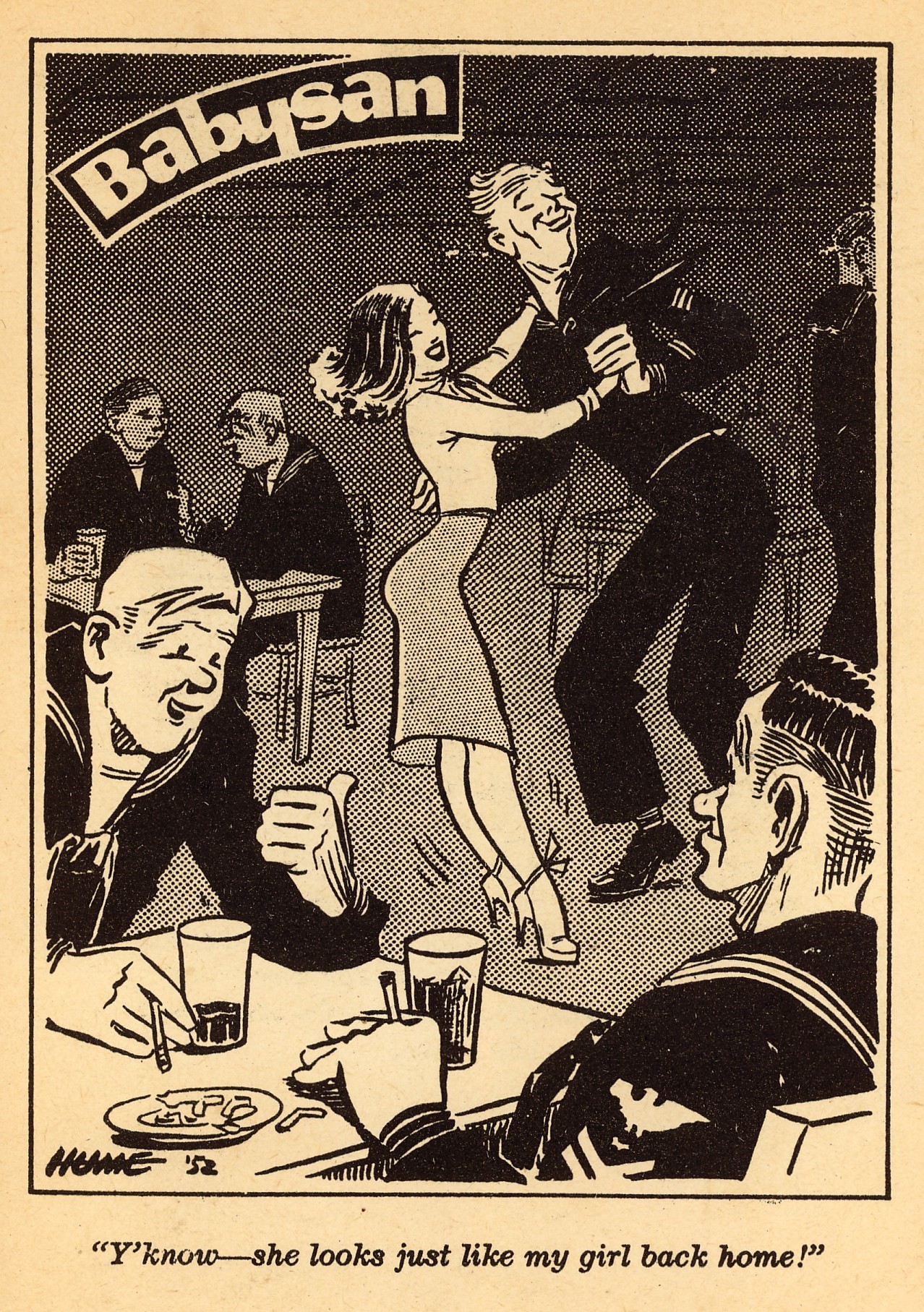

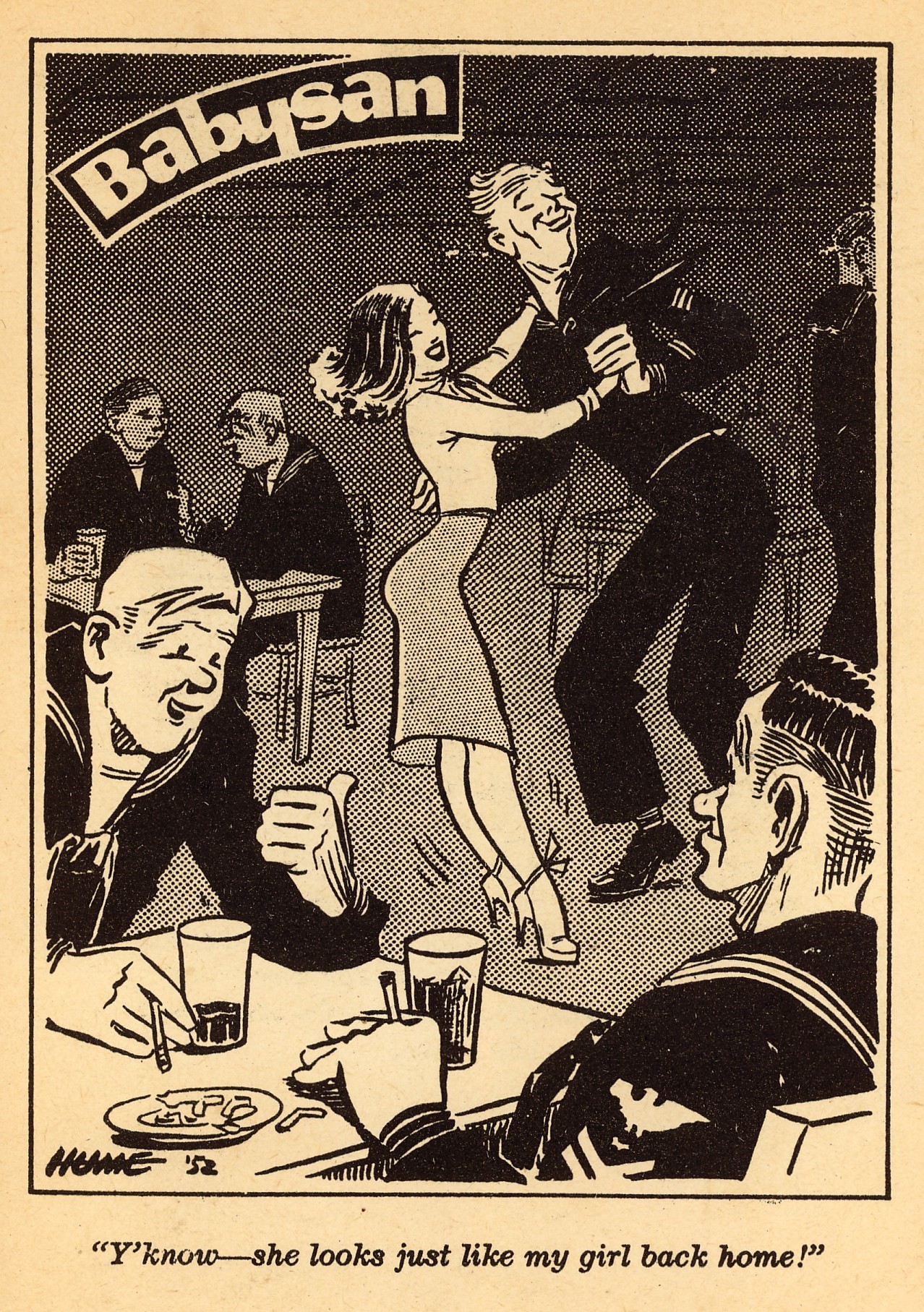

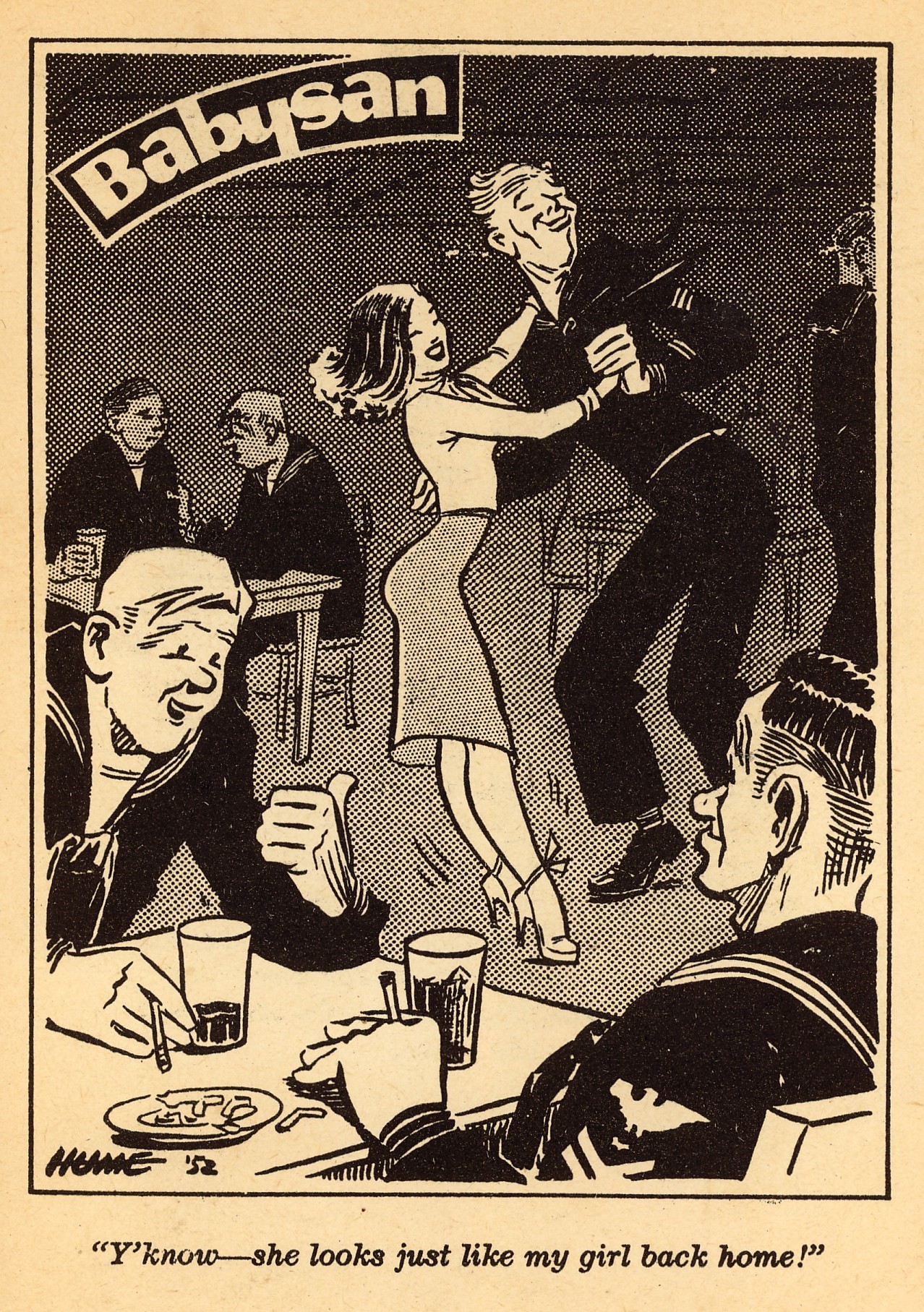

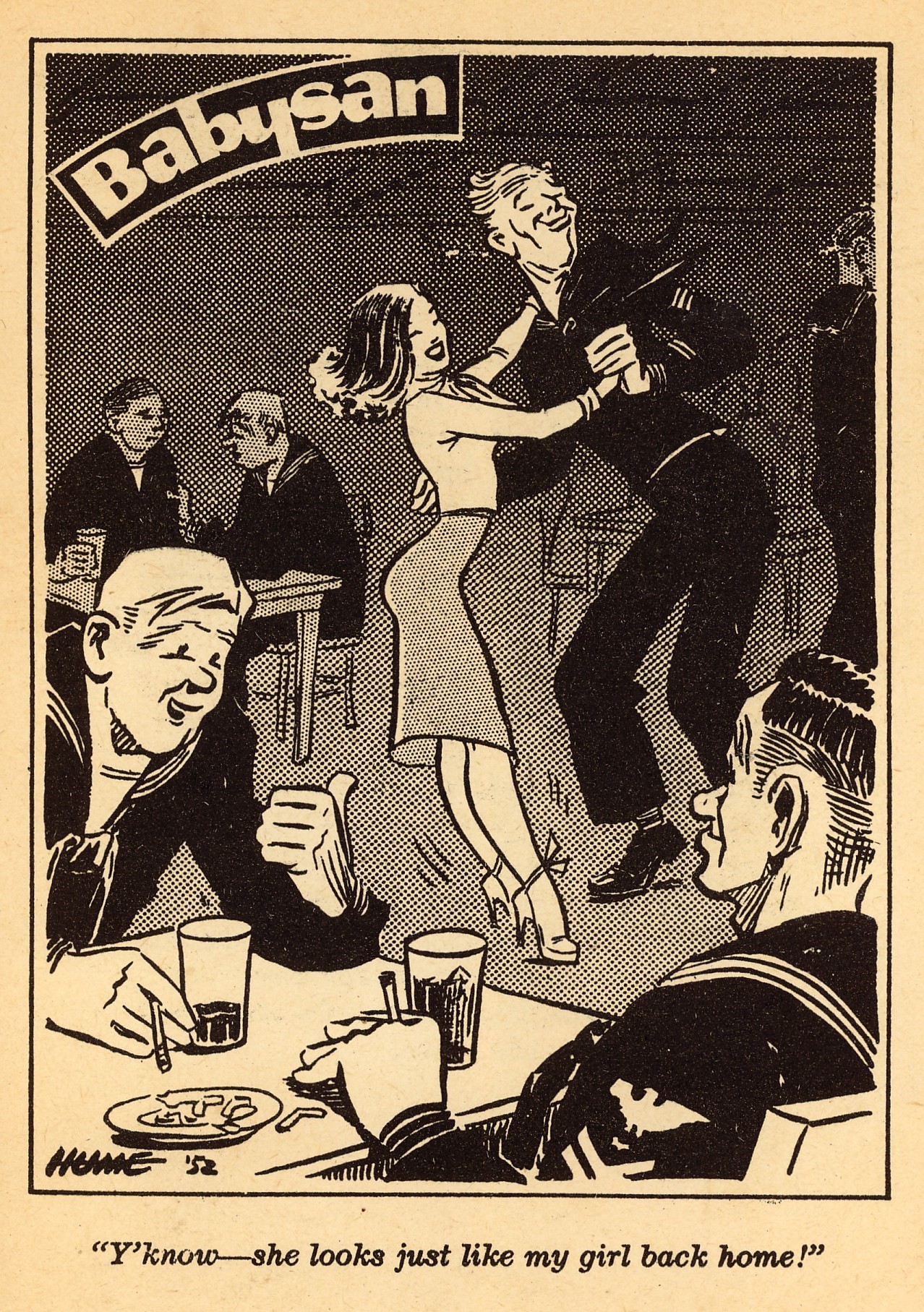

同樣,也有一些文獻提到了另一種在佔領者和被佔領者接觸區蓬勃發展的混合文化形式:流行音樂。一幅漫畫描繪了巴比桑與一名水手「在俱樂部地板上跳來跳去」的情景。 [圖3]

圖3

隨附的文字將曲調標識為“日本倫巴”[ Babysan,10-11]。日本唱片公司 Nippon Columbia 於 1951 年發行的“日本倫巴”只是眾多熱門歌曲之一,例如“Tokyo Boogie Woogie”(1949 年)或“Gomen-nasai(請原諒我)”(1953 年)。或最近被佔領)的日本,並在日本及其以外的世界其他地區流通。[5]

二. Babysan 沒有告訴我們什麼

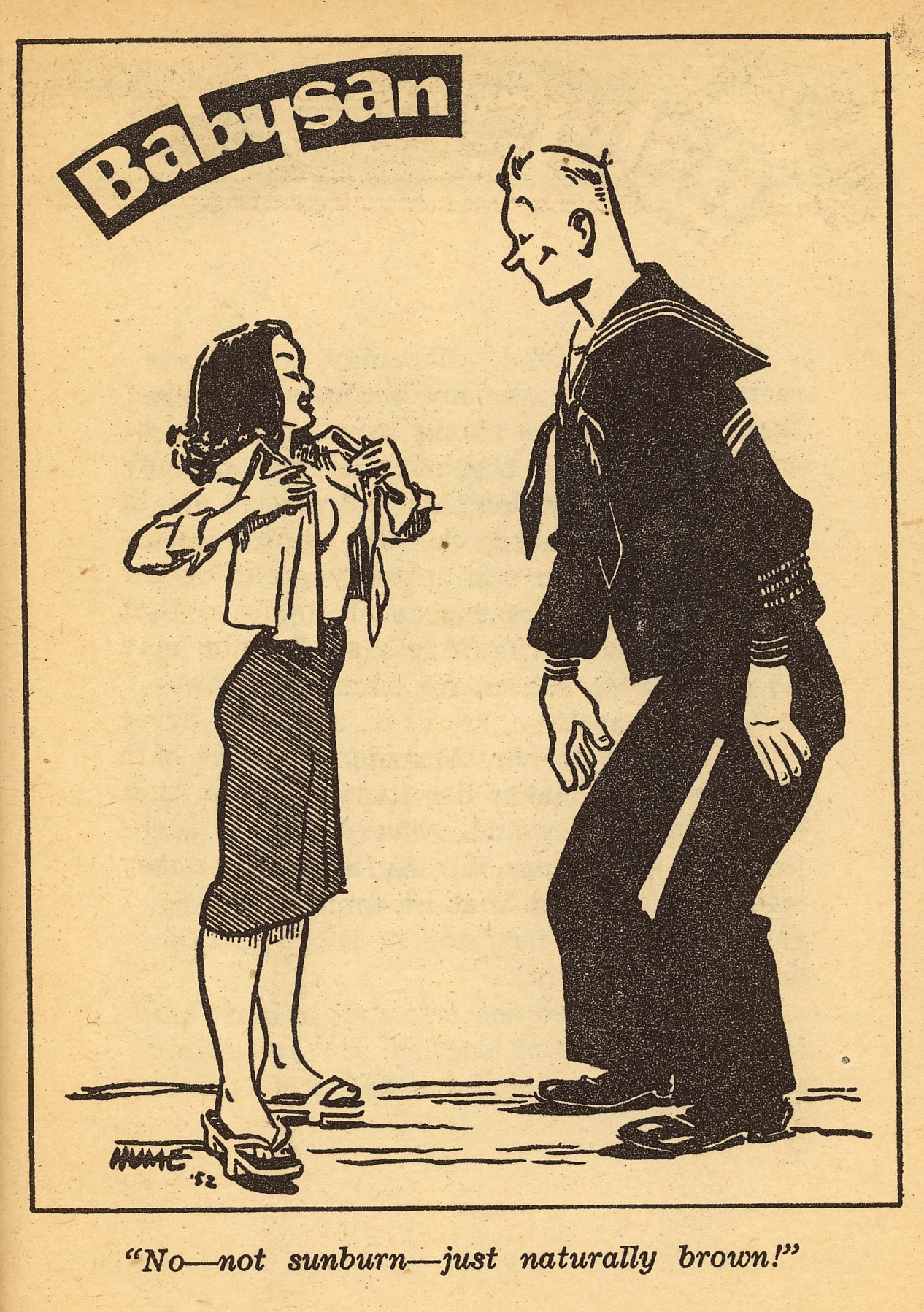

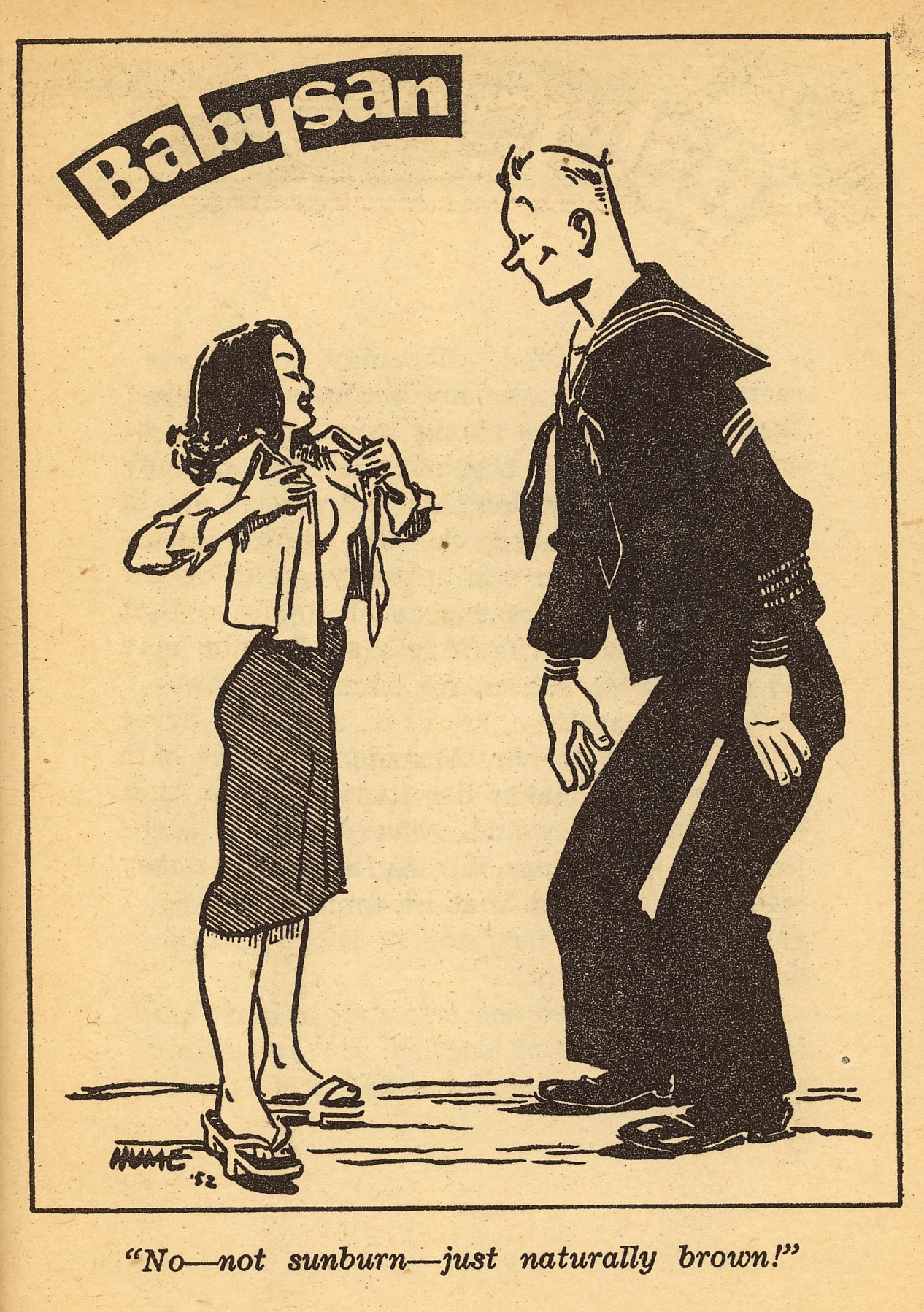

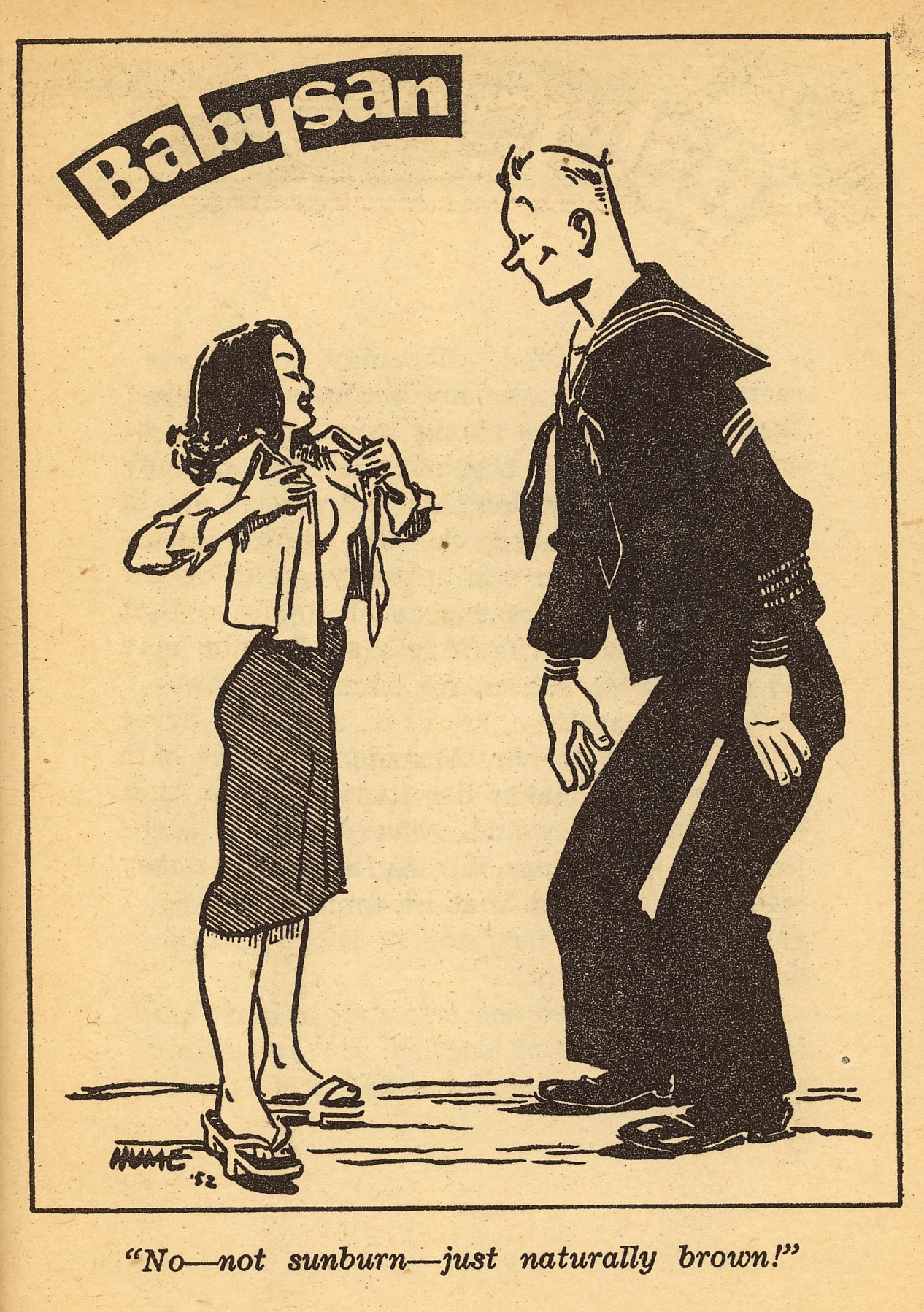

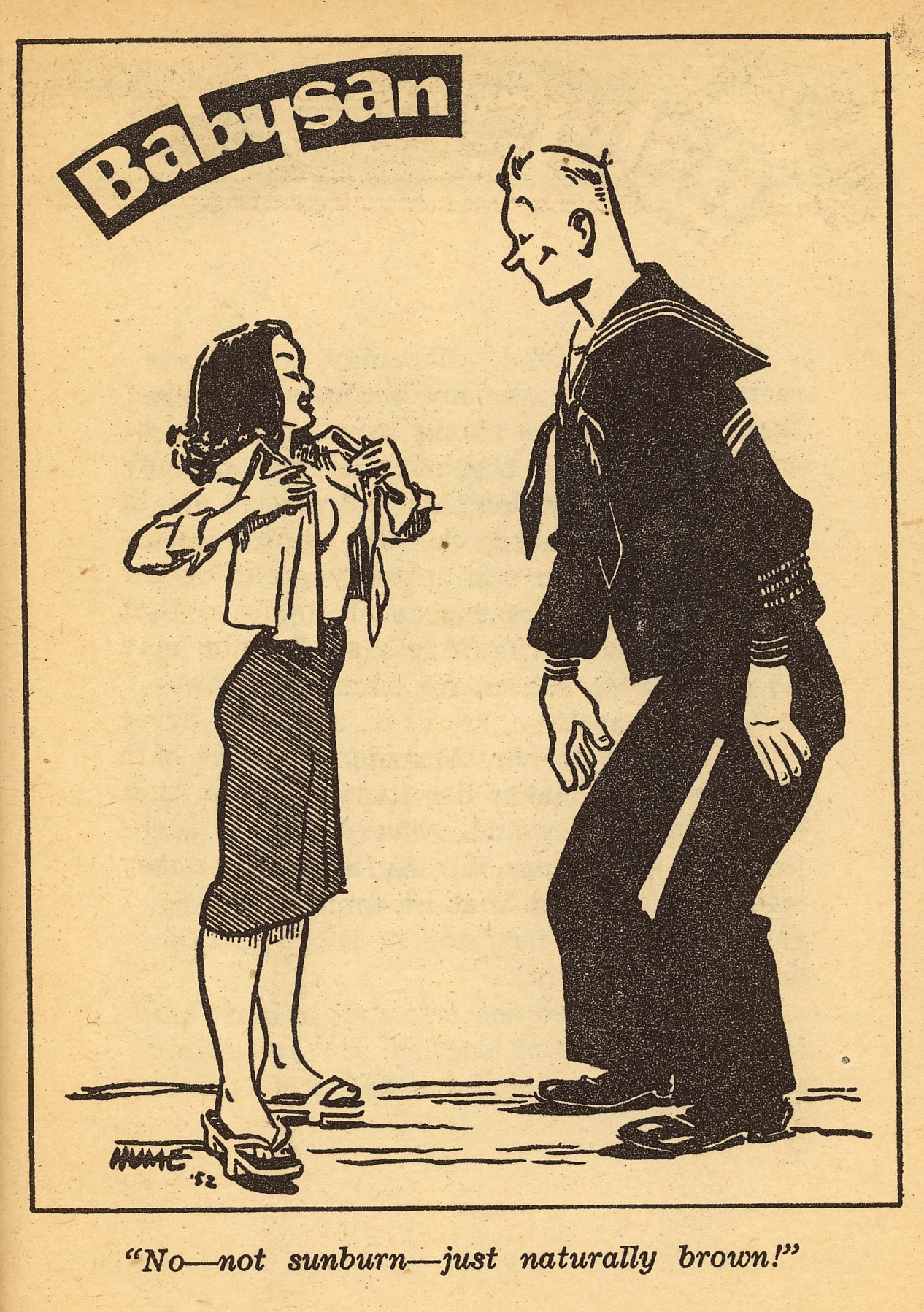

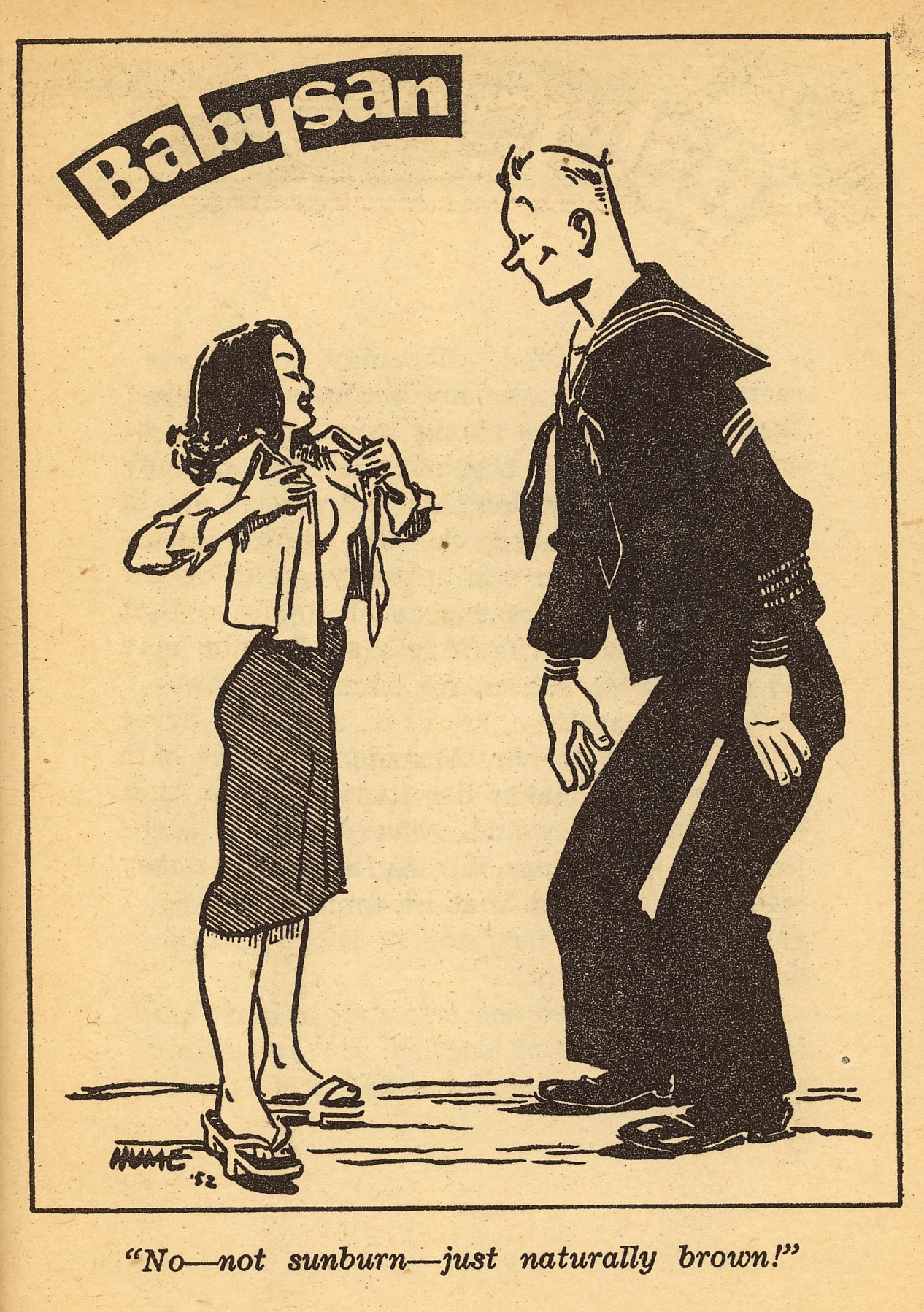

詢問文件或來源中缺少什麼內容與詢問其包含什麼內容一樣富有成效。在巴比桑中,有許多明顯的缺席或省略。 也許最引人注目的是,巴巴桑的社交世界極其簡單化和同質化,抑制了軍事基地內外實際存在的大部分多樣性。休謨所述的社會差異集中在年輕的日本女性和她們的美國男友之間的對立。這種差異是性別和文化的差異,而且顯然也是種族的差異,正如幾部探討膚色問題的漫畫所強調的。 “不——不是曬傷——只是自然的棕色!”是其中一張圖片的說明文字,其中巴比桑愉快地為一位凝視的水手打開她的襯衫 [巴比桑,84-85;另見 37]。[6] [圖4]

圖4

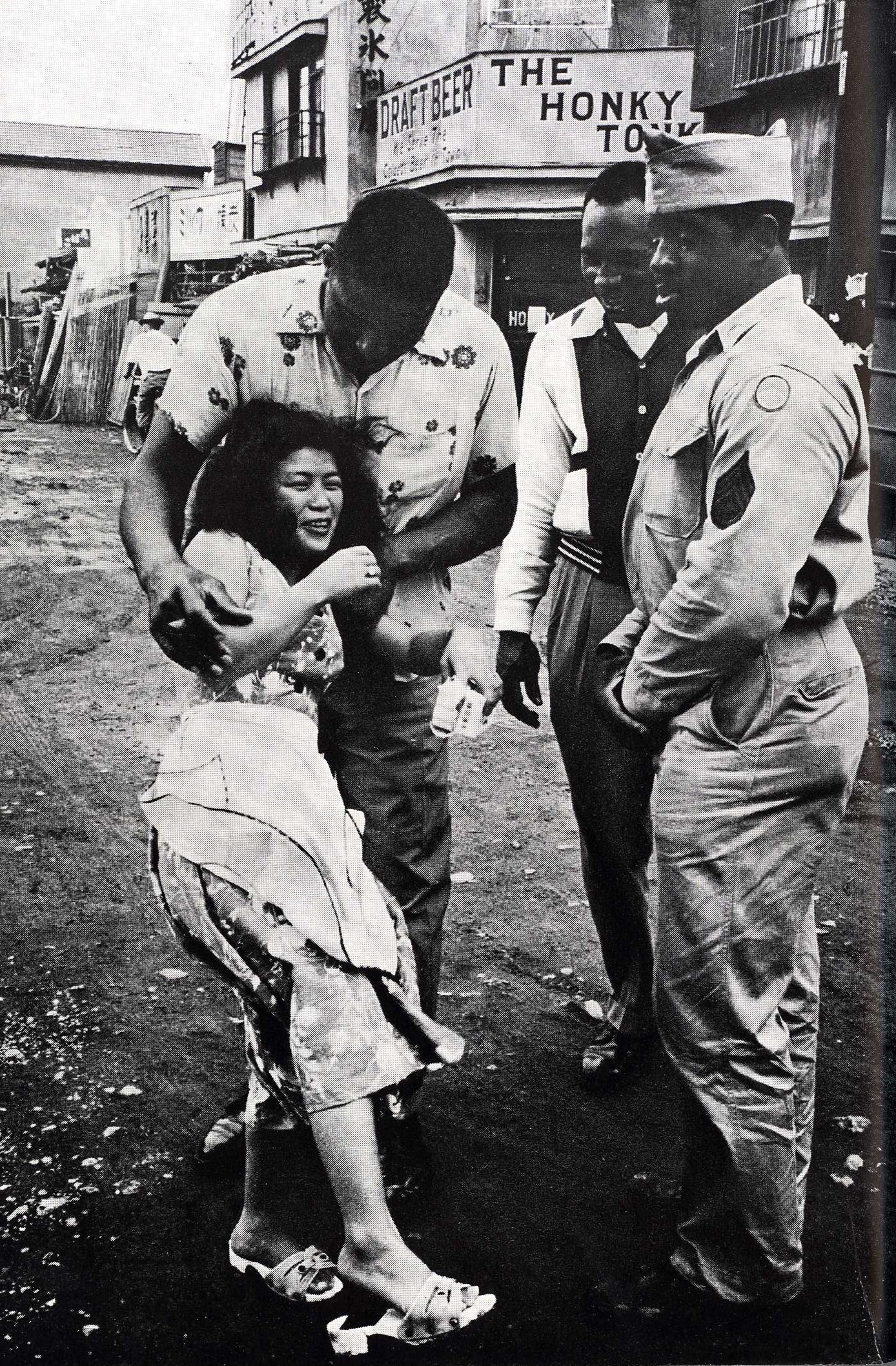

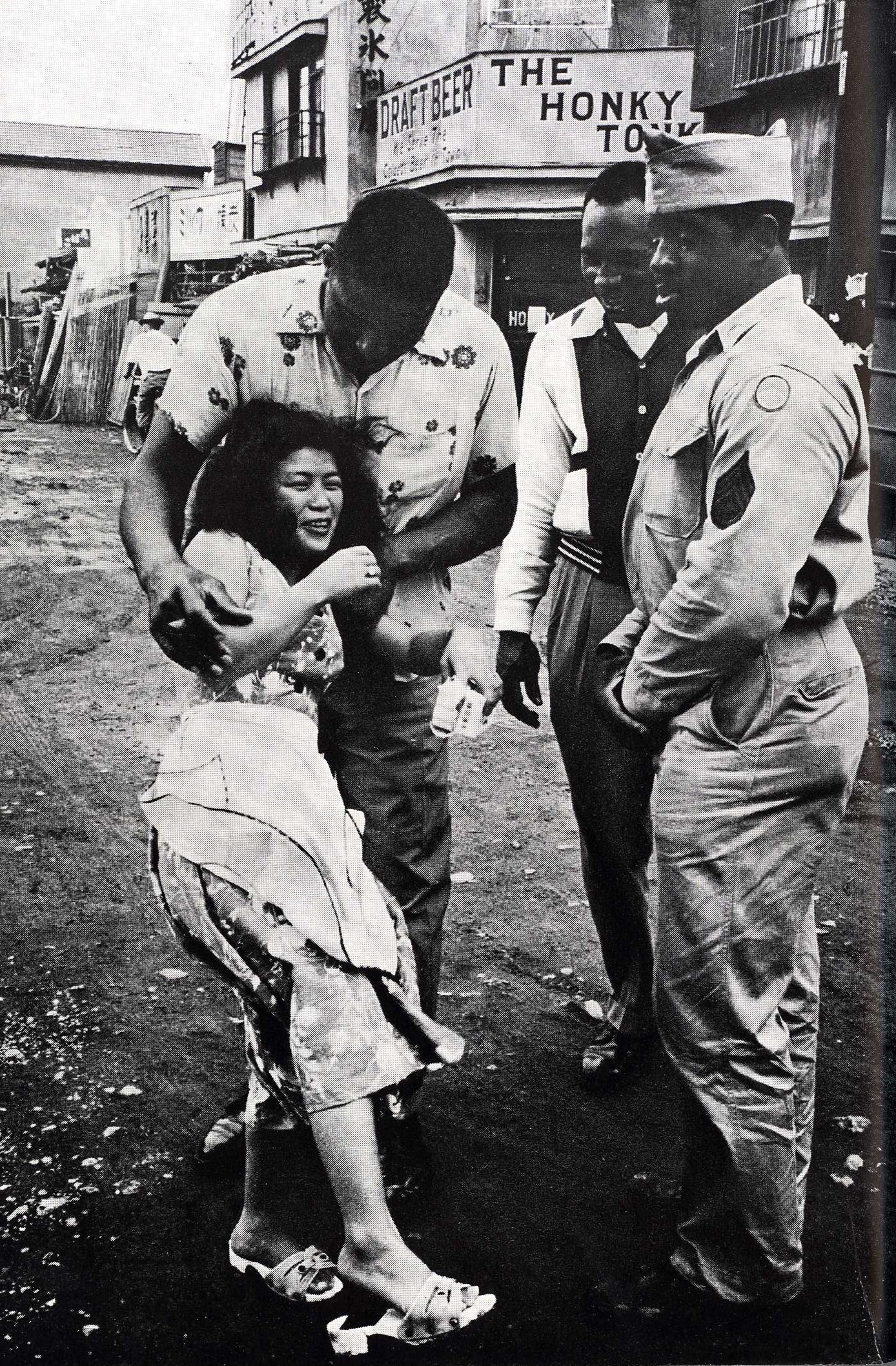

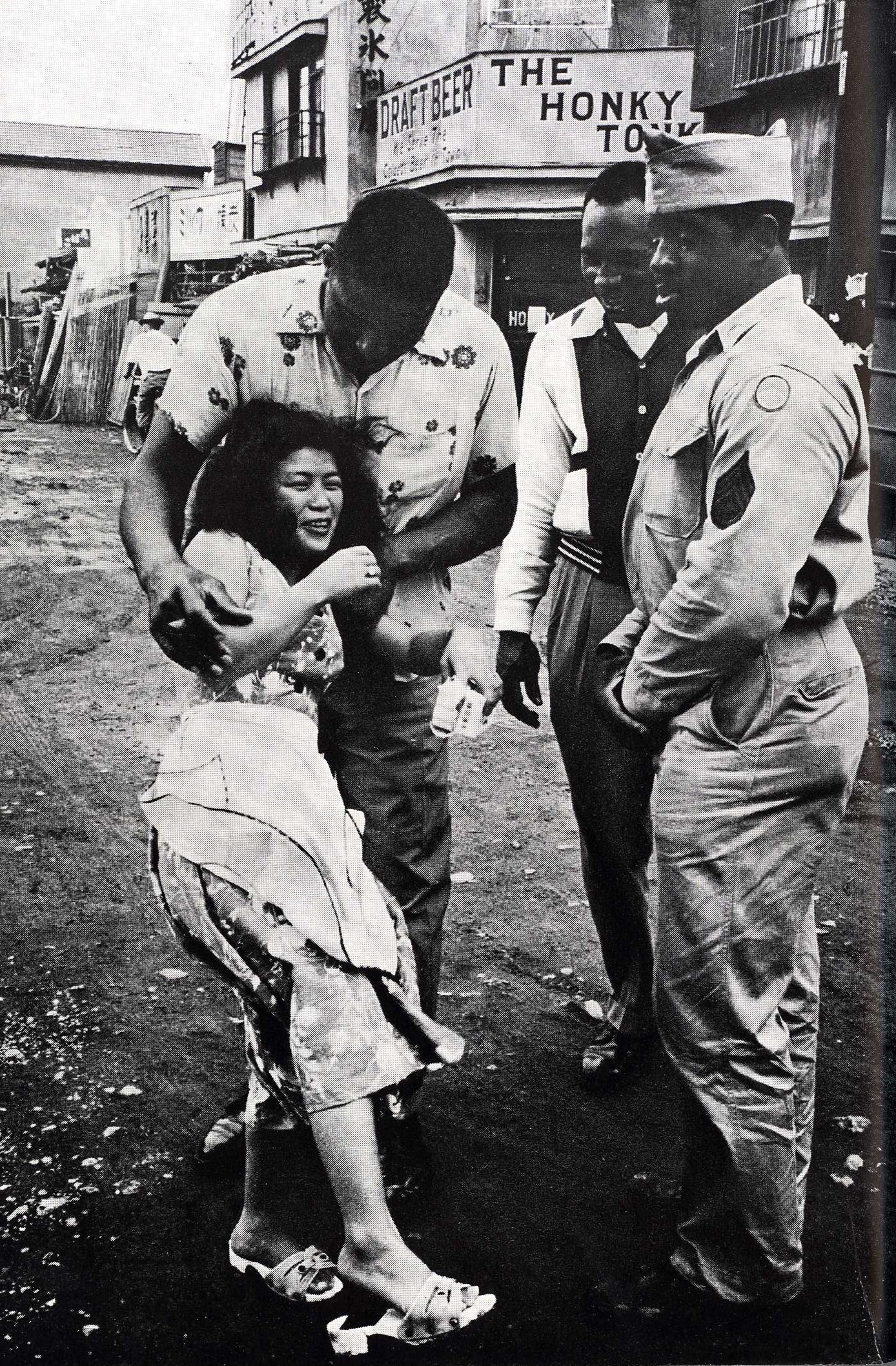

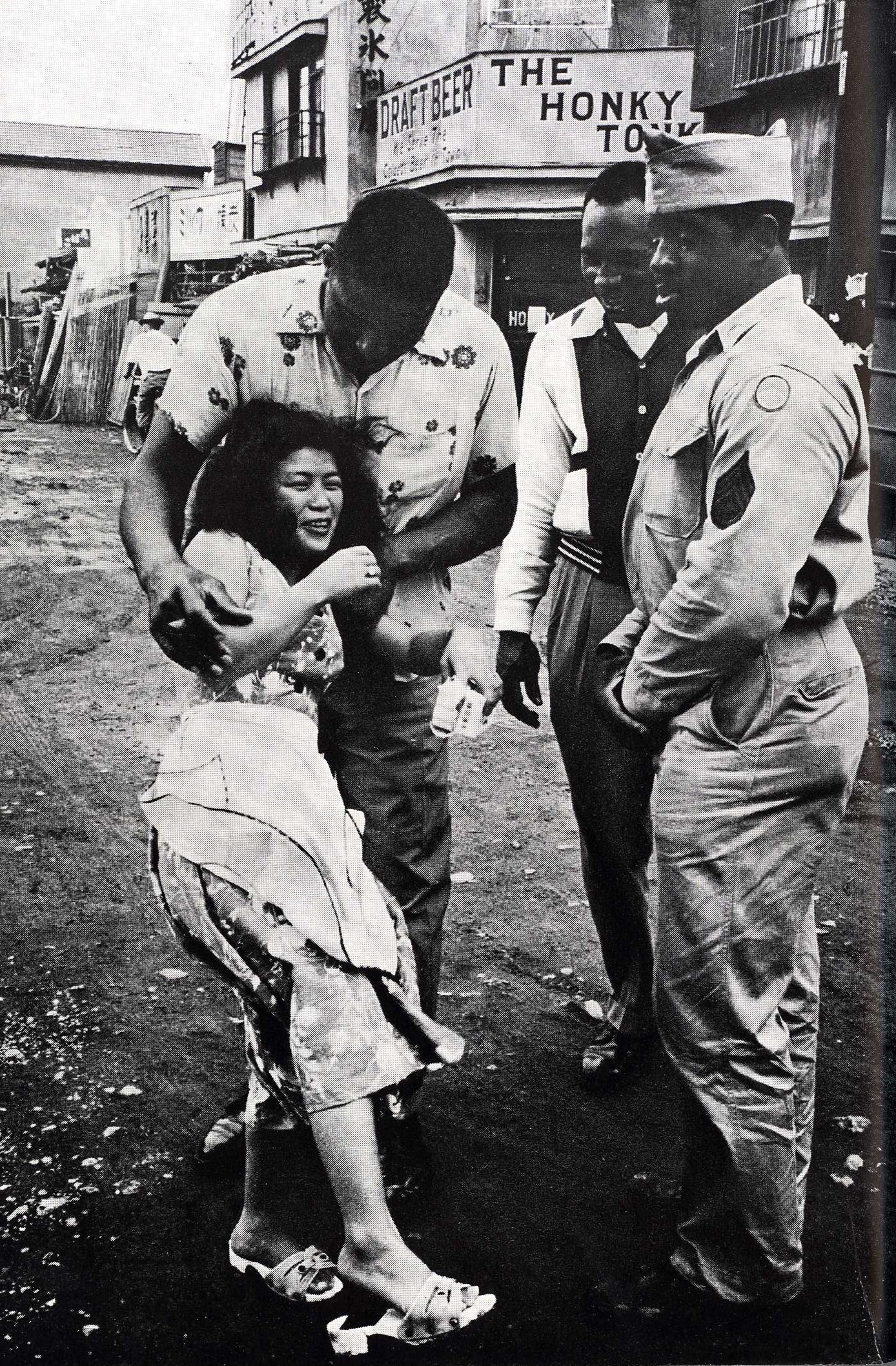

然而,巴巴桑關注的是白人士兵對日本女性「色彩繽紛」的身體的迷戀,掩蓋了一個事實,即並非所有盟軍都是白人。相當多的非裔美國人在佔領軍中服役,直到 1951 年為止,他們都被隔離在全黑人單位中,並在工作期間和下班時間都遭受歧視性政策和待遇。在被佔領的日本也很重要的是亞裔美國人,尤其是日裔美國人,無論男女。同樣,佔領日本的英聯邦軍隊中有印度人、尼泊爾人和毛利人的部隊。儘管有充足的證據表明日本士兵和非白人士兵之間存在社會互動,包括性關係,但巴比桑的佔領者完全是白人。[7] 納入非白人水手的代表可能會引入內部差異和不平等的分裂問題,這些問題會削弱休謨漫畫等軍事娛樂的幽默和「鼓舞士氣」的功能。 [圖5]

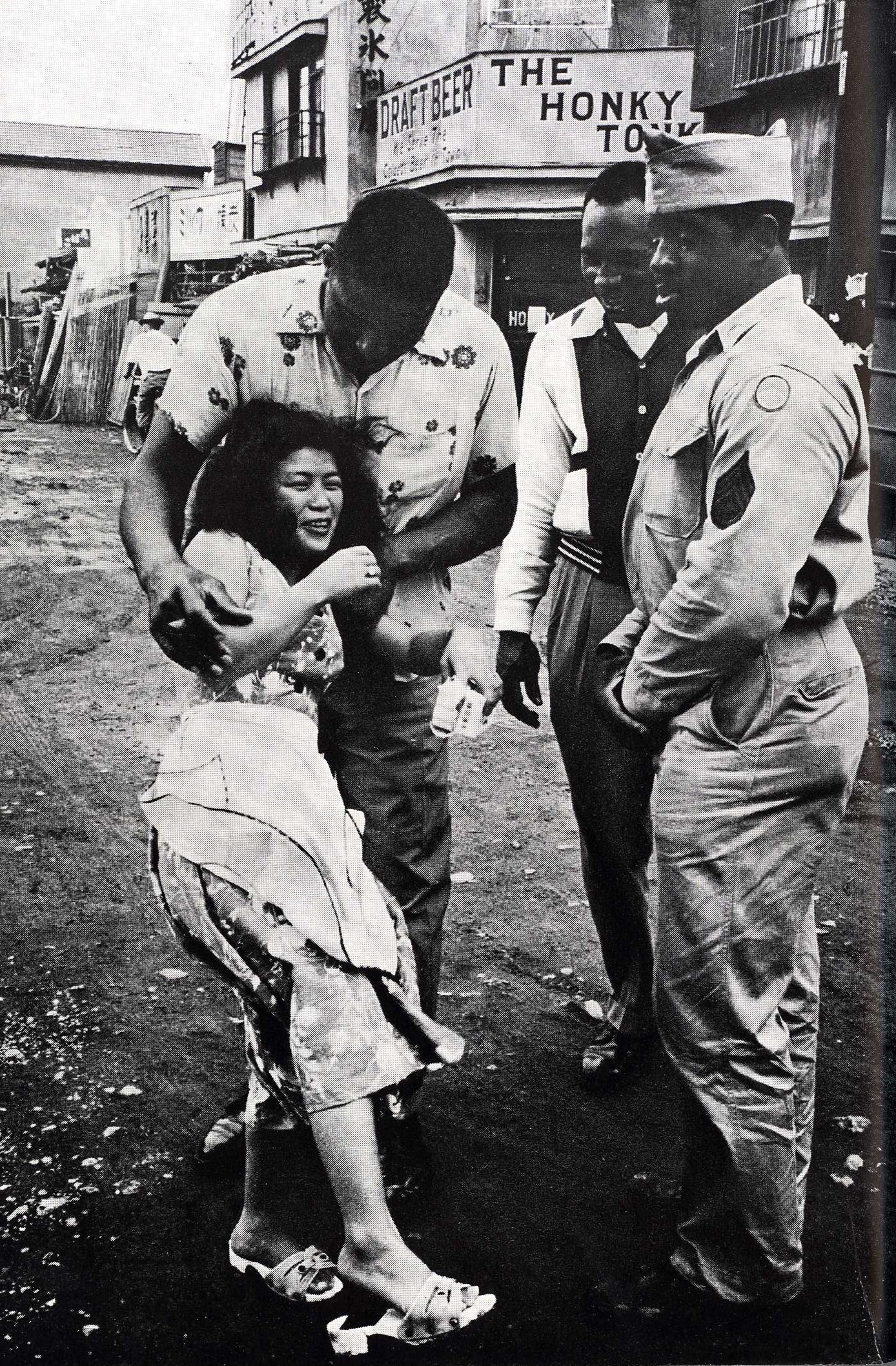

圖 5. 1957 年 Tokiwa Toyoko 在橫濱拍攝的非裔美國軍人和一名日本婦女的照片[8]

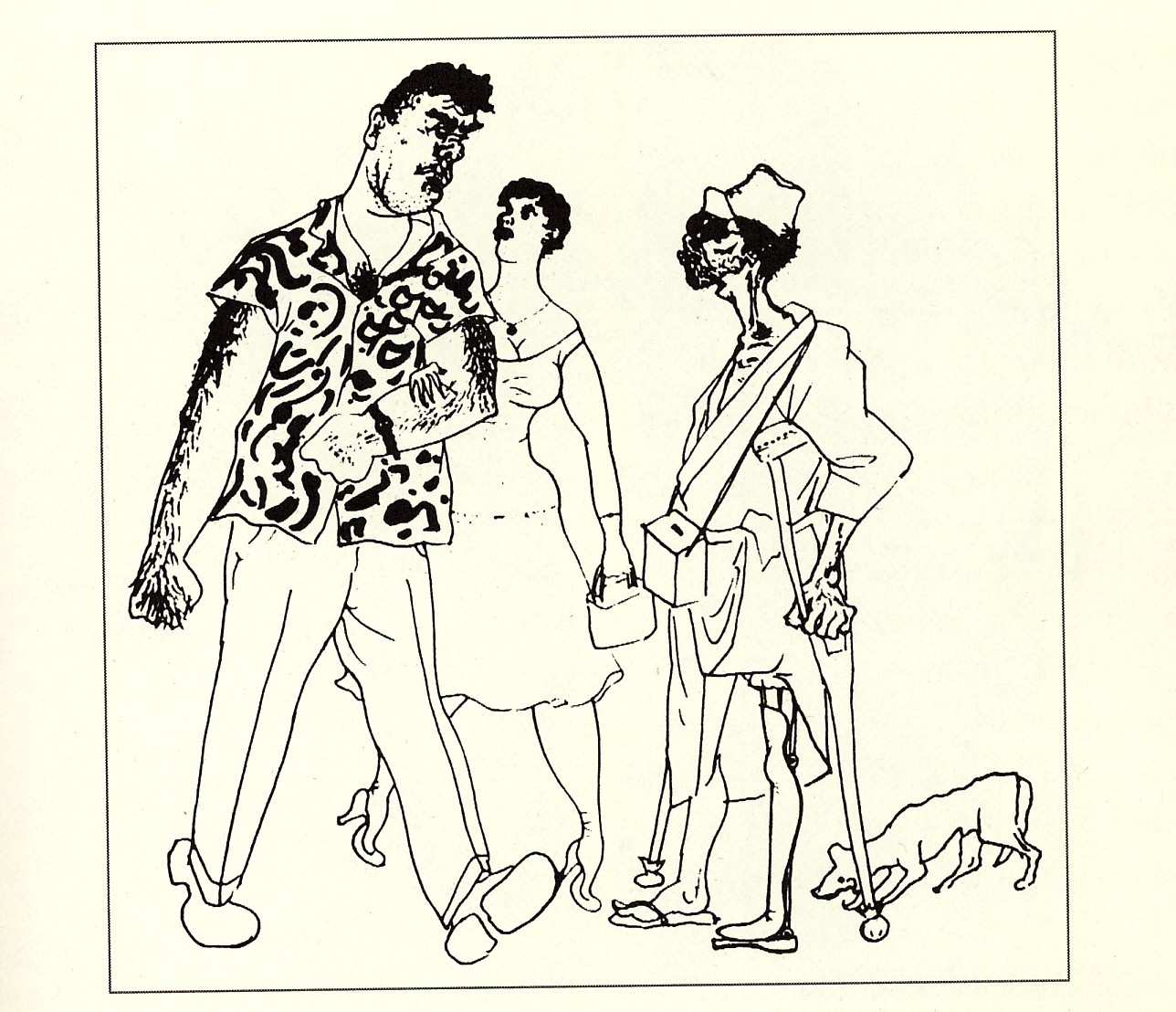

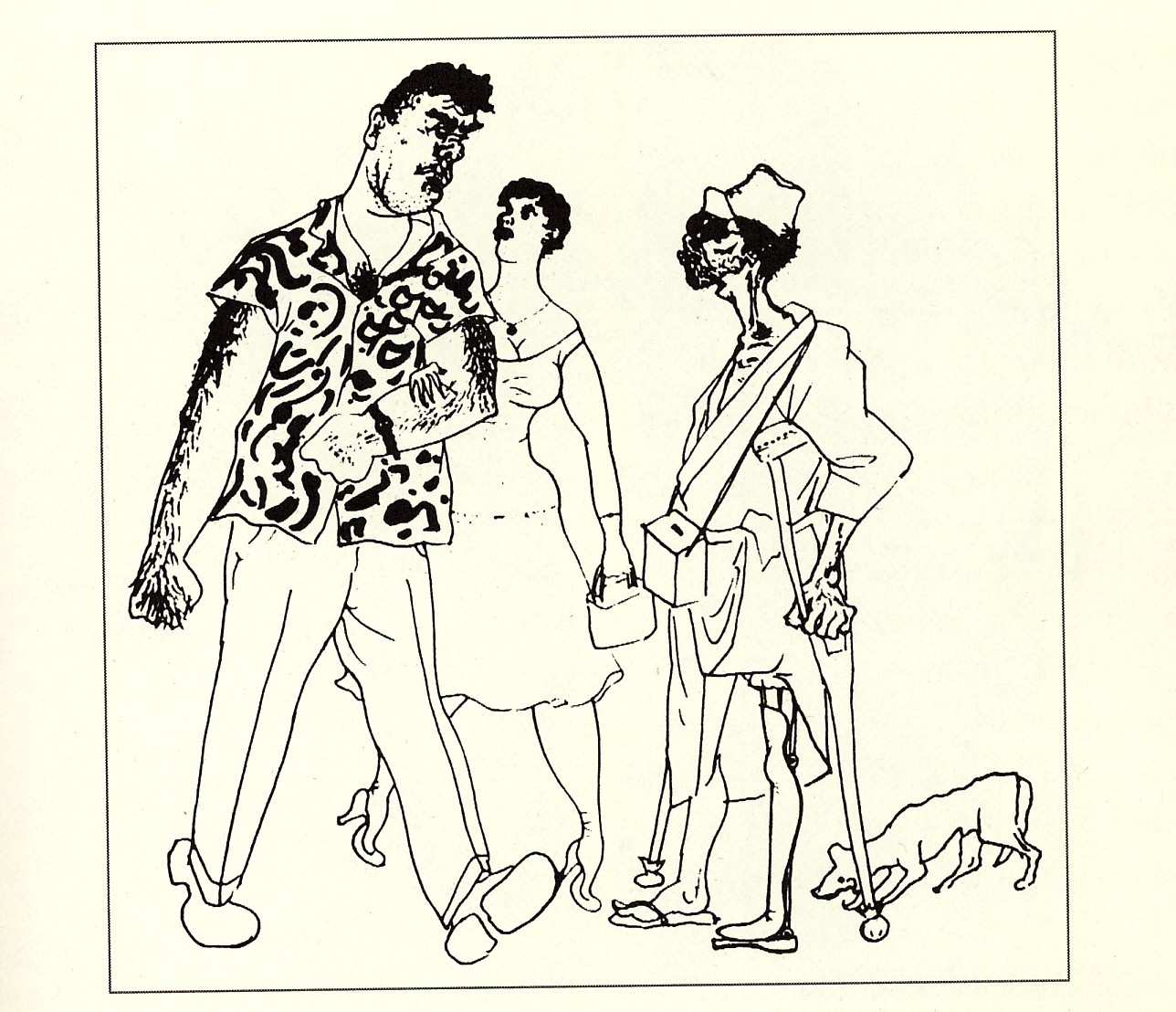

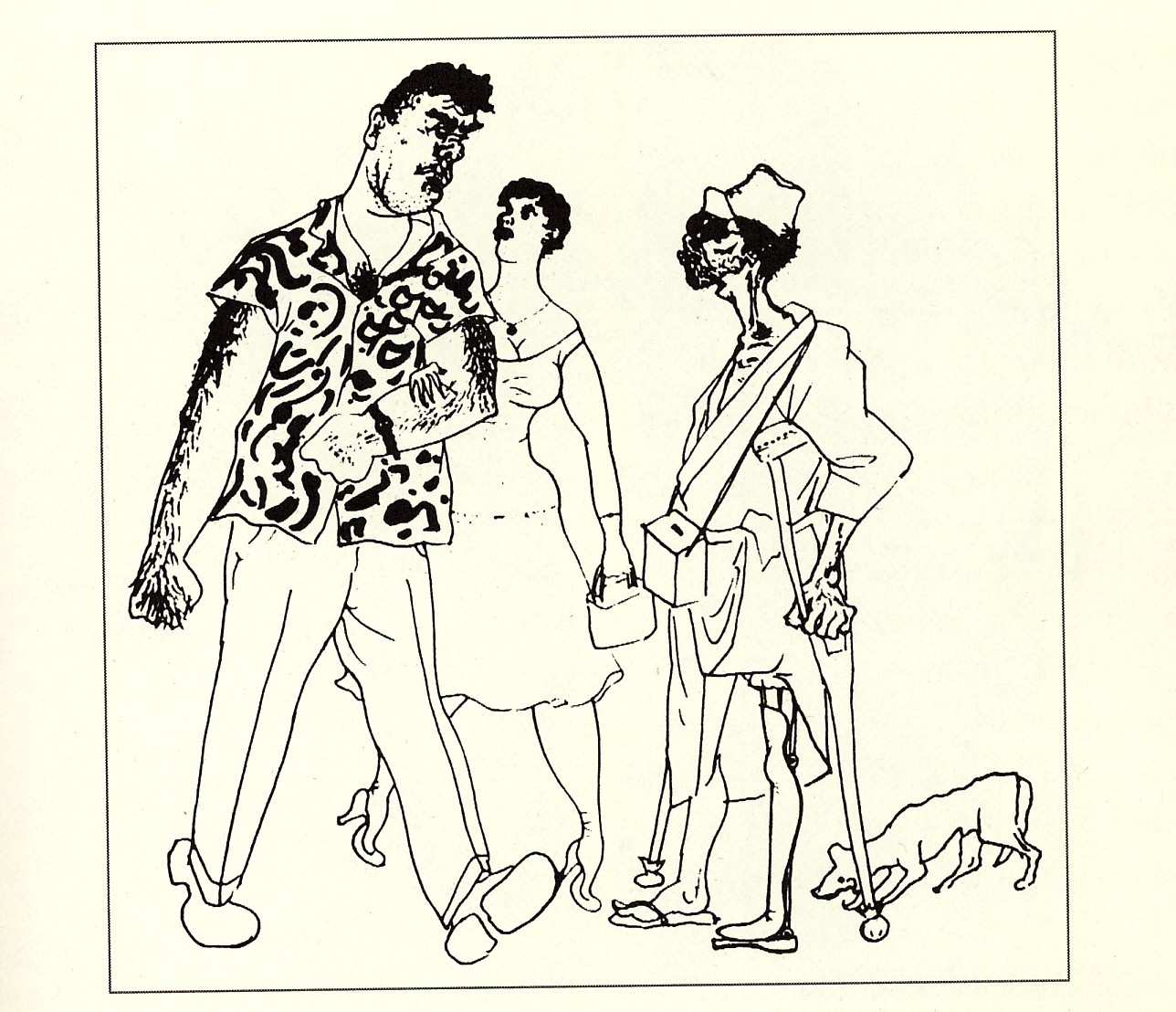

或許正是出於類似的邏輯,除了那些對軍事設施「蝴蝶結」的年輕女性之外,省略了對日本社會的任何提及。其他任何人的代表可能會讓觀眾想起其他部分的原住民,他們不太順從,甚至憎恨盟軍的存在。 [圖6]

圖 6. 圖片取自約翰·W·道爾 (John W. Dower),《擁抱失敗:二戰後的日本》,135。位殘疾的日本退伍軍人凝視著他的前敵人,一名正在享受戰爭的美國士兵。

在佔領期間及之後,日本社會的大部分人都對軍事基地、周圍的酒吧和妓院以及兩者的居民抱持懷疑、厭惡和憤怒的態度。除了代表外國軍事佔領的所有恥辱之外,對許多日本人來說,這些基地似乎不可避免地會用酒精和毒品、賣淫、暴力、賭博和黑市活動等有害混合物污染他們周圍的地區。事實上,自 1950 年代以來,日本團體一直持續進行社會活動,抗議美國軍事基地,並以各種方式傷害週邊社區。巴比桑

的另一個重要遺漏是佔領軍實際上與當地婦女進行了更廣泛的互動。例如,休謨選擇忽視普遍存在的普通賣淫,或經常發生的強姦和其他形式的性暴力,這並不奇怪。[9] 兩者都不符合美國軍隊的公眾形像或自我形象。然而,可能有點難以理解的是,巴比桑對持久關係導致婚姻的可能性保持沉默。相反,貫穿整個系列的基本假設是:「所有美好的事情都必須結束。男友與 Babysan 的交往也不例外」[ Babysan,120]。然而事實上,日本女性和她們的軍人男友之間的許多「交往」並沒有結束。早在 1947 年開始,越來越多的夫婦選擇結婚。據一位消息人士稱,到 1952 年底,已有超過 10,000 名美國人與日本女性結婚。這個數字在十年內只會成長。據估計,在 1950 年代和 1960 年代,與美國未婚夫或丈夫一起移民到美國的日本「戰爭新娘」人數高達 50,000 人。除此之外,還必須加上與盟軍士兵結婚但留在日本的人數,以及移民到英國和澳洲等其他國家的人數。[10]

巴比桑 忽視了美國軍人和日本女性之間非常真實且日益增長的婚姻現象,相反,他指出了 20 世紀 50 年代初圍繞這一話題的深深的不適。 如上所述,日本的官方軍事政策是阻止“親善”,儘管實際上它往往被視為必要的罪惡而被容忍。然而,直到1952 年美國移民法修改之前,美國人與日本國民之間的婚姻都被明確、正式禁止,理由是日本人在法律上無法進入美國。 ,日本人(以及中國人、印度人、菲律賓人和其他「東方人」)無法進入美國,因為他們的種族使他們沒有資格獲得公民身份。 即使在1952 年《麥卡倫沃爾特法案》通過後,為亞洲移民創造了有限的機會,將不同種族成員之間的婚姻(有時甚至是性關係)定為犯罪的「反混血」法律仍然有效,直到20 世紀60 年代,許多個人美國各州。因此,休謨堅持認為美國水手和日本女友之間的關係是無常的,這反映的並不是現實,而是聯邦、州和軍事法律的預期效果,以及支撐這些法律的緊張種族關係。[11]

三.巴比桑遊記

巴比桑也間接證明了日本以外的佔領所產生的深遠而持久的影響。例如,在 1940 年代末和 1950 年代,數以萬計的日本戰爭新娘移民到美國和其他盟國,這代表了美國和其他地方的一個重要的人口事件。事實上,在1924 年《排華法案》和1965 年《移民法案》之間的大約四十年間,亞洲人向美國移民的數量大幅減少,日本(和韓國)戰爭新娘實際上是唯一進入美國的亞洲人。 此外,這些亞洲移民中的大多數與白人結婚(儘管相當多的少數人與亞裔美國人和非裔美國人結婚),並成為混血美國兒童的母親,這一事實對種族隔離法構成了顯著挑戰和 20 世紀 50 年代美國的意識形態。美國主流社會接受日本和其他亞洲戰爭新娘的過程可以說是從像《寶貝桑》這樣的動畫片開始的,並延續到美國流行文化的其他產物,如流行歌曲、暢銷小說和大片。 。[12] 正如一位學者所指出的,美國大眾媒體對日本戰爭新娘及其與白人的「混血」婚姻進行了廣泛且日益積極的報道,這在一定程度上代表並掩蓋了更大、更棘手的問題即將到來的民權時代的黑人與白人種族關係。[13] [圖7]

圖 7. 《再見》海報(導演:約書亞洛根,1957 年)

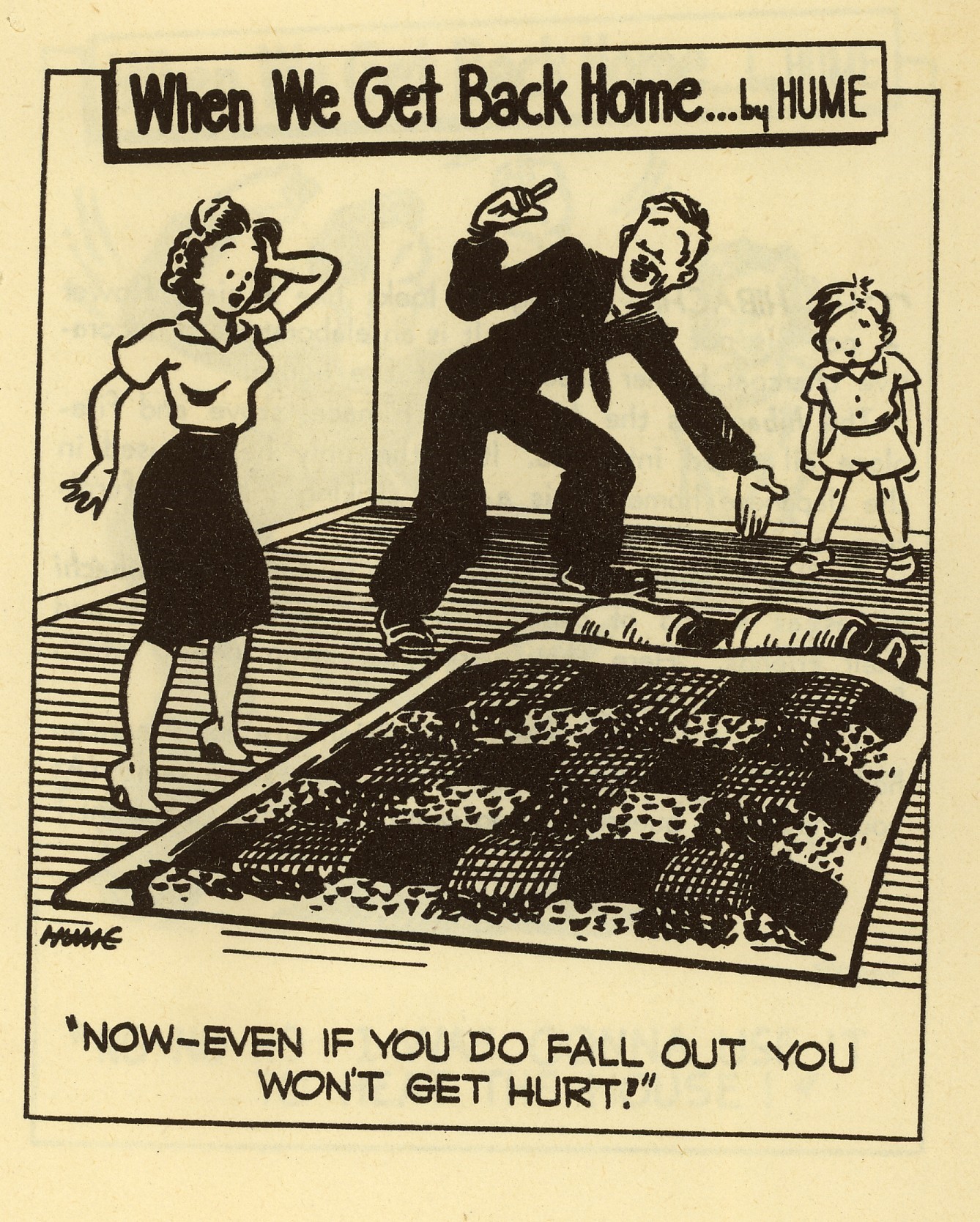

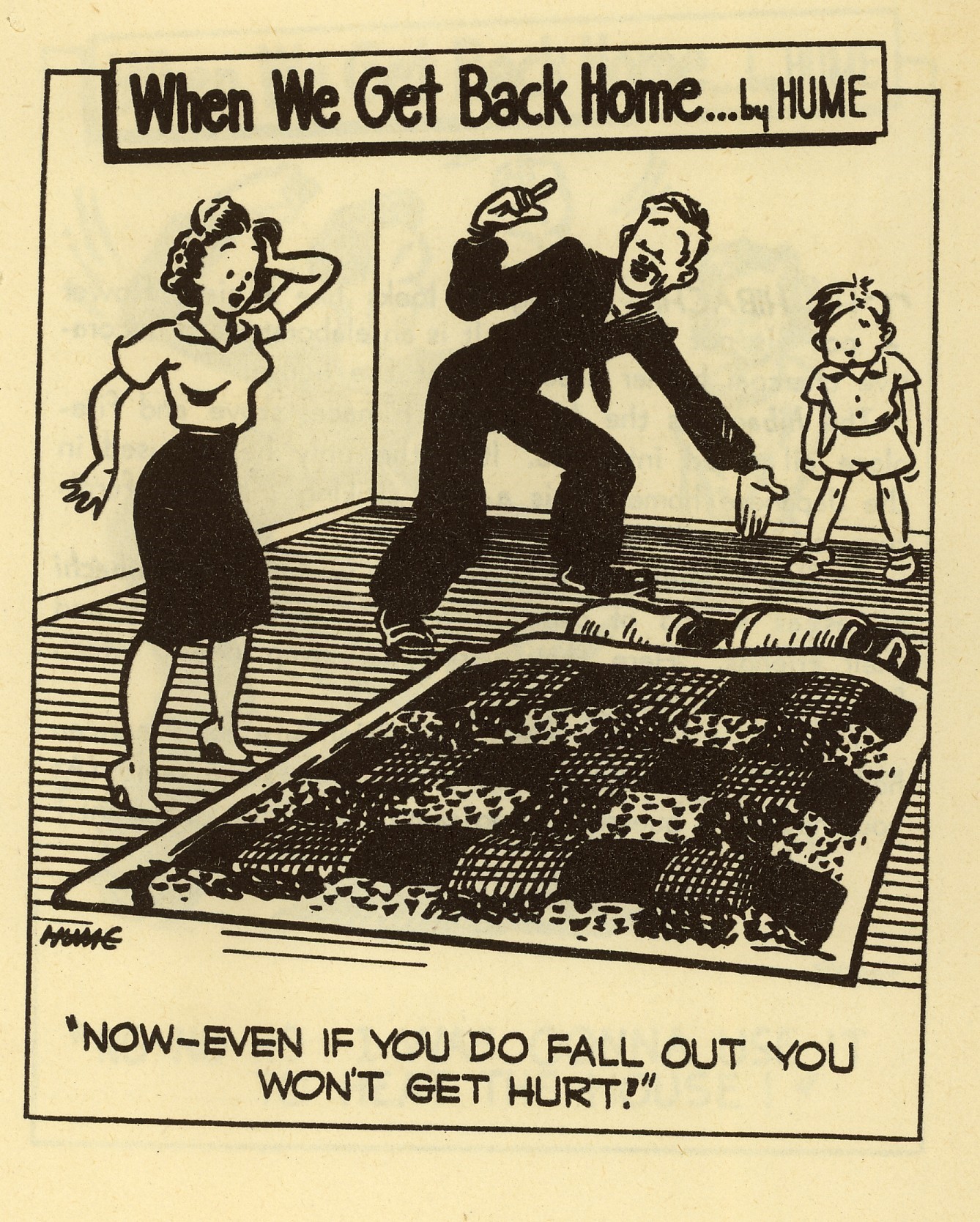

如上所述,巴比桑也表明,在日本人美國化的同時,美國人也可能出現無意的日本化。在休謨於 1953 年出版的另一本漫畫中,題為《當我們從日本回家時》中,反復出現的笑話是,被運回“美國本土”的水手們保留了他們在日本學到的一些習俗和品味。美國婦女困惑地看著她們的丈夫坐在地板上,拿起電話,說出“moshi moshi”,並試圖打開門,就像在滑動障子一樣[當我們從日本回家時,5, 113, 24 -25]。然而,20 世紀 50 年代確實見證了日本主題文化在美國日益流行——從電影、書籍、美食、時尚到建築和家居設計。 20 世紀 50 年代美國人對日本藝術和設計(包括障子等室內裝飾元素)興趣日益濃厚的原因很複雜,但職業經歷無疑是一個重要因素。[14] [圖8]

圖8

最後,還有另一個意義,可以說巴巴桑是「旅行」──也是堅持。休謨的漫畫生動地記錄了飽受戰爭蹂躪的東亞社會和廣闊的美國軍事設施交匯處所產生的許多習慣、習俗、態度和形象。雖然對日本的佔領於 1952 年正式結束,但在 20 世紀 50 年代及以後,數十萬年輕美國士兵繼續騎車進出美國在日本的大型永久軍事基地。 此外,美國在日本的基地與美國在亞洲其他地區的軍事介入密切相關。例如,在韓戰中,美國駐日本基地是美軍在半島作戰的主要集結地和庇護所。十年後,美國在菲律賓、韓國、台灣、關島、沖繩島以及日本的基地和設施進行了越戰。[15]舉一個巴比桑「旅行」方式的例子,「巴比桑」這個詞,就像許多其他在被佔領的日本首次流行的單字、短語和圖像一樣,在二戰期間繼續被美國軍隊使用。根據一本越南戰爭俚語詞典,“babysan”“在越南經常使用”,指的是“東亞孩子;一個年輕女子。[16] 因此,「巴比桑」文化的元素在龐大的美國太平洋司令部中得以延續和傳播——這是太平洋地區數百個軍事設施的龐大綜合體,這些設施將美國的力量投射到亞洲,最近投射到波斯灣和印度洋。其中許多設施,尤其是在沖繩和韓國,即使在今天,也被以亞洲年輕女性性勞動為中心的酒吧街區所包圍。[17]

總之,本文試圖提出幾種閱讀單一文獻資料的方法,以深入了解盟軍對日本的佔領以及日本、美國和東亞的戰後歷史。透過思考一位漫畫家對美國士兵和日本婦女之間互動的幽默描繪,我們可以加深對二十世紀世界歷史上的一個關鍵事件的理解,及其與當下的持續相關性。

[1]這些有關日本佔領軍的數字取自 Eiji Takamae, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 53-55, 125-135。

[2]有關美國在當今日本的軍事存在的資訊可以在 USFJ(美國軍隊,日本)的官方網站上找到:http://www.usfj.mil。

[3]比爾休謨 (Bill Hume) 與約翰安納裡諾 (John Annarino) 合著,《Babysan:私人審視日本佔領》(東京:Kasuga Boeki KK,1953 年)。

[4]關於賣淫與性行為,請參閱:John Dower,擁抱失敗:二戰後的日本(紐約:WW Norton and Co.,1999),第 4 章;武前,68-71;莎拉‧科夫納 (Sarah Kovner),《佔領權力:戰後日本的性工作者和軍人》(帕洛阿爾托:史丹佛大學出版社,2012 年)。

[5]關於佔領時期日本的流行音樂,請參閱 Michael K. Bourdaghs, Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), Chapter 1. 許多原創錄音以及更高版本可以在Youtube 上找到。例如,請參閱 Harry Belafonte 的幾張熱門歌曲“Gomen-nasai”的錄音。

[6]根據1950年代美國和其他地方盛行的種族分類,日本人和其他亞洲人的膚色是黃色的。雖然巴比桑強調日本女性是“有色人種”,但休謨避免將日本膚色描述為黃色,而是指其“棕色”。

[7]關於佔領日本的盟軍部隊的種族(和性別)多樣性,請參閱 Takemae,126-137。

[8] Tokiwa Toyoko,Kiken na adabana(東京:Mikasa shobô,1957),43。

[9]關於盟軍在日本實施的性暴力,請參閱 Takemae,67;科夫納,49-56。

[10] Anselm L. Strauss, “Strain and Harmony in American-Japan War-Bride Marriages,” Marriage and Family Living 16:2 (May 1954), 99-106引用了 1953 年 10,517 樁婚姻的數字。關於作為戰爭新娘移居美國的日本女性數量,請參閱:Bok-Lim C. Kim,“美國軍人的亞洲妻子:陰影中的女性”,Amerasia 4:1 (1977) 91-115; Rogelio Saenz、Sean-Shong Hwang、Benigno E. Aguirre,“尋找亞洲戰爭新娘”,人口統計31:3(1994 年 8 月),549-559。

[11]關於美國人與日本人之間的婚姻禁令,請參閱 Yukiko Koshiro,Trans-Pacific Racisms and the US Occupation of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 156-200。另請參閱:Susan Zeiger,《糾纏聯盟:二十世紀的外國戰爭新娘和美國士兵》(紐約:紐約大學出版社,2010 年),181-189。

[12]例如,1957 年的好萊塢電影《再見》由馬龍·白蘭度主演,飾演一位與真愛日本女子結婚的美國軍官。

[13]卡洛琳‧鐘‧辛普森(Caroline Chung Simpson),《缺席的存在:戰後美國文化中的日裔美國人,1945-1960》(達勒姆:杜克大學出版社,2001) ,第5章。

[14]有關 20 世紀 50 年代美國「日本繁榮」的進一步討論,請參閱 Brandt,《日本的文化奇蹟:重新思考世界強國的崛起,1945-1965 》 (即將出版,哥倫比亞大學出版社)。

[15]有關日本捲入越戰的討論,請參閱 Thomas RH Havens,《Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975》(普林斯頓:普林斯頓大學出版社,1987 年)。

[16] Tom Dalzell,《越戰俚語:歷史原則字典》,(紐約:Routledge,2014 年),5

[17] Saundra Pollock Sturdevant 和 Brenda Stoltzfus 的《Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the US Military in Asia》(紐約:The New Press,1992 年)對此主題進行了很好的介紹。

向巴比桑學習

1945 年 8 月 14 日,日本政府正式同意向二戰同盟國投降。不到兩週後,第一批美國軍隊開始在本州島主島的機場和港口登陸,開始盟軍佔領日本(1945-1952)。到 1945 年底,近 50 萬美國士兵駐紮在全國各地。 1946 年,英聯邦軍隊的另外 4 萬多名士兵(英國人、澳洲人、印度人和紐西蘭人)加入了他們的行列。

1946 年和 1947 年期間,駐日盟軍士兵數量急劇下降,因為很明顯,佔領軍基本上不會遭到反對,而且是和平的。儘管如此,在成立的七年裡,散佈在日本四個主要島嶼上的數十個基地駐紮著不少於 10 萬名軍事人員(其中大多數是 18 歲至 24 歲的男性)。 在韓戰期間(1951-1953),美國在日本的駐軍人數實際上再次增加,到1952年達到26萬名美國士兵 。結束佔領的談判包括日本和美國之間的雙邊安全條約,該條約規定美國軍事基地無限期繼續存在。如今,美國在日本仍有約85處軍事設施。大多數位於沖繩島,沖繩島是美軍控制的島嶼群,直到 1972 年回歸日本為止,但主要島嶼上仍然存在一些屬於美國海軍陸戰隊的重要基地(岩國、富士營)、空軍基地陸軍(橫田、三澤)、海軍(佐世保、橫須賀、厚木)、陸軍(座間)。[2]

數十萬(主要是美國士兵)不斷地騎自行車進出日本,對兩國和世界產生了巨大影響,至今仍在產生影響。雖然學者們研究了佔領的許多方面,但直到最近,這種趨勢主要集中在盟軍(主要是美國)的政策和利益如何影響日本,特別是日本精英:政治家、政策制定者的單向和自上而下的故事上。較新的研究探討了日本人自身在塑造職業中的積極作用,以及普通和精英日本人職業經歷中的一些更常見的方面。特別是後一個計畫的結果是,人們重新認識到盟軍士兵及其基地對日本日常生活的影響。 然而,仍然容易被忽視的是日本對其佔領者同樣深遠的影響。在日本完成服役的年輕的美國、澳洲和其他盟軍士兵也受到了他們的經歷的影響,他們在離開日本或進入軍事生涯的其他站點時將這些經歷帶回家。

特別是在美國流行文化中可以找到與美國大兵的經驗直接相關的易於取得的資料。本文探討了一個例子:由一名海軍軍人在佔領時期最後兩年繪製和撰寫的漫畫集,並於 1953 年在日本和美國以書名《Babysan:私人審視日本佔領》一書的形式重新出版。[3] 在以下各節中,我將提供一些建議,說明如何解讀《巴比桑》,作為深入了解日本、美國及其他地區的佔領者和被佔領者的佔領的一種手段。

I. Babysan 告訴我們什麼

《Babysan》 的主要作者比爾·休謨(Bill Hume,1916-2009 年)是來自密蘇裡州的海軍預備役軍人,1951 年應徵入伍,在日本厚木海軍空軍基地服役。休謨是平民生活中的商業藝術家,他開始在各種軍事期刊上發表有關美國士兵的漫畫,例如太平洋版的《星條旗》和《海軍時報》。 他最著名的漫畫涉及海軍軍人與年輕的日本女性(他稱她們為“Babysan”)的色情互動。休謨和他的合著者、海軍記者約翰·安納裡諾(John Annarino,1930-2009 年)在《Babysan》中解釋說,這個名字是美國和日本的混合體:

San可以被認為是先生、夫人、主人或小姐的意思。那麼,Babysan 可以直譯為「寶貝小姐」。美國人在街上看到一個陌生的女孩,不能只是大喊:“嘿,寶貝!”他在日本,禮貌是必需品而不是奢侈品,因此他巧妙地加上了「尊重」這個稱呼。它加快了介紹速度。 [巴比桑,16]

最直接的是,巴比桑讓我們深入了解美國士兵實際上如何對待日本平民的關鍵問題:佔領者與被佔領者之間關係的本質是什麼?例如,除了解釋「Babysan」一詞的起源之外,上面的引文還生動地描繪了佔領時代街道上常見的場景。盟軍士兵也不僅僅只是向日本婦女大聲問候。近年來,許多研究探討了日本被佔領期間,就像二戰後其他國家被佔領期間一樣,佔領軍和平民之間普遍存在性關係——或者軍方不贊成地稱之為“兄弟化”。 。 在佔領初期,日本政府為娛樂(和安撫)盟軍士兵而設立的妓院和其他設施中,有多達 70,000 名婦女在那裡賣淫。數以萬計的其他日本人在軍事設施內及其周圍以更隨意、私密的方式用性恩惠換取金錢或物品。然而《巴比桑》中描繪的女性並不完全是一個普通的性工作者——或者人們常說的「盼盼」 ——她們靠與軍人的短期性接觸為生。相反,休謨關注的是有時被稱為“ onrii”(來自“唯一”或“只有一個”)的灰色類別,即一次與“只有一個”穿制服的情人建立連續的、表面上一夫一妻制關係的女性,並獲得各種形式的物質補償作為回報。[4]

作為一部由美國軍人製作並為美國軍人製作的文件,《巴比桑》可能比它所描述的女性更多地揭示了他們的情況——但這裡對後者及其世界有真實的、有時是間接的洞察。例如,《巴巴桑》中的大部分幽默都源於美國水手對新女友的善意但常常天真的期望(忠誠、浪漫的依戀、經常發生性行為)與日本女人務實甚至欺騙性的決心之間的緊張關係。幾部漫畫指出,她聲稱自己有一個家庭需要養活,而她愛人的禮物對於他們以及她自己的生存都是必要的。 [圖1]

圖1

她的過去可能與許多其他女孩沒有太大不同。她的父親在戰爭中喪生,儘管她只是一個小女孩,但她必須工作來養家糊口。 。 。 。 年邁的母親正彎著腰在稻田裡工作。她的哥哥長大後想成為棒球運動員,但他當然是個體弱多病的孩子。巴比桑講述的關於她家人的故事有時令人難以置信。他們的體溫隨著巴比桑的經濟狀況而升降,這似乎有些不可思議。 [巴比桑,96]

作者對此表示懷疑,但日本的許多年輕女性,就像世界各地遭受戰爭蹂躪的國家一樣,確實發現自己陷入了這樣的困境,而一些人能夠獲得盟軍人員帶來的貨物和現金,這有助於支持在物質極度匱乏的時期,擴大家庭和他人的網絡。

同樣可信的還有巴比桑所揭示的美國和日本文化的混合體,這種混合體幾乎立即出現在軍人和土著婦女之間的接觸空間中。 「巴比桑」一詞,以及漫畫中出現的許多其他「Panglish」例子(以及「巴比桑」末尾的一個模擬有用的術語表中),證明了軍事佔領所釋放的語言創造力。正如幾幅漫畫以及書中的術語表所表明的那樣,日本女性用英語交流的能力是透過軍人熟悉某些日語術語和短語的方式來提高的[ Babysan , 89, 124-127]。由此產生的洋涇浜語並不是一種平等的混合體——權力不平衡不可避免地有利於英語——但這一現象暗示了佔領的影響可能包括某種程度的日本化,而不僅僅是單向的美國化或西方化。 [圖2]

圖2

同樣,也有一些文獻提到了另一種在佔領者和被佔領者接觸區蓬勃發展的混合文化形式:流行音樂。一幅漫畫描繪了巴比桑與一名水手「在俱樂部地板上跳來跳去」的情景。 [圖3]

圖3

隨附的文字將曲調標識為“日本倫巴”[ Babysan,10-11]。日本唱片公司 Nippon Columbia 於 1951 年發行的“日本倫巴”只是眾多熱門歌曲之一,例如“Tokyo Boogie Woogie”(1949 年)或“Gomen-nasai(請原諒我)”(1953 年)。或最近被佔領)的日本,並在日本及其以外的世界其他地區流通。[5]

二. Babysan 沒有告訴我們什麼

詢問文件或來源中缺少什麼內容與詢問其包含什麼內容一樣富有成效。在巴比桑中,有許多明顯的缺席或省略。 也許最引人注目的是,巴巴桑的社交世界極其簡單化和同質化,抑制了軍事基地內外實際存在的大部分多樣性。休謨所述的社會差異集中在年輕的日本女性和她們的美國男友之間的對立。這種差異是性別和文化的差異,而且顯然也是種族的差異,正如幾部探討膚色問題的漫畫所強調的。 “不——不是曬傷——只是自然的棕色!”是其中一張圖片的說明文字,其中巴比桑愉快地為一位凝視的水手打開她的襯衫 [巴比桑,84-85;另見 37]。[6] [圖4]

圖4

然而,巴巴桑關注的是白人士兵對日本女性「色彩繽紛」的身體的迷戀,掩蓋了一個事實,即並非所有盟軍都是白人。相當多的非裔美國人在佔領軍中服役,直到 1951 年為止,他們都被隔離在全黑人單位中,並在工作期間和下班時間都遭受歧視性政策和待遇。在被佔領的日本也很重要的是亞裔美國人,尤其是日裔美國人,無論男女。同樣,佔領日本的英聯邦軍隊中有印度人、尼泊爾人和毛利人的部隊。儘管有充足的證據表明日本士兵和非白人士兵之間存在社會互動,包括性關係,但巴比桑的佔領者完全是白人。[7] 納入非白人水手的代表可能會引入內部差異和不平等的分裂問題,這些問題會削弱休謨漫畫等軍事娛樂的幽默和「鼓舞士氣」的功能。 [圖5]

圖 5. 1957 年 Tokiwa Toyoko 在橫濱拍攝的非裔美國軍人和一名日本婦女的照片[8]

或許正是出於類似的邏輯,除了那些對軍事設施「蝴蝶結」的年輕女性之外,省略了對日本社會的任何提及。其他任何人的代表可能會讓觀眾想起其他部分的原住民,他們不太順從,甚至憎恨盟軍的存在。 [圖6]

圖 6. 圖片取自約翰·W·道爾 (John W. Dower),《擁抱失敗:二戰後的日本》,135。位殘疾的日本退伍軍人凝視著他的前敵人,一名正在享受戰爭的美國士兵。

在佔領期間及之後,日本社會的大部分人都對軍事基地、周圍的酒吧和妓院以及兩者的居民抱持懷疑、厭惡和憤怒的態度。除了代表外國軍事佔領的所有恥辱之外,對許多日本人來說,這些基地似乎不可避免地會用酒精和毒品、賣淫、暴力、賭博和黑市活動等有害混合物污染他們周圍的地區。事實上,自 1950 年代以來,日本團體一直持續進行社會活動,抗議美國軍事基地,並以各種方式傷害週邊社區。巴比桑

的另一個重要遺漏是佔領軍實際上與當地婦女進行了更廣泛的互動。例如,休謨選擇忽視普遍存在的普通賣淫,或經常發生的強姦和其他形式的性暴力,這並不奇怪。[9] 兩者都不符合美國軍隊的公眾形像或自我形象。然而,可能有點難以理解的是,巴比桑對持久關係導致婚姻的可能性保持沉默。相反,貫穿整個系列的基本假設是:「所有美好的事情都必須結束。男友與 Babysan 的交往也不例外」[ Babysan,120]。然而事實上,日本女性和她們的軍人男友之間的許多「交往」並沒有結束。早在 1947 年開始,越來越多的夫婦選擇結婚。據一位消息人士稱,到 1952 年底,已有超過 10,000 名美國人與日本女性結婚。這個數字在十年內只會成長。據估計,在 1950 年代和 1960 年代,與美國未婚夫或丈夫一起移民到美國的日本「戰爭新娘」人數高達 50,000 人。除此之外,還必須加上與盟軍士兵結婚但留在日本的人數,以及移民到英國和澳洲等其他國家的人數。[10]

巴比桑 忽視了美國軍人和日本女性之間非常真實且日益增長的婚姻現象,相反,他指出了 20 世紀 50 年代初圍繞這一話題的深深的不適。 如上所述,日本的官方軍事政策是阻止“親善”,儘管實際上它往往被視為必要的罪惡而被容忍。然而,直到1952 年美國移民法修改之前,美國人與日本國民之間的婚姻都被明確、正式禁止,理由是日本人在法律上無法進入美國。 ,日本人(以及中國人、印度人、菲律賓人和其他「東方人」)無法進入美國,因為他們的種族使他們沒有資格獲得公民身份。 即使在1952 年《麥卡倫沃爾特法案》通過後,為亞洲移民創造了有限的機會,將不同種族成員之間的婚姻(有時甚至是性關係)定為犯罪的「反混血」法律仍然有效,直到20 世紀60 年代,許多個人美國各州。因此,休謨堅持認為美國水手和日本女友之間的關係是無常的,這反映的並不是現實,而是聯邦、州和軍事法律的預期效果,以及支撐這些法律的緊張種族關係。[11]

三.巴比桑遊記

巴比桑也間接證明了日本以外的佔領所產生的深遠而持久的影響。例如,在 1940 年代末和 1950 年代,數以萬計的日本戰爭新娘移民到美國和其他盟國,這代表了美國和其他地方的一個重要的人口事件。事實上,在1924 年《排華法案》和1965 年《移民法案》之間的大約四十年間,亞洲人向美國移民的數量大幅減少,日本(和韓國)戰爭新娘實際上是唯一進入美國的亞洲人。 此外,這些亞洲移民中的大多數與白人結婚(儘管相當多的少數人與亞裔美國人和非裔美國人結婚),並成為混血美國兒童的母親,這一事實對種族隔離法構成了顯著挑戰和 20 世紀 50 年代美國的意識形態。美國主流社會接受日本和其他亞洲戰爭新娘的過程可以說是從像《寶貝桑》這樣的動畫片開始的,並延續到美國流行文化的其他產物,如流行歌曲、暢銷小說和大片。 。[12] 正如一位學者所指出的,美國大眾媒體對日本戰爭新娘及其與白人的「混血」婚姻進行了廣泛且日益積極的報道,這在一定程度上代表並掩蓋了更大、更棘手的問題即將到來的民權時代的黑人與白人種族關係。[13] [圖7]

圖 7. 《再見》海報(導演:約書亞洛根,1957 年)

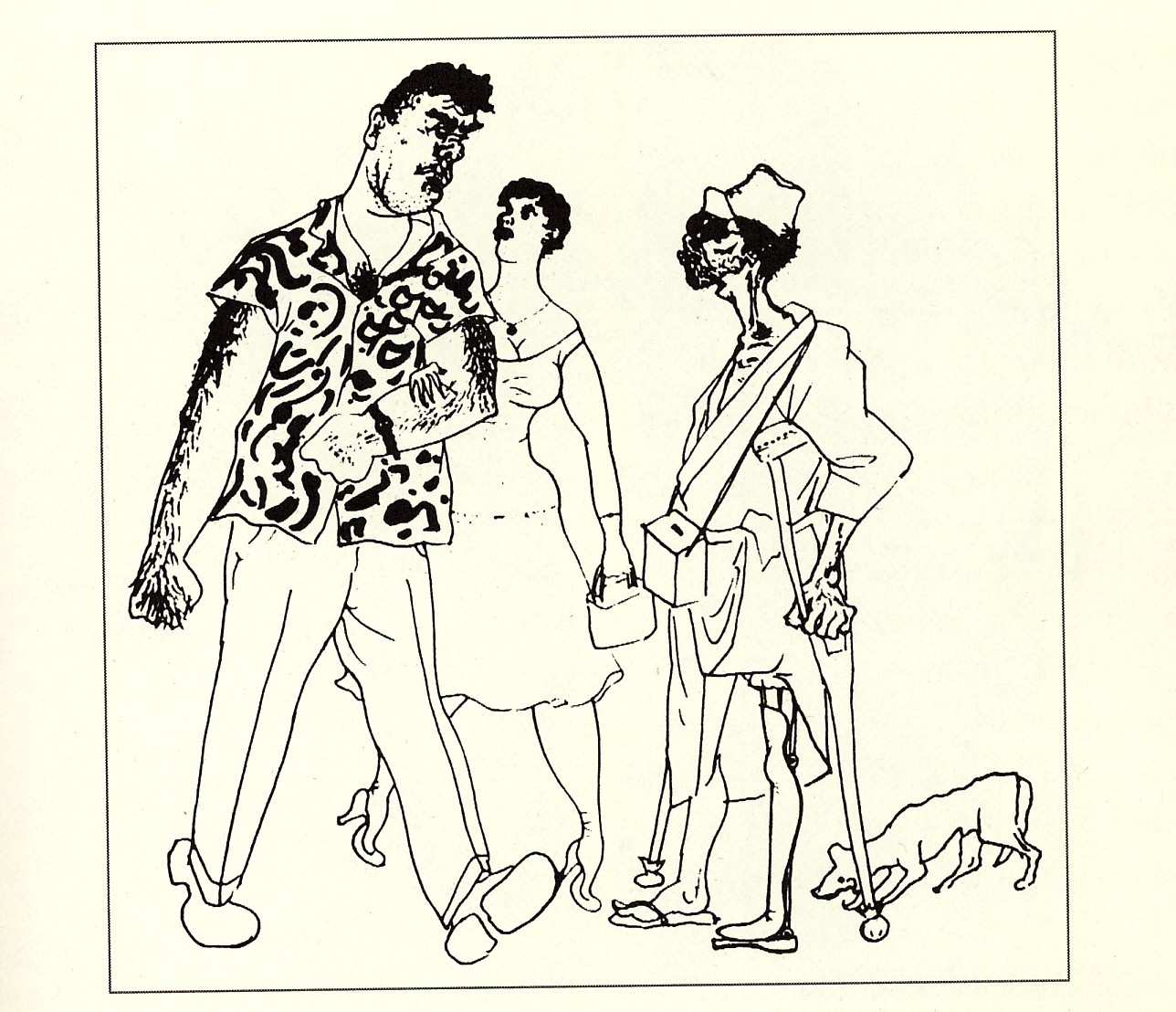

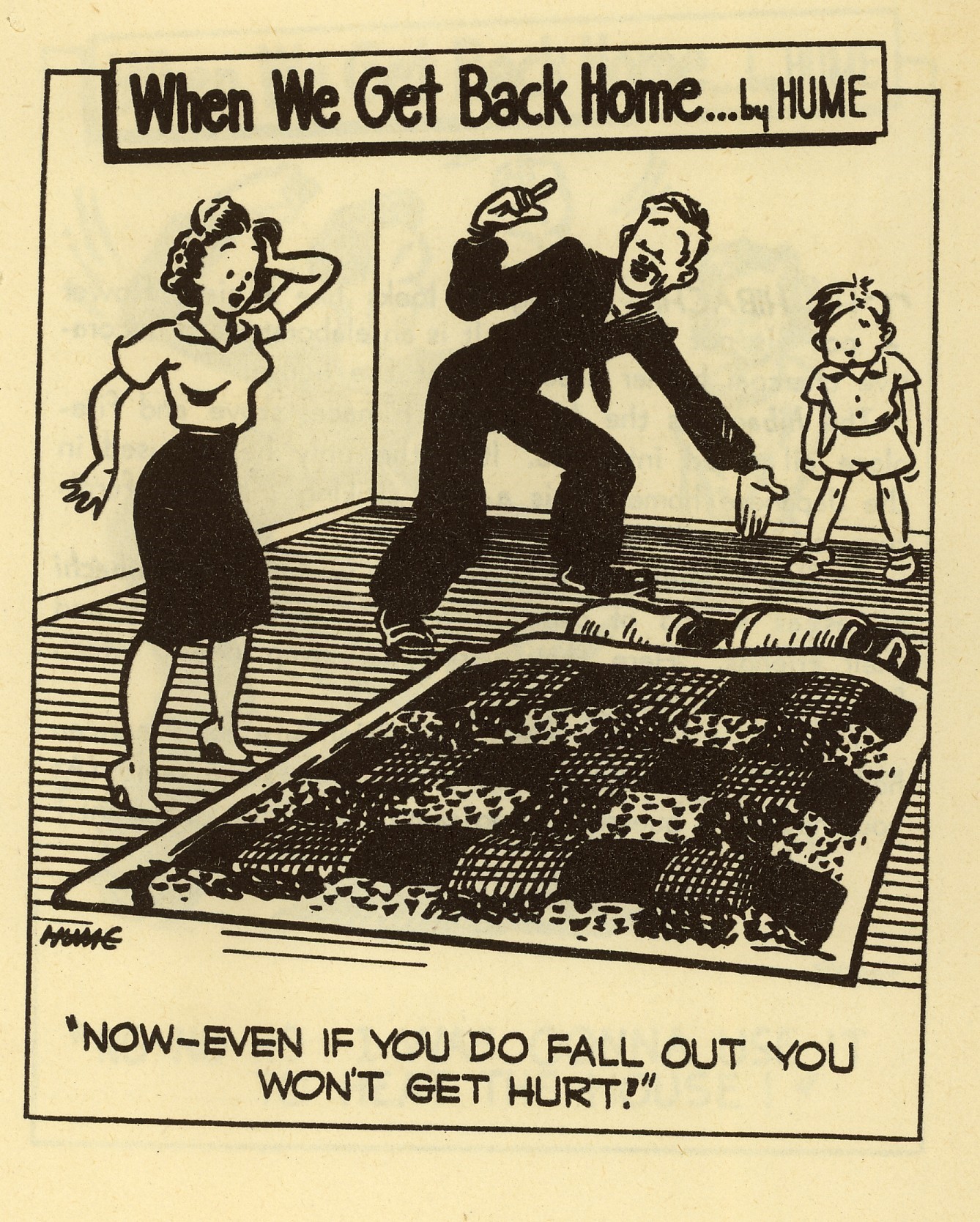

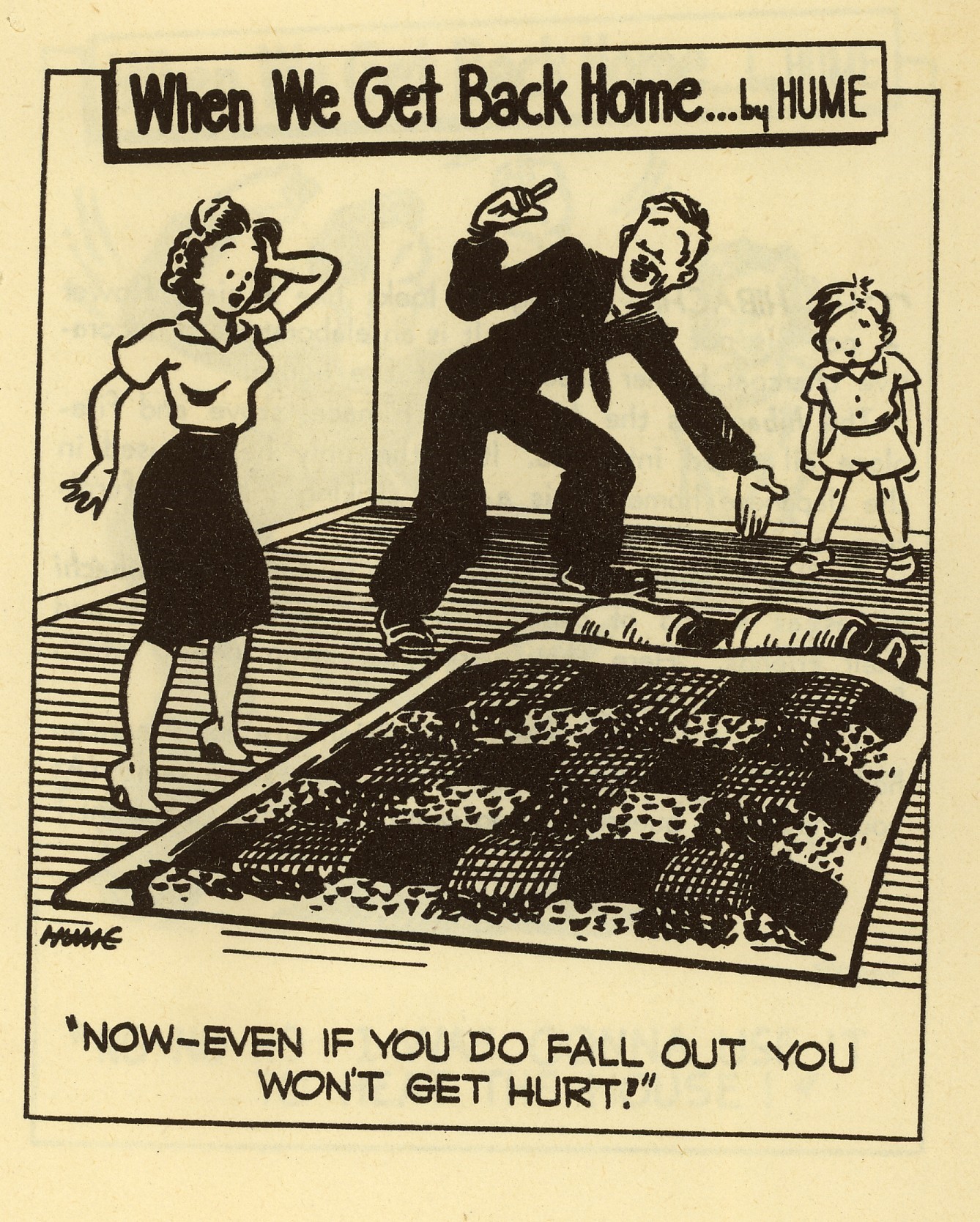

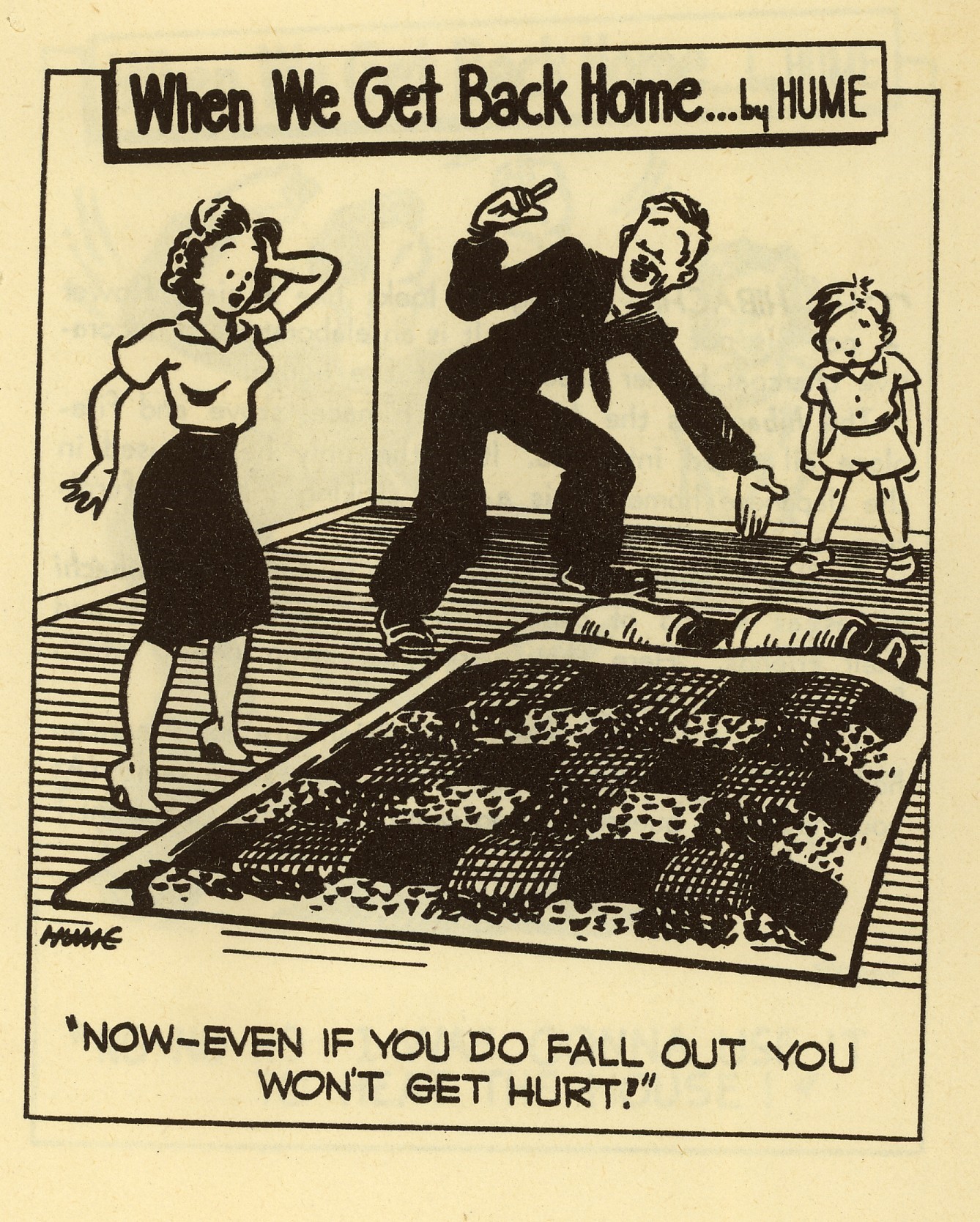

如上所述,巴比桑也表明,在日本人美國化的同時,美國人也可能出現無意的日本化。在休謨於 1953 年出版的另一本漫畫中,題為《當我們從日本回家時》中,反復出現的笑話是,被運回“美國本土”的水手們保留了他們在日本學到的一些習俗和品味。美國婦女困惑地看著她們的丈夫坐在地板上,拿起電話,說出“moshi moshi”,並試圖打開門,就像在滑動障子一樣[當我們從日本回家時,5, 113, 24 -25]。然而,20 世紀 50 年代確實見證了日本主題文化在美國日益流行——從電影、書籍、美食、時尚到建築和家居設計。 20 世紀 50 年代美國人對日本藝術和設計(包括障子等室內裝飾元素)興趣日益濃厚的原因很複雜,但職業經歷無疑是一個重要因素。[14] [圖8]

圖8

最後,還有另一個意義,可以說巴巴桑是「旅行」──也是堅持。休謨的漫畫生動地記錄了飽受戰爭蹂躪的東亞社會和廣闊的美國軍事設施交匯處所產生的許多習慣、習俗、態度和形象。雖然對日本的佔領於 1952 年正式結束,但在 20 世紀 50 年代及以後,數十萬年輕美國士兵繼續騎車進出美國在日本的大型永久軍事基地。 此外,美國在日本的基地與美國在亞洲其他地區的軍事介入密切相關。例如,在韓戰中,美國駐日本基地是美軍在半島作戰的主要集結地和庇護所。十年後,美國在菲律賓、韓國、台灣、關島、沖繩島以及日本的基地和設施進行了越戰。[15]舉一個巴比桑「旅行」方式的例子,「巴比桑」這個詞,就像許多其他在被佔領的日本首次流行的單字、短語和圖像一樣,在二戰期間繼續被美國軍隊使用。根據一本越南戰爭俚語詞典,“babysan”“在越南經常使用”,指的是“東亞孩子;一個年輕女子。[16] 因此,「巴比桑」文化的元素在龐大的美國太平洋司令部中得以延續和傳播——這是太平洋地區數百個軍事設施的龐大綜合體,這些設施將美國的力量投射到亞洲,最近投射到波斯灣和印度洋。其中許多設施,尤其是在沖繩和韓國,即使在今天,也被以亞洲年輕女性性勞動為中心的酒吧街區所包圍。[17]

總之,本文試圖提出幾種閱讀單一文獻資料的方法,以深入了解盟軍對日本的佔領以及日本、美國和東亞的戰後歷史。透過思考一位漫畫家對美國士兵和日本婦女之間互動的幽默描繪,我們可以加深對二十世紀世界歷史上的一個關鍵事件的理解,及其與當下的持續相關性。

[1]這些有關日本佔領軍的數字取自 Eiji Takamae, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 53-55, 125-135。

[2]有關美國在當今日本的軍事存在的資訊可以在 USFJ(美國軍隊,日本)的官方網站上找到:http://www.usfj.mil。

[3]比爾休謨 (Bill Hume) 與約翰安納裡諾 (John Annarino) 合著,《Babysan:私人審視日本佔領》(東京:Kasuga Boeki KK,1953 年)。

[4]關於賣淫與性行為,請參閱:John Dower,擁抱失敗:二戰後的日本(紐約:WW Norton and Co.,1999),第 4 章;武前,68-71;莎拉‧科夫納 (Sarah Kovner),《佔領權力:戰後日本的性工作者和軍人》(帕洛阿爾托:史丹佛大學出版社,2012 年)。

[5]關於佔領時期日本的流行音樂,請參閱 Michael K. Bourdaghs, Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), Chapter 1. 許多原創錄音以及更高版本可以在Youtube 上找到。例如,請參閱 Harry Belafonte 的幾張熱門歌曲“Gomen-nasai”的錄音。

[6]根據1950年代美國和其他地方盛行的種族分類,日本人和其他亞洲人的膚色是黃色的。雖然巴比桑強調日本女性是“有色人種”,但休謨避免將日本膚色描述為黃色,而是指其“棕色”。

[7]關於佔領日本的盟軍部隊的種族(和性別)多樣性,請參閱 Takemae,126-137。

[8] Tokiwa Toyoko,Kiken na adabana(東京:Mikasa shobô,1957),43。

[9]關於盟軍在日本實施的性暴力,請參閱 Takemae,67;科夫納,49-56。

[10] Anselm L. Strauss, “Strain and Harmony in American-Japan War-Bride Marriages,” Marriage and Family Living 16:2 (May 1954), 99-106引用了 1953 年 10,517 樁婚姻的數字。關於作為戰爭新娘移居美國的日本女性數量,請參閱:Bok-Lim C. Kim,“美國軍人的亞洲妻子:陰影中的女性”,Amerasia 4:1 (1977) 91-115; Rogelio Saenz、Sean-Shong Hwang、Benigno E. Aguirre,“尋找亞洲戰爭新娘”,人口統計31:3(1994 年 8 月),549-559。

[11]關於美國人與日本人之間的婚姻禁令,請參閱 Yukiko Koshiro,Trans-Pacific Racisms and the US Occupation of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 156-200。另請參閱:Susan Zeiger,《糾纏聯盟:二十世紀的外國戰爭新娘和美國士兵》(紐約:紐約大學出版社,2010 年),181-189。

[12]例如,1957 年的好萊塢電影《再見》由馬龍·白蘭度主演,飾演一位與真愛日本女子結婚的美國軍官。

[13]卡洛琳‧鐘‧辛普森(Caroline Chung Simpson),《缺席的存在:戰後美國文化中的日裔美國人,1945-1960》(達勒姆:杜克大學出版社,2001) ,第5章。

[14]有關 20 世紀 50 年代美國「日本繁榮」的進一步討論,請參閱 Brandt,《日本的文化奇蹟:重新思考世界強國的崛起,1945-1965 》 (即將出版,哥倫比亞大學出版社)。

[15]有關日本捲入越戰的討論,請參閱 Thomas RH Havens,《Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975》(普林斯頓:普林斯頓大學出版社,1987 年)。

[16] Tom Dalzell,《越戰俚語:歷史原則字典》,(紐約:Routledge,2014 年),5

[17] Saundra Pollock Sturdevant 和 Brenda Stoltzfus 的《Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the US Military in Asia》(紐約:The New Press,1992 年)對此主題進行了很好的介紹。

Learning from Babysan

The Japanese government formally agreed to surrender to the Allied nations of World War II on August 14, 1945. Famously, at noon on the following day Emperor Hirohito’s taped announcement of surrender was broadcast to the nation by radio. Less than two weeks later, the first United States troops started to land at airfields and ports on the main island of Honshu, to begin the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945-1952). By the end of 1945, nearly half a million American soldiers were stationed throughout the country. They were joined in 1946 by another 40,000-plus troops from the British Commonwealth Forces—Britons, Australians, Indians, and New Zealanders.

The numbers of Allied soldiers in Japan fell sharply over 1946 and 1947, as it became clear that the Occupation would be largely unopposed, and peaceful. Still, during its seven years there were never fewer than 100,000 military personnel—mostly men between the ages of 18 and 24—garrisoned in dozens of bases scattered about the four main islands of Japan. During the Korean War (1951-1953), American troop strength in Japan actually rose again, reaching the figure of 260,000 GIs by 1952.[1] Nor did those soldiers necessarily go home when Japan regained its sovereignty in that year. The negotiations that ended the Occupation included a bilateral security treaty between Japan and the U.S. that provided for the indefinite continued existence of U.S. military bases. Today, there are still some 85 U.S. military installations in Japan. Most are in Okinawa, the group of islands that the U.S. military controlled until their reversion to Japan in 1972, but there continue to exist on the main islands a number of important bases belonging to the U.S. Marine Corps (Iwakuni, Camp Fuji), Air Force (Yokota, Misawa), Navy (Sasebo, Yokosuka, Atsugi), and Army (Zama).[2]

The constant cycling of hundreds of thousands of mostly American soldiers in and out of Japan had enormous effects on both countries, and on the world, that are still reverberating to this day. While scholars have studied many aspects of the Occupation, until recently the tendency has been to focus primarily on the one-way and top-down story of how Allied (primarily U.S.) policies and interests affected Japan, and especially Japanese elites: politicians, policymakers, business leaders, and intellectuals. Newer research has explored the active role of Japanese themselves in shaping the Occupation, and also some of the more quotidian aspects of the Occupation experience for ordinary as well as elite Japanese. A result of the latter project, in particular, has been fresh recognition of the impact of Allied soldiers and their bases on everyday life in Japan. What still tends to be overlooked, however, is the equally profound impact of Japan on its occupiers. The youthful Americans, Australians, and other Allied soldiers who completed tours of duty in Japan were also shaped by their experiences, which they took home with them when they departed—or on to other stops in their military careers.

One readily accessible body of materials directly pertaining to the experience of American GIs, especially, is to be found in American popular culture. This essay examines a single example: a collection of cartoons drawn and written by a Navy serviceman in the final two years of the Occupation, and republished in Japan and the U.S. in 1953 as a book titled Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation.[3] In the following sections I offer some suggestions as to how Babysan might be read as a means of gaining insight into the Occupation for the occupiers as well as the occupied, in Japan, the U.S., and beyond.

I. What Babysan Tells Us

Bill Hume (1916-2009), the main author of Babysan, was a naval reservist from Missouri who was called up in 1951 to serve in Japan at Atsugi naval air base. A commercial artist in civilian life, Hume began publishing cartoons about American soldiers in various military periodicals, such as the Pacific editions of the Stars and Stripes and Navy Times. His best-known cartoons concerned the erotic interactions of Navy servicemen with young Japanese women or, as he dubbed them, “Babysan.” Hume and his co-author, a Navy journalist named John Annarino (1930-2009), explain in Babysan that the name is an American-Japanese blend:

San may be assumed to mean mister, missus, master or miss. Babysan, then, can be translated literally to mean “Miss Baby.” The American, seeing a strange girl on the street, can’t just yell, “hey, baby!” He is in Japan, where politeness is a necessity and not a luxury, so he deftly adds the title of respect. It speeds up introductions. [Babysan, 16]

Most directly, Babysan offers us insights into the critical question of how American soldiers actually behaved toward Japanese civilians: What was the nature of relations between occupiers and occupied? In addition to explaining the origins of the term “Babysan,” for example, the quotation above paints a vivid picture of what must have been a common scene on Occupation-era streets. Nor did Allied soldiers merely shout greetings at Japanese women. In recent years, a number of studies have explored the ubiquity during the occupation of Japan, as in the occupations of other countries after World War II, of sexual relations between occupying troops and civilian natives—or what the military called, disapprovingly, “fraternization.” As many as 70,000 women worked as prostitutes in brothels and other facilities that were established by the Japanese government to entertain (and pacify) Allied soldiers during the early years of the Occupation. And tens of thousands of other Japanese exchanged sexual favors for money or goods on a more casual, private basis in and around military installations. Yet the type of woman depicted in Babysan was not exactly an ordinary sex worker—or panpan, as they were often called—who made a living from short-term sexual encounters with servicemen. Hume focused, rather, on the greyer category of what were sometimes referred to as onrii (from “only” or “only one”), or women who engaged in serial, ostensibly monogamous relationships with “only one” uniformed lover at a time, and who received various forms of material compensation in return.[4]

As a document produced by and for American servicemen, Babysan may reveal more about them than it does about the women it purports to describe—but there are genuine if sometimes oblique insights here into the latter and their world. For example, much of the humor in Babysan derives from the tension between the American sailor’s good-willed, often naïve expectations of his new girlfriend (fidelity, romantic attachment, regular sexual availability) and the Japanese woman’s pragmatic and even deceitful determination to extract as much from him (and other Americans) as possible. Several cartoons note that she claims she has a family to support, and that her lover’s gifts are necessary for their survival, as well as her own. [figure 1]

Fig. 1

Her past possibly is not much different from that of many other girls. Her father was killed in the war, and although she was just a young girl she had to work to help her family. . . . Her aged mother is bent from toil in rice paddies; her brother wants to be a baseball player when he grows up, but of course he is a sickly child. The tales Babysan tells about members of her family are sometimes hard to believe. It seems uncanny that their body temperatures should rise and fall with Babysan’s financial status. [Babysan, 96]

The writer expresses skepticism, but many young women in Japan, as in war-devastated countries around the world, did indeed find themselves in such straits, and the access some were able to gain to the goods and cash brought by Allied personnel helped to support extended networks of family and others during a time of great material scarcity.

Also credible are the glimpses Babysan reveals of the hybrid mixtures of American and Japanese culture that sprang up almost immediately in the spaces of contact between servicemen and native women. The very term Babysan, along with many other examples of “Panglish” that appear in the cartoons (and in a mock-helpful glossary at the end of Babysan), attest to the linguistic creativity unleashed by military occupation. As suggested by several cartoons, as well as the book’s glossary, the ability of Japanese women to communicate in English was facilitated by the way in which certain Japanese terms and phrases became familiar to servicemen [Babysan, 89, 124-127]. The resulting pidgin was not an equal mix—inevitably the power imbalance favored English—but the phenomenon hints at the possibility that the impact of the Occupation included some degree of Japanization, and not simply one-way Americanization or Westernization. [figure 2]

Fig. 2

Similarly, there are several references to another hybrid cultural form that flourished in the zone of contact between occupiers and occupied: popular music. One cartoon depicts Babysan as she “jives and jitterbugs her way across the clubroom floor” with a sailor. [figure 3]

Fig. 3

The accompanying text identifies the tune as “Japanese Rhumba” [Babysan, 10-11]. “Japanese Rumba,” released in 1951 on the Japanese label Nippon Columbia, was just one of numerous hits—such as “Tokyo Boogie Woogie” (1949) or “Gomen-nasai (Forgive Me)” (1953)—that were produced in occupied (or recently occupied) Japan, and circulated there and beyond, in other parts of the world.[5]

II. What Babysan Doesn’t Tell Us

The question of what is missing from a document or source can be just as productive to ask as the question of what it contains. In Babysan there are a number of telling absences or ellipses. Perhaps most glaringly, the social world of Babysan is radically simplified and homogenous, suppressing much of the diversity that actually existed both on and off the military base. Social difference in Hume’s telling centers on the opposition between young Japanese women and their American boyfriends. That difference is gendered, and cultural, and it is also clearly racial, as underscored by the several cartoons that turn on the question of skin color. “No—not sunburn—just naturally brown!” is the caption to one, in which Babysan blithely opens her blouse for an ogling sailor [Babysan, 84-85; see also 37].[6] [figure 4]

Fig. 4

Yet Babysan’s focus on the fascination of white soldiers with the “colorful” bodies of Japanese women obscures the fact that not all Allied troops were white. A significant minority of African-Americans served in the Occupation, where they were segregated in all-black units until as late as 1951, and endured discriminatory policies and treatment on duty as well as off. Also important in occupied Japan were Asian-American and especially Japanese-American personnel, both male and female. Similarly, among the British Commonwealth troops who occupied Japan were Indian, Nepalese, and Maori units. Although there is ample evidence of social interaction, including sexual relations, between Japanese and non-white soldiers, Babysan’s occupiers are exclusively white men.[7] To include representations of non-white sailors was perhaps to introduce divisive questions of internal difference and inequality that would have mitigated against the humorous, “morale-building” function of military entertainment such as Hume’s cartoons. [figure 5]

Fig. 5. 1957 photograph by Tokiwa Toyoko of African-American servicemen and a Japanese woman, in Yokohama [8]

It may have been a similar logic that dictated the omission of any reference to Japanese society beyond the young women who “butterflyed” about military installations. Representations of anyone else might have reminded the viewer of other segments of the native population who were less complaisant, or who even resented the presence of Allied troops. [figure 6]

Fig. 6. Image taken from John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, 135. In this early postwar cartoon by Endô Takeo, the disabled Japanese veteran contemplates his former enemy, an American soldier who is enjoying the spoils of victory in occupied Japan.

During the Occupation and after, military bases, the neighborhoods of bars and brothels that grew up around them, and the denizens of both were regarded with suspicion, distaste, and anger by much of Japanese society. In addition to representing all the ignominy of foreign military occupation, to many Japanese the bases seemed almost inevitably to pollute the areas around them with a noxious mixture of alcohol and drugs, prostitution, violence, gambling, and black-marketeering. Indeed, since the 1950s there has been ongoing social activism by Japanese groups who protest U.S. military bases, and the various ways in which they can be said to harm surrounding communities.

Another important omission from Babysan is the much broader spectrum of interactions that occupying troops actually had with local women. It is not surprising that Hume would choose to overlook the ubiquity of ordinary prostitution, for example, or the regular occurrence of rape and other forms of sexual violence.[9] Neither was consonant with either the public image or the self-image of the U.S. military. What may be a little more difficult to understand, however, is Babysan’s silence on the possibility of lasting relationships leading to marriage. Instead, the basic assumption running throughout the collection is that: “All good things must come to an end. The boyfriend’s association with Babysan is no exception” [Babysan, 120]. In fact, however, many of the “associations” between Japanese women and their soldier boyfriends did not end; beginning as early as 1947, ever-increasing numbers of couples chose to marry. By the end of 1952, according to one source, over 10,000 Americans had married Japanese women. That number would only grow over the decade. Estimates of the numbers of Japanese “war brides” who migrated to the U.S. with American fiancés or husbands during the 1950s and 1960s have ranged as high as 50,000. To this must be added the figures for those who married Allied soldiers but stayed in Japan, and also those who migrated to other countries, such as England and Australia.[10]

In ignoring the very real and growing phenomenon of marriage between U.S. servicemen and Japanese women, Babysan points instead to the deep discomfort that surrounded the topic in the early 1950s. As noted above, the official military policy in Japan was to discourage “fraternization,” although in practice it tended to be tolerated as a necessary evil. Until U.S. immigration law was changed in 1952, however, marriage between Americans and Japanese nationals was explicitly and formally banned, on the grounds that Japanese were legally unable to enter the U.S. According to the so-called Oriental Exclusion Act (1924), Japanese (along with Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, and other “Orientals”) could not be admitted to the U.S. because their race made them ineligible for citizenship. And even after the passage of the McCarran Walter Act of 1952, which created limited opportunities for Asian immigration, “anti-miscegenation” laws criminalizing marriage (and sometimes even sexual relations) between members of different races remained in force until the 1960s in many individual American states. Hume’s insistence on the impermanent nature of relationships between American sailors and their Japanese girlfriends reflected not reality, therefore, but the desired effect of federal, state, and military laws, and the tense race relations that underpinned them.[11]

III. Babysan Travels

Babysan also serves as indirect evidence of the profound and enduring impact of the Occupation outside Japan. The tens of thousands of Japanese war brides who migrated to the U.S. and other Allied countries during the late 1940s and 1950s, for example, represented an important demographic event in the U.S. and elsewhere. Indeed, during the approximately forty years between the Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 and the 1965 Immigration Act, when the migration of Asians to the U.S. was radically curtailed, Japanese (and Korean) war brides were practically the only Asians to enter the country in significant numbers. Furthermore, the fact that the majority of these Asian migrants were married to white men (although sizable minorities married Asian-Americans and African-Americans), and became mothers to mixed-race American children, represented a notable challenge to the segregationist Jim Crow laws and ideology of 1950s America. The process by which mainstream American society came to accept Japanese and other Asian war brides might be said to have begun with cartoons like Babysan, and continued with other artifacts of American popular culture, such as popular songs, best-selling novels, and big-budget Hollywood films.[12] As one scholar has suggested, the extensive and increasingly positive coverage in the U.S. mass media of Japanese war brides and their “mixed” marriages with white men served in part to stand in for, and also occlude, larger and more intractable problems of black-white race relations in the dawning Civil Rights era.[13] [figure 7]

Fig. 7. Poster for Sayonara (dir. Joshua Logan, 1957)

As noted above, Babysan also suggests the possibility of an unintended Japanization of Americans that accompanied the effort to Americanize Japanese. In another volume of cartoons also published by Hume in 1953, titled When We Get Back Home from Japan, the repeated joke is that sailors shipped back “stateside” have retained some of the customs and tastes they picked up in Japan. American women look on in bemusement as their husbands sit on the floor, pick up telephones uttering the phrase “moshi moshi,” and try to open doors as if they were sliding shoji [When We Get Back Home from Japan, 5, 113, 24-25]. It is true, however, that the 1950s witnessed the rising popularity in the U.S. of Japan-themed culture—ranging from films, books, cuisine, and fashion to architecture and home design. The reasons for the growing 1950s American interest in Japanese art and design, including elements of interior décor such as shoji, are complex, but the Occupation experience was surely one important factor.[14] [figure 8]

Fig. 8

Finally, there is another sense in which Babysan might be said to “travel”--and also to persist. Hume’s cartoons are a vivid record of many of the habits and customs, attitudes, and images that were generated at the intersection of a war-torn East Asian society and expansive U.S. military installations. While the Occupation of Japan ended formally in 1952, hundreds of thousands of young American soldiers continued to cycle in and out of large, permanent U.S. military bases in Japan through the 1950s and beyond. U.S. bases in Japan were intimately connected, moreover, to American military involvement in other parts of Asia. In the Korean War, for example, U.S. bases in Japan served as the main staging area and sanctuary for American forces fighting on the peninsula. A decade later, the U.S. fought the Vietnam War from bases and installations in the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Guam, Okinawa, and also, again, Japan.[15] To give just one example of the way Babysan “traveled,” the very term “babysan,” like many other words, phrases, and images that first gained currency in occupied Japan, continued to be in use by American troops during the Vietnam War. According to one dictionary of Vietnam war slang, “babysan” was “used frequently in Vietnam,” where it referred to “an East Asian child; a young woman.”[16] Thus elements of “Babysan” culture have lived on and circulated within the massive U.S. Pacific Command--the sprawling complex of hundreds of military installations in the Pacific region that project American power in Asia and, more recently, toward the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. Many of those installations, especially in Okinawa and South Korea, are even today surrounded by bar neighborhoods centered on the sexual labor of young Asian women.[17]

In conclusion, this essay has sought to suggest just a few of the ways in which it is possible to read a single documentary source for insights into the Allied Occupation of Japan—and into the postwar history of Japan, the U.S., and East Asia. By considering one cartoonist’s humorous representations of interactions between American soldiers and Japanese women, we can deepen our understanding of a crucial event in twentieth-century world history, and its ongoing relevance for the present.

[1] I take these numbers on occupying troops in Japan from Eiji Takamae, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 53-55, 125-135.

[2] Information on the U.S. military presence in present-day Japan can be found on the official website of USFJ (U.S. Forces, Japan): http://www.usfj.mil.

[3] Bill Hume, with John Annarino, Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation (Tokyo: Kasuga Boeki K.K., 1953).

[4] On prostitution as well as onrii, see: John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1999), Chapter 4; Takemae, 68-71; Sarah Kovner, Occupying Power: Sex Workers and Servicemen in Postwar Japan (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2012).

[5] On popular music in Japan during the Occupation years, see Michael K. Bourdaghs, Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), Chapter 1. Many of the original recordings, as well as later versions, can be found on Youtube. See, for example, Harry Belafonte’s several recordings of his hit “Gomen-nasai.”

[6] According to the racial classifications that prevailed in 1950s America and elsewhere, the skin color of Japanese and other Asians was yellow. While Babysan emphasizes the idea that Japanese women are “colored,” Hume avoids describing Japanese skin color as yellow, and refers instead to its “brownness.”

[7] On ethnic (and gender) diversity among Allied troops in occupied Japan, see Takemae, 126-137.

[8] Tokiwa Toyoko, Kiken na adabana (Tokyo: Mikasa shobô, 1957), 43.

[9] On sexual violence perpetrated by Allied troops in Japan, see Takemae, 67; Kovner, 49-56.

[10] The figure of 10,517 marriages by 1953 is cited in Anselm L. Strauss, “Strain and Harmony in American-Japanese War-Bride Marriages,” Marriage and Family Living 16:2 (May 1954), 99-106. On the numbers of Japanese women who migrated to the U.S. as war brides, see: Bok-Lim C. Kim, “Asian Wives of U.S. Servicemen: Women in Shadows,” Amerasia 4:1 (1977) 91-115; Rogelio Saenz, Sean-Shong Hwang, Benigno E. Aguirre, “In Search of Asian War Brides,” Demography 31:3 (August 1994), 549-559.

[11] On the ban on marriages between Americans and Japanese, see Yukiko Koshiro, Trans-Pacific Racisms and the U.S. Occupation of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 156-200. See also: Susan Zeiger, Entangling Alliances: Foreign War Brides and American Soldiers in the Twentieth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 181-189.

[12] See, for example, the 1957 Hollywood film Sayonara, starring Marlon Brando as the American military officer who marries his true love, a Japanese woman.

[13] Caroline Chung Simpson, An Absent Presence: Japanese Americans in Postwar American Culture, 1945-1960 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), Chapter 5.

[14] For further discussion of the “Japan Boom” in 1950s America, see Brandt, Japan’s Cultural Miracle: Rethinking the Rise of a World Power, 1945-1965 (forthcoming, Columbia University Press).

[15] For a discussion of Japan’s involvement in the Vietnam War, see Thomas R. H. Havens, Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

[16] Tom Dalzell, Vietnam War Slang: A Dictionary on Historical Principles, (New York: Routledge, 2014), 5

[17] A good introduction to this topic is provided in Saundra Pollock Sturdevant and Brenda Stoltzfus, Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia (New York: The New Press, 1992).

Learning from Babysan

The Japanese government formally agreed to surrender to the Allied nations of World War II on August 14, 1945. Famously, at noon on the following day Emperor Hirohito’s taped announcement of surrender was broadcast to the nation by radio. Less than two weeks later, the first United States troops started to land at airfields and ports on the main island of Honshu, to begin the Allied Occupation of Japan (1945-1952). By the end of 1945, nearly half a million American soldiers were stationed throughout the country. They were joined in 1946 by another 40,000-plus troops from the British Commonwealth Forces—Britons, Australians, Indians, and New Zealanders.

The numbers of Allied soldiers in Japan fell sharply over 1946 and 1947, as it became clear that the Occupation would be largely unopposed, and peaceful. Still, during its seven years there were never fewer than 100,000 military personnel—mostly men between the ages of 18 and 24—garrisoned in dozens of bases scattered about the four main islands of Japan. During the Korean War (1951-1953), American troop strength in Japan actually rose again, reaching the figure of 260,000 GIs by 1952.[1] Nor did those soldiers necessarily go home when Japan regained its sovereignty in that year. The negotiations that ended the Occupation included a bilateral security treaty between Japan and the U.S. that provided for the indefinite continued existence of U.S. military bases. Today, there are still some 85 U.S. military installations in Japan. Most are in Okinawa, the group of islands that the U.S. military controlled until their reversion to Japan in 1972, but there continue to exist on the main islands a number of important bases belonging to the U.S. Marine Corps (Iwakuni, Camp Fuji), Air Force (Yokota, Misawa), Navy (Sasebo, Yokosuka, Atsugi), and Army (Zama).[2]

The constant cycling of hundreds of thousands of mostly American soldiers in and out of Japan had enormous effects on both countries, and on the world, that are still reverberating to this day. While scholars have studied many aspects of the Occupation, until recently the tendency has been to focus primarily on the one-way and top-down story of how Allied (primarily U.S.) policies and interests affected Japan, and especially Japanese elites: politicians, policymakers, business leaders, and intellectuals. Newer research has explored the active role of Japanese themselves in shaping the Occupation, and also some of the more quotidian aspects of the Occupation experience for ordinary as well as elite Japanese. A result of the latter project, in particular, has been fresh recognition of the impact of Allied soldiers and their bases on everyday life in Japan. What still tends to be overlooked, however, is the equally profound impact of Japan on its occupiers. The youthful Americans, Australians, and other Allied soldiers who completed tours of duty in Japan were also shaped by their experiences, which they took home with them when they departed—or on to other stops in their military careers.

One readily accessible body of materials directly pertaining to the experience of American GIs, especially, is to be found in American popular culture. This essay examines a single example: a collection of cartoons drawn and written by a Navy serviceman in the final two years of the Occupation, and republished in Japan and the U.S. in 1953 as a book titled Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation.[3] In the following sections I offer some suggestions as to how Babysan might be read as a means of gaining insight into the Occupation for the occupiers as well as the occupied, in Japan, the U.S., and beyond.

I. What Babysan Tells Us

Bill Hume (1916-2009), the main author of Babysan, was a naval reservist from Missouri who was called up in 1951 to serve in Japan at Atsugi naval air base. A commercial artist in civilian life, Hume began publishing cartoons about American soldiers in various military periodicals, such as the Pacific editions of the Stars and Stripes and Navy Times. His best-known cartoons concerned the erotic interactions of Navy servicemen with young Japanese women or, as he dubbed them, “Babysan.” Hume and his co-author, a Navy journalist named John Annarino (1930-2009), explain in Babysan that the name is an American-Japanese blend:

San may be assumed to mean mister, missus, master or miss. Babysan, then, can be translated literally to mean “Miss Baby.” The American, seeing a strange girl on the street, can’t just yell, “hey, baby!” He is in Japan, where politeness is a necessity and not a luxury, so he deftly adds the title of respect. It speeds up introductions. [Babysan, 16]

Most directly, Babysan offers us insights into the critical question of how American soldiers actually behaved toward Japanese civilians: What was the nature of relations between occupiers and occupied? In addition to explaining the origins of the term “Babysan,” for example, the quotation above paints a vivid picture of what must have been a common scene on Occupation-era streets. Nor did Allied soldiers merely shout greetings at Japanese women. In recent years, a number of studies have explored the ubiquity during the occupation of Japan, as in the occupations of other countries after World War II, of sexual relations between occupying troops and civilian natives—or what the military called, disapprovingly, “fraternization.” As many as 70,000 women worked as prostitutes in brothels and other facilities that were established by the Japanese government to entertain (and pacify) Allied soldiers during the early years of the Occupation. And tens of thousands of other Japanese exchanged sexual favors for money or goods on a more casual, private basis in and around military installations. Yet the type of woman depicted in Babysan was not exactly an ordinary sex worker—or panpan, as they were often called—who made a living from short-term sexual encounters with servicemen. Hume focused, rather, on the greyer category of what were sometimes referred to as onrii (from “only” or “only one”), or women who engaged in serial, ostensibly monogamous relationships with “only one” uniformed lover at a time, and who received various forms of material compensation in return.[4]

As a document produced by and for American servicemen, Babysan may reveal more about them than it does about the women it purports to describe—but there are genuine if sometimes oblique insights here into the latter and their world. For example, much of the humor in Babysan derives from the tension between the American sailor’s good-willed, often naïve expectations of his new girlfriend (fidelity, romantic attachment, regular sexual availability) and the Japanese woman’s pragmatic and even deceitful determination to extract as much from him (and other Americans) as possible. Several cartoons note that she claims she has a family to support, and that her lover’s gifts are necessary for their survival, as well as her own. [figure 1]

Fig. 1

Her past possibly is not much different from that of many other girls. Her father was killed in the war, and although she was just a young girl she had to work to help her family. . . . Her aged mother is bent from toil in rice paddies; her brother wants to be a baseball player when he grows up, but of course he is a sickly child. The tales Babysan tells about members of her family are sometimes hard to believe. It seems uncanny that their body temperatures should rise and fall with Babysan’s financial status. [Babysan, 96]

The writer expresses skepticism, but many young women in Japan, as in war-devastated countries around the world, did indeed find themselves in such straits, and the access some were able to gain to the goods and cash brought by Allied personnel helped to support extended networks of family and others during a time of great material scarcity.

Also credible are the glimpses Babysan reveals of the hybrid mixtures of American and Japanese culture that sprang up almost immediately in the spaces of contact between servicemen and native women. The very term Babysan, along with many other examples of “Panglish” that appear in the cartoons (and in a mock-helpful glossary at the end of Babysan), attest to the linguistic creativity unleashed by military occupation. As suggested by several cartoons, as well as the book’s glossary, the ability of Japanese women to communicate in English was facilitated by the way in which certain Japanese terms and phrases became familiar to servicemen [Babysan, 89, 124-127]. The resulting pidgin was not an equal mix—inevitably the power imbalance favored English—but the phenomenon hints at the possibility that the impact of the Occupation included some degree of Japanization, and not simply one-way Americanization or Westernization. [figure 2]

Fig. 2

Similarly, there are several references to another hybrid cultural form that flourished in the zone of contact between occupiers and occupied: popular music. One cartoon depicts Babysan as she “jives and jitterbugs her way across the clubroom floor” with a sailor. [figure 3]

Fig. 3

The accompanying text identifies the tune as “Japanese Rhumba” [Babysan, 10-11]. “Japanese Rumba,” released in 1951 on the Japanese label Nippon Columbia, was just one of numerous hits—such as “Tokyo Boogie Woogie” (1949) or “Gomen-nasai (Forgive Me)” (1953)—that were produced in occupied (or recently occupied) Japan, and circulated there and beyond, in other parts of the world.[5]

II. What Babysan Doesn’t Tell Us

The question of what is missing from a document or source can be just as productive to ask as the question of what it contains. In Babysan there are a number of telling absences or ellipses. Perhaps most glaringly, the social world of Babysan is radically simplified and homogenous, suppressing much of the diversity that actually existed both on and off the military base. Social difference in Hume’s telling centers on the opposition between young Japanese women and their American boyfriends. That difference is gendered, and cultural, and it is also clearly racial, as underscored by the several cartoons that turn on the question of skin color. “No—not sunburn—just naturally brown!” is the caption to one, in which Babysan blithely opens her blouse for an ogling sailor [Babysan, 84-85; see also 37].[6] [figure 4]

Fig. 4

Yet Babysan’s focus on the fascination of white soldiers with the “colorful” bodies of Japanese women obscures the fact that not all Allied troops were white. A significant minority of African-Americans served in the Occupation, where they were segregated in all-black units until as late as 1951, and endured discriminatory policies and treatment on duty as well as off. Also important in occupied Japan were Asian-American and especially Japanese-American personnel, both male and female. Similarly, among the British Commonwealth troops who occupied Japan were Indian, Nepalese, and Maori units. Although there is ample evidence of social interaction, including sexual relations, between Japanese and non-white soldiers, Babysan’s occupiers are exclusively white men.[7] To include representations of non-white sailors was perhaps to introduce divisive questions of internal difference and inequality that would have mitigated against the humorous, “morale-building” function of military entertainment such as Hume’s cartoons. [figure 5]

Fig. 5. 1957 photograph by Tokiwa Toyoko of African-American servicemen and a Japanese woman, in Yokohama [8]

It may have been a similar logic that dictated the omission of any reference to Japanese society beyond the young women who “butterflyed” about military installations. Representations of anyone else might have reminded the viewer of other segments of the native population who were less complaisant, or who even resented the presence of Allied troops. [figure 6]

Fig. 6. Image taken from John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II, 135. In this early postwar cartoon by Endô Takeo, the disabled Japanese veteran contemplates his former enemy, an American soldier who is enjoying the spoils of victory in occupied Japan.

During the Occupation and after, military bases, the neighborhoods of bars and brothels that grew up around them, and the denizens of both were regarded with suspicion, distaste, and anger by much of Japanese society. In addition to representing all the ignominy of foreign military occupation, to many Japanese the bases seemed almost inevitably to pollute the areas around them with a noxious mixture of alcohol and drugs, prostitution, violence, gambling, and black-marketeering. Indeed, since the 1950s there has been ongoing social activism by Japanese groups who protest U.S. military bases, and the various ways in which they can be said to harm surrounding communities.

Another important omission from Babysan is the much broader spectrum of interactions that occupying troops actually had with local women. It is not surprising that Hume would choose to overlook the ubiquity of ordinary prostitution, for example, or the regular occurrence of rape and other forms of sexual violence.[9] Neither was consonant with either the public image or the self-image of the U.S. military. What may be a little more difficult to understand, however, is Babysan’s silence on the possibility of lasting relationships leading to marriage. Instead, the basic assumption running throughout the collection is that: “All good things must come to an end. The boyfriend’s association with Babysan is no exception” [Babysan, 120]. In fact, however, many of the “associations” between Japanese women and their soldier boyfriends did not end; beginning as early as 1947, ever-increasing numbers of couples chose to marry. By the end of 1952, according to one source, over 10,000 Americans had married Japanese women. That number would only grow over the decade. Estimates of the numbers of Japanese “war brides” who migrated to the U.S. with American fiancés or husbands during the 1950s and 1960s have ranged as high as 50,000. To this must be added the figures for those who married Allied soldiers but stayed in Japan, and also those who migrated to other countries, such as England and Australia.[10]

In ignoring the very real and growing phenomenon of marriage between U.S. servicemen and Japanese women, Babysan points instead to the deep discomfort that surrounded the topic in the early 1950s. As noted above, the official military policy in Japan was to discourage “fraternization,” although in practice it tended to be tolerated as a necessary evil. Until U.S. immigration law was changed in 1952, however, marriage between Americans and Japanese nationals was explicitly and formally banned, on the grounds that Japanese were legally unable to enter the U.S. According to the so-called Oriental Exclusion Act (1924), Japanese (along with Chinese, Indians, Filipinos, and other “Orientals”) could not be admitted to the U.S. because their race made them ineligible for citizenship. And even after the passage of the McCarran Walter Act of 1952, which created limited opportunities for Asian immigration, “anti-miscegenation” laws criminalizing marriage (and sometimes even sexual relations) between members of different races remained in force until the 1960s in many individual American states. Hume’s insistence on the impermanent nature of relationships between American sailors and their Japanese girlfriends reflected not reality, therefore, but the desired effect of federal, state, and military laws, and the tense race relations that underpinned them.[11]

III. Babysan Travels

Babysan also serves as indirect evidence of the profound and enduring impact of the Occupation outside Japan. The tens of thousands of Japanese war brides who migrated to the U.S. and other Allied countries during the late 1940s and 1950s, for example, represented an important demographic event in the U.S. and elsewhere. Indeed, during the approximately forty years between the Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 and the 1965 Immigration Act, when the migration of Asians to the U.S. was radically curtailed, Japanese (and Korean) war brides were practically the only Asians to enter the country in significant numbers. Furthermore, the fact that the majority of these Asian migrants were married to white men (although sizable minorities married Asian-Americans and African-Americans), and became mothers to mixed-race American children, represented a notable challenge to the segregationist Jim Crow laws and ideology of 1950s America. The process by which mainstream American society came to accept Japanese and other Asian war brides might be said to have begun with cartoons like Babysan, and continued with other artifacts of American popular culture, such as popular songs, best-selling novels, and big-budget Hollywood films.[12] As one scholar has suggested, the extensive and increasingly positive coverage in the U.S. mass media of Japanese war brides and their “mixed” marriages with white men served in part to stand in for, and also occlude, larger and more intractable problems of black-white race relations in the dawning Civil Rights era.[13] [figure 7]

Fig. 7. Poster for Sayonara (dir. Joshua Logan, 1957)

As noted above, Babysan also suggests the possibility of an unintended Japanization of Americans that accompanied the effort to Americanize Japanese. In another volume of cartoons also published by Hume in 1953, titled When We Get Back Home from Japan, the repeated joke is that sailors shipped back “stateside” have retained some of the customs and tastes they picked up in Japan. American women look on in bemusement as their husbands sit on the floor, pick up telephones uttering the phrase “moshi moshi,” and try to open doors as if they were sliding shoji [When We Get Back Home from Japan, 5, 113, 24-25]. It is true, however, that the 1950s witnessed the rising popularity in the U.S. of Japan-themed culture—ranging from films, books, cuisine, and fashion to architecture and home design. The reasons for the growing 1950s American interest in Japanese art and design, including elements of interior décor such as shoji, are complex, but the Occupation experience was surely one important factor.[14] [figure 8]

Fig. 8

Finally, there is another sense in which Babysan might be said to “travel”--and also to persist. Hume’s cartoons are a vivid record of many of the habits and customs, attitudes, and images that were generated at the intersection of a war-torn East Asian society and expansive U.S. military installations. While the Occupation of Japan ended formally in 1952, hundreds of thousands of young American soldiers continued to cycle in and out of large, permanent U.S. military bases in Japan through the 1950s and beyond. U.S. bases in Japan were intimately connected, moreover, to American military involvement in other parts of Asia. In the Korean War, for example, U.S. bases in Japan served as the main staging area and sanctuary for American forces fighting on the peninsula. A decade later, the U.S. fought the Vietnam War from bases and installations in the Philippines, South Korea, Taiwan, Guam, Okinawa, and also, again, Japan.[15] To give just one example of the way Babysan “traveled,” the very term “babysan,” like many other words, phrases, and images that first gained currency in occupied Japan, continued to be in use by American troops during the Vietnam War. According to one dictionary of Vietnam war slang, “babysan” was “used frequently in Vietnam,” where it referred to “an East Asian child; a young woman.”[16] Thus elements of “Babysan” culture have lived on and circulated within the massive U.S. Pacific Command--the sprawling complex of hundreds of military installations in the Pacific region that project American power in Asia and, more recently, toward the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. Many of those installations, especially in Okinawa and South Korea, are even today surrounded by bar neighborhoods centered on the sexual labor of young Asian women.[17]

In conclusion, this essay has sought to suggest just a few of the ways in which it is possible to read a single documentary source for insights into the Allied Occupation of Japan—and into the postwar history of Japan, the U.S., and East Asia. By considering one cartoonist’s humorous representations of interactions between American soldiers and Japanese women, we can deepen our understanding of a crucial event in twentieth-century world history, and its ongoing relevance for the present.

[1] I take these numbers on occupying troops in Japan from Eiji Takamae, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 53-55, 125-135.

[2] Information on the U.S. military presence in present-day Japan can be found on the official website of USFJ (U.S. Forces, Japan): http://www.usfj.mil.

[3] Bill Hume, with John Annarino, Babysan: A Private Look at the Japanese Occupation (Tokyo: Kasuga Boeki K.K., 1953).

[4] On prostitution as well as onrii, see: John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1999), Chapter 4; Takemae, 68-71; Sarah Kovner, Occupying Power: Sex Workers and Servicemen in Postwar Japan (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2012).

[5] On popular music in Japan during the Occupation years, see Michael K. Bourdaghs, Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), Chapter 1. Many of the original recordings, as well as later versions, can be found on Youtube. See, for example, Harry Belafonte’s several recordings of his hit “Gomen-nasai.”

[6] According to the racial classifications that prevailed in 1950s America and elsewhere, the skin color of Japanese and other Asians was yellow. While Babysan emphasizes the idea that Japanese women are “colored,” Hume avoids describing Japanese skin color as yellow, and refers instead to its “brownness.”

[7] On ethnic (and gender) diversity among Allied troops in occupied Japan, see Takemae, 126-137.

[8] Tokiwa Toyoko, Kiken na adabana (Tokyo: Mikasa shobô, 1957), 43.

[9] On sexual violence perpetrated by Allied troops in Japan, see Takemae, 67; Kovner, 49-56.

[10] The figure of 10,517 marriages by 1953 is cited in Anselm L. Strauss, “Strain and Harmony in American-Japanese War-Bride Marriages,” Marriage and Family Living 16:2 (May 1954), 99-106. On the numbers of Japanese women who migrated to the U.S. as war brides, see: Bok-Lim C. Kim, “Asian Wives of U.S. Servicemen: Women in Shadows,” Amerasia 4:1 (1977) 91-115; Rogelio Saenz, Sean-Shong Hwang, Benigno E. Aguirre, “In Search of Asian War Brides,” Demography 31:3 (August 1994), 549-559.

[11] On the ban on marriages between Americans and Japanese, see Yukiko Koshiro, Trans-Pacific Racisms and the U.S. Occupation of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 156-200. See also: Susan Zeiger, Entangling Alliances: Foreign War Brides and American Soldiers in the Twentieth Century (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 181-189.

[12] See, for example, the 1957 Hollywood film Sayonara, starring Marlon Brando as the American military officer who marries his true love, a Japanese woman.

[13] Caroline Chung Simpson, An Absent Presence: Japanese Americans in Postwar American Culture, 1945-1960 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001), Chapter 5.

[14] For further discussion of the “Japan Boom” in 1950s America, see Brandt, Japan’s Cultural Miracle: Rethinking the Rise of a World Power, 1945-1965 (forthcoming, Columbia University Press).

[15] For a discussion of Japan’s involvement in the Vietnam War, see Thomas R. H. Havens, Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

[16] Tom Dalzell, Vietnam War Slang: A Dictionary on Historical Principles, (New York: Routledge, 2014), 5

[17] A good introduction to this topic is provided in Saundra Pollock Sturdevant and Brenda Stoltzfus, Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia (New York: The New Press, 1992).

向巴比桑學習

1945 年 8 月 14 日,日本政府正式同意向二戰同盟國投降。不到兩週後,第一批美國軍隊開始在本州島主島的機場和港口登陸,開始盟軍佔領日本(1945-1952)。到 1945 年底,近 50 萬美國士兵駐紮在全國各地。 1946 年,英聯邦軍隊的另外 4 萬多名士兵(英國人、澳洲人、印度人和紐西蘭人)加入了他們的行列。

1946 年和 1947 年期間,駐日盟軍士兵數量急劇下降,因為很明顯,佔領軍基本上不會遭到反對,而且是和平的。儘管如此,在成立的七年裡,散佈在日本四個主要島嶼上的數十個基地駐紮著不少於 10 萬名軍事人員(其中大多數是 18 歲至 24 歲的男性)。 在韓戰期間(1951-1953),美國在日本的駐軍人數實際上再次增加,到1952年達到26萬名美國士兵 。結束佔領的談判包括日本和美國之間的雙邊安全條約,該條約規定美國軍事基地無限期繼續存在。如今,美國在日本仍有約85處軍事設施。大多數位於沖繩島,沖繩島是美軍控制的島嶼群,直到 1972 年回歸日本為止,但主要島嶼上仍然存在一些屬於美國海軍陸戰隊的重要基地(岩國、富士營)、空軍基地陸軍(橫田、三澤)、海軍(佐世保、橫須賀、厚木)、陸軍(座間)。[2]

數十萬(主要是美國士兵)不斷地騎自行車進出日本,對兩國和世界產生了巨大影響,至今仍在產生影響。雖然學者們研究了佔領的許多方面,但直到最近,這種趨勢主要集中在盟軍(主要是美國)的政策和利益如何影響日本,特別是日本精英:政治家、政策制定者的單向和自上而下的故事上。較新的研究探討了日本人自身在塑造職業中的積極作用,以及普通和精英日本人職業經歷中的一些更常見的方面。特別是後一個計畫的結果是,人們重新認識到盟軍士兵及其基地對日本日常生活的影響。 然而,仍然容易被忽視的是日本對其佔領者同樣深遠的影響。在日本完成服役的年輕的美國、澳洲和其他盟軍士兵也受到了他們的經歷的影響,他們在離開日本或進入軍事生涯的其他站點時將這些經歷帶回家。

特別是在美國流行文化中可以找到與美國大兵的經驗直接相關的易於取得的資料。本文探討了一個例子:由一名海軍軍人在佔領時期最後兩年繪製和撰寫的漫畫集,並於 1953 年在日本和美國以書名《Babysan:私人審視日本佔領》一書的形式重新出版。[3] 在以下各節中,我將提供一些建議,說明如何解讀《巴比桑》,作為深入了解日本、美國及其他地區的佔領者和被佔領者的佔領的一種手段。

I. Babysan 告訴我們什麼

《Babysan》 的主要作者比爾·休謨(Bill Hume,1916-2009 年)是來自密蘇裡州的海軍預備役軍人,1951 年應徵入伍,在日本厚木海軍空軍基地服役。休謨是平民生活中的商業藝術家,他開始在各種軍事期刊上發表有關美國士兵的漫畫,例如太平洋版的《星條旗》和《海軍時報》。 他最著名的漫畫涉及海軍軍人與年輕的日本女性(他稱她們為“Babysan”)的色情互動。休謨和他的合著者、海軍記者約翰·安納裡諾(John Annarino,1930-2009 年)在《Babysan》中解釋說,這個名字是美國和日本的混合體:

San可以被認為是先生、夫人、主人或小姐的意思。那麼,Babysan 可以直譯為「寶貝小姐」。美國人在街上看到一個陌生的女孩,不能只是大喊:“嘿,寶貝!”他在日本,禮貌是必需品而不是奢侈品,因此他巧妙地加上了「尊重」這個稱呼。它加快了介紹速度。 [巴比桑,16]

最直接的是,巴比桑讓我們深入了解美國士兵實際上如何對待日本平民的關鍵問題:佔領者與被佔領者之間關係的本質是什麼?例如,除了解釋「Babysan」一詞的起源之外,上面的引文還生動地描繪了佔領時代街道上常見的場景。盟軍士兵也不僅僅只是向日本婦女大聲問候。近年來,許多研究探討了日本被佔領期間,就像二戰後其他國家被佔領期間一樣,佔領軍和平民之間普遍存在性關係——或者軍方不贊成地稱之為“兄弟化”。 。 在佔領初期,日本政府為娛樂(和安撫)盟軍士兵而設立的妓院和其他設施中,有多達 70,000 名婦女在那裡賣淫。數以萬計的其他日本人在軍事設施內及其周圍以更隨意、私密的方式用性恩惠換取金錢或物品。然而《巴比桑》中描繪的女性並不完全是一個普通的性工作者——或者人們常說的「盼盼」 ——她們靠與軍人的短期性接觸為生。相反,休謨關注的是有時被稱為“ onrii”(來自“唯一”或“只有一個”)的灰色類別,即一次與“只有一個”穿制服的情人建立連續的、表面上一夫一妻制關係的女性,並獲得各種形式的物質補償作為回報。[4]

作為一部由美國軍人製作並為美國軍人製作的文件,《巴比桑》可能比它所描述的女性更多地揭示了他們的情況——但這裡對後者及其世界有真實的、有時是間接的洞察。例如,《巴巴桑》中的大部分幽默都源於美國水手對新女友的善意但常常天真的期望(忠誠、浪漫的依戀、經常發生性行為)與日本女人務實甚至欺騙性的決心之間的緊張關係。幾部漫畫指出,她聲稱自己有一個家庭需要養活,而她愛人的禮物對於他們以及她自己的生存都是必要的。 [圖1]

圖1

她的過去可能與許多其他女孩沒有太大不同。她的父親在戰爭中喪生,儘管她只是一個小女孩,但她必須工作來養家糊口。 。 。 。 年邁的母親正彎著腰在稻田裡工作。她的哥哥長大後想成為棒球運動員,但他當然是個體弱多病的孩子。巴比桑講述的關於她家人的故事有時令人難以置信。他們的體溫隨著巴比桑的經濟狀況而升降,這似乎有些不可思議。 [巴比桑,96]

作者對此表示懷疑,但日本的許多年輕女性,就像世界各地遭受戰爭蹂躪的國家一樣,確實發現自己陷入了這樣的困境,而一些人能夠獲得盟軍人員帶來的貨物和現金,這有助於支持在物質極度匱乏的時期,擴大家庭和他人的網絡。

同樣可信的還有巴比桑所揭示的美國和日本文化的混合體,這種混合體幾乎立即出現在軍人和土著婦女之間的接觸空間中。 「巴比桑」一詞,以及漫畫中出現的許多其他「Panglish」例子(以及「巴比桑」末尾的一個模擬有用的術語表中),證明了軍事佔領所釋放的語言創造力。正如幾幅漫畫以及書中的術語表所表明的那樣,日本女性用英語交流的能力是透過軍人熟悉某些日語術語和短語的方式來提高的[ Babysan , 89, 124-127]。由此產生的洋涇浜語並不是一種平等的混合體——權力不平衡不可避免地有利於英語——但這一現象暗示了佔領的影響可能包括某種程度的日本化,而不僅僅是單向的美國化或西方化。 [圖2]

圖2

同樣,也有一些文獻提到了另一種在佔領者和被佔領者接觸區蓬勃發展的混合文化形式:流行音樂。一幅漫畫描繪了巴比桑與一名水手「在俱樂部地板上跳來跳去」的情景。 [圖3]

圖3

隨附的文字將曲調標識為“日本倫巴”[ Babysan,10-11]。日本唱片公司 Nippon Columbia 於 1951 年發行的“日本倫巴”只是眾多熱門歌曲之一,例如“Tokyo Boogie Woogie”(1949 年)或“Gomen-nasai(請原諒我)”(1953 年)。或最近被佔領)的日本,並在日本及其以外的世界其他地區流通。[5]

二. Babysan 沒有告訴我們什麼

詢問文件或來源中缺少什麼內容與詢問其包含什麼內容一樣富有成效。在巴比桑中,有許多明顯的缺席或省略。 也許最引人注目的是,巴巴桑的社交世界極其簡單化和同質化,抑制了軍事基地內外實際存在的大部分多樣性。休謨所述的社會差異集中在年輕的日本女性和她們的美國男友之間的對立。這種差異是性別和文化的差異,而且顯然也是種族的差異,正如幾部探討膚色問題的漫畫所強調的。 “不——不是曬傷——只是自然的棕色!”是其中一張圖片的說明文字,其中巴比桑愉快地為一位凝視的水手打開她的襯衫 [巴比桑,84-85;另見 37]。[6] [圖4]

圖4

然而,巴巴桑關注的是白人士兵對日本女性「色彩繽紛」的身體的迷戀,掩蓋了一個事實,即並非所有盟軍都是白人。相當多的非裔美國人在佔領軍中服役,直到 1951 年為止,他們都被隔離在全黑人單位中,並在工作期間和下班時間都遭受歧視性政策和待遇。在被佔領的日本也很重要的是亞裔美國人,尤其是日裔美國人,無論男女。同樣,佔領日本的英聯邦軍隊中有印度人、尼泊爾人和毛利人的部隊。儘管有充足的證據表明日本士兵和非白人士兵之間存在社會互動,包括性關係,但巴比桑的佔領者完全是白人。[7] 納入非白人水手的代表可能會引入內部差異和不平等的分裂問題,這些問題會削弱休謨漫畫等軍事娛樂的幽默和「鼓舞士氣」的功能。 [圖5]

圖 5. 1957 年 Tokiwa Toyoko 在橫濱拍攝的非裔美國軍人和一名日本婦女的照片[8]

或許正是出於類似的邏輯,除了那些對軍事設施「蝴蝶結」的年輕女性之外,省略了對日本社會的任何提及。其他任何人的代表可能會讓觀眾想起其他部分的原住民,他們不太順從,甚至憎恨盟軍的存在。 [圖6]

圖 6. 圖片取自約翰·W·道爾 (John W. Dower),《擁抱失敗:二戰後的日本》,135。位殘疾的日本退伍軍人凝視著他的前敵人,一名正在享受戰爭的美國士兵。

在佔領期間及之後,日本社會的大部分人都對軍事基地、周圍的酒吧和妓院以及兩者的居民抱持懷疑、厭惡和憤怒的態度。除了代表外國軍事佔領的所有恥辱之外,對許多日本人來說,這些基地似乎不可避免地會用酒精和毒品、賣淫、暴力、賭博和黑市活動等有害混合物污染他們周圍的地區。事實上,自 1950 年代以來,日本團體一直持續進行社會活動,抗議美國軍事基地,並以各種方式傷害週邊社區。巴比桑

的另一個重要遺漏是佔領軍實際上與當地婦女進行了更廣泛的互動。例如,休謨選擇忽視普遍存在的普通賣淫,或經常發生的強姦和其他形式的性暴力,這並不奇怪。[9] 兩者都不符合美國軍隊的公眾形像或自我形象。然而,可能有點難以理解的是,巴比桑對持久關係導致婚姻的可能性保持沉默。相反,貫穿整個系列的基本假設是:「所有美好的事情都必須結束。男友與 Babysan 的交往也不例外」[ Babysan,120]。然而事實上,日本女性和她們的軍人男友之間的許多「交往」並沒有結束。早在 1947 年開始,越來越多的夫婦選擇結婚。據一位消息人士稱,到 1952 年底,已有超過 10,000 名美國人與日本女性結婚。這個數字在十年內只會成長。據估計,在 1950 年代和 1960 年代,與美國未婚夫或丈夫一起移民到美國的日本「戰爭新娘」人數高達 50,000 人。除此之外,還必須加上與盟軍士兵結婚但留在日本的人數,以及移民到英國和澳洲等其他國家的人數。[10]

巴比桑 忽視了美國軍人和日本女性之間非常真實且日益增長的婚姻現象,相反,他指出了 20 世紀 50 年代初圍繞這一話題的深深的不適。 如上所述,日本的官方軍事政策是阻止“親善”,儘管實際上它往往被視為必要的罪惡而被容忍。然而,直到1952 年美國移民法修改之前,美國人與日本國民之間的婚姻都被明確、正式禁止,理由是日本人在法律上無法進入美國。 ,日本人(以及中國人、印度人、菲律賓人和其他「東方人」)無法進入美國,因為他們的種族使他們沒有資格獲得公民身份。 即使在1952 年《麥卡倫沃爾特法案》通過後,為亞洲移民創造了有限的機會,將不同種族成員之間的婚姻(有時甚至是性關係)定為犯罪的「反混血」法律仍然有效,直到20 世紀60 年代,許多個人美國各州。因此,休謨堅持認為美國水手和日本女友之間的關係是無常的,這反映的並不是現實,而是聯邦、州和軍事法律的預期效果,以及支撐這些法律的緊張種族關係。[11]

三.巴比桑遊記

巴比桑也間接證明了日本以外的佔領所產生的深遠而持久的影響。例如,在 1940 年代末和 1950 年代,數以萬計的日本戰爭新娘移民到美國和其他盟國,這代表了美國和其他地方的一個重要的人口事件。事實上,在1924 年《排華法案》和1965 年《移民法案》之間的大約四十年間,亞洲人向美國移民的數量大幅減少,日本(和韓國)戰爭新娘實際上是唯一進入美國的亞洲人。 此外,這些亞洲移民中的大多數與白人結婚(儘管相當多的少數人與亞裔美國人和非裔美國人結婚),並成為混血美國兒童的母親,這一事實對種族隔離法構成了顯著挑戰和 20 世紀 50 年代美國的意識形態。美國主流社會接受日本和其他亞洲戰爭新娘的過程可以說是從像《寶貝桑》這樣的動畫片開始的,並延續到美國流行文化的其他產物,如流行歌曲、暢銷小說和大片。 。[12] 正如一位學者所指出的,美國大眾媒體對日本戰爭新娘及其與白人的「混血」婚姻進行了廣泛且日益積極的報道,這在一定程度上代表並掩蓋了更大、更棘手的問題即將到來的民權時代的黑人與白人種族關係。[13] [圖7]

圖 7. 《再見》海報(導演:約書亞洛根,1957 年)

如上所述,巴比桑也表明,在日本人美國化的同時,美國人也可能出現無意的日本化。在休謨於 1953 年出版的另一本漫畫中,題為《當我們從日本回家時》中,反復出現的笑話是,被運回“美國本土”的水手們保留了他們在日本學到的一些習俗和品味。美國婦女困惑地看著她們的丈夫坐在地板上,拿起電話,說出“moshi moshi”,並試圖打開門,就像在滑動障子一樣[當我們從日本回家時,5, 113, 24 -25]。然而,20 世紀 50 年代確實見證了日本主題文化在美國日益流行——從電影、書籍、美食、時尚到建築和家居設計。 20 世紀 50 年代美國人對日本藝術和設計(包括障子等室內裝飾元素)興趣日益濃厚的原因很複雜,但職業經歷無疑是一個重要因素。[14] [圖8]

圖8

最後,還有另一個意義,可以說巴巴桑是「旅行」──也是堅持。休謨的漫畫生動地記錄了飽受戰爭蹂躪的東亞社會和廣闊的美國軍事設施交匯處所產生的許多習慣、習俗、態度和形象。雖然對日本的佔領於 1952 年正式結束,但在 20 世紀 50 年代及以後,數十萬年輕美國士兵繼續騎車進出美國在日本的大型永久軍事基地。 此外,美國在日本的基地與美國在亞洲其他地區的軍事介入密切相關。例如,在韓戰中,美國駐日本基地是美軍在半島作戰的主要集結地和庇護所。十年後,美國在菲律賓、韓國、台灣、關島、沖繩島以及日本的基地和設施進行了越戰。[15]舉一個巴比桑「旅行」方式的例子,「巴比桑」這個詞,就像許多其他在被佔領的日本首次流行的單字、短語和圖像一樣,在二戰期間繼續被美國軍隊使用。根據一本越南戰爭俚語詞典,“babysan”“在越南經常使用”,指的是“東亞孩子;一個年輕女子。[16] 因此,「巴比桑」文化的元素在龐大的美國太平洋司令部中得以延續和傳播——這是太平洋地區數百個軍事設施的龐大綜合體,這些設施將美國的力量投射到亞洲,最近投射到波斯灣和印度洋。其中許多設施,尤其是在沖繩和韓國,即使在今天,也被以亞洲年輕女性性勞動為中心的酒吧街區所包圍。[17]

總之,本文試圖提出幾種閱讀單一文獻資料的方法,以深入了解盟軍對日本的佔領以及日本、美國和東亞的戰後歷史。透過思考一位漫畫家對美國士兵和日本婦女之間互動的幽默描繪,我們可以加深對二十世紀世界歷史上的一個關鍵事件的理解,及其與當下的持續相關性。

[1]這些有關日本佔領軍的數字取自 Eiji Takamae, Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and its Legacy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 53-55, 125-135。

[2]有關美國在當今日本的軍事存在的資訊可以在 USFJ(美國軍隊,日本)的官方網站上找到:http://www.usfj.mil。

[3]比爾休謨 (Bill Hume) 與約翰安納裡諾 (John Annarino) 合著,《Babysan:私人審視日本佔領》(東京:Kasuga Boeki KK,1953 年)。

[4]關於賣淫與性行為,請參閱:John Dower,擁抱失敗:二戰後的日本(紐約:WW Norton and Co.,1999),第 4 章;武前,68-71;莎拉‧科夫納 (Sarah Kovner),《佔領權力:戰後日本的性工作者和軍人》(帕洛阿爾托:史丹佛大學出版社,2012 年)。

[5]關於佔領時期日本的流行音樂,請參閱 Michael K. Bourdaghs, Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), Chapter 1. 許多原創錄音以及更高版本可以在Youtube 上找到。例如,請參閱 Harry Belafonte 的幾張熱門歌曲“Gomen-nasai”的錄音。

[6]根據1950年代美國和其他地方盛行的種族分類,日本人和其他亞洲人的膚色是黃色的。雖然巴比桑強調日本女性是“有色人種”,但休謨避免將日本膚色描述為黃色,而是指其“棕色”。

[7]關於佔領日本的盟軍部隊的種族(和性別)多樣性,請參閱 Takemae,126-137。

[8] Tokiwa Toyoko,Kiken na adabana(東京:Mikasa shobô,1957),43。

[9]關於盟軍在日本實施的性暴力,請參閱 Takemae,67;科夫納,49-56。

[10] Anselm L. Strauss, “Strain and Harmony in American-Japan War-Bride Marriages,” Marriage and Family Living 16:2 (May 1954), 99-106引用了 1953 年 10,517 樁婚姻的數字。關於作為戰爭新娘移居美國的日本女性數量,請參閱:Bok-Lim C. Kim,“美國軍人的亞洲妻子:陰影中的女性”,Amerasia 4:1 (1977) 91-115; Rogelio Saenz、Sean-Shong Hwang、Benigno E. Aguirre,“尋找亞洲戰爭新娘”,人口統計31:3(1994 年 8 月),549-559。

[11]關於美國人與日本人之間的婚姻禁令,請參閱 Yukiko Koshiro,Trans-Pacific Racisms and the US Occupation of Japan (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 156-200。另請參閱:Susan Zeiger,《糾纏聯盟:二十世紀的外國戰爭新娘和美國士兵》(紐約:紐約大學出版社,2010 年),181-189。

[12]例如,1957 年的好萊塢電影《再見》由馬龍·白蘭度主演,飾演一位與真愛日本女子結婚的美國軍官。

[13]卡洛琳‧鐘‧辛普森(Caroline Chung Simpson),《缺席的存在:戰後美國文化中的日裔美國人,1945-1960》(達勒姆:杜克大學出版社,2001) ,第5章。

[14]有關 20 世紀 50 年代美國「日本繁榮」的進一步討論,請參閱 Brandt,《日本的文化奇蹟:重新思考世界強國的崛起,1945-1965 》 (即將出版,哥倫比亞大學出版社)。

[15]有關日本捲入越戰的討論,請參閱 Thomas RH Havens,《Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965-1975》(普林斯頓:普林斯頓大學出版社,1987 年)。

[16] Tom Dalzell,《越戰俚語:歷史原則字典》,(紐約:Routledge,2014 年),5

[17] Saundra Pollock Sturdevant 和 Brenda Stoltzfus 的《Let the Good Times Roll: Prostitution and the US Military in Asia》(紐約:The New Press,1992 年)對此主題進行了很好的介紹。

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。