歷史

沖繩雜誌,65年來促進友誼和理解,擴大視野

已發表

4年前在

2020 年 7 月 15 日

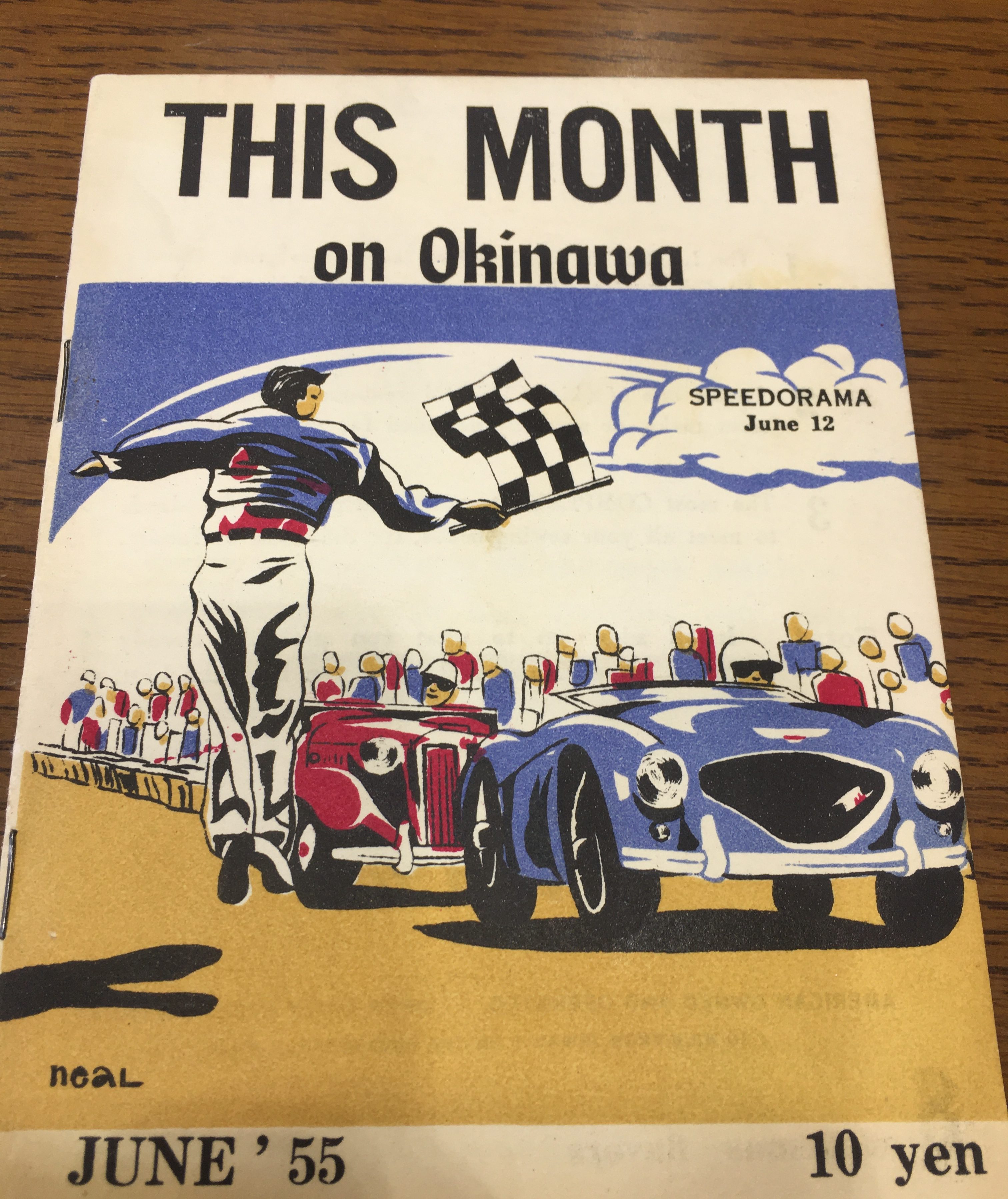

沖繩最古老的英文雜誌《This Week on Okinawa》於 6 月慶祝了創刊 65 週年。作為戰後日本最古老的英文出版物之一,它正在期待並計劃擴大其業務,以利用新技術和合作夥伴關係,同時回歸其根源。

該雜誌 長期以來一直是沖繩當地社區與島上美軍人員及其家人之間的文化和新聞橋樑,並且仍然是相互了解的重要管道。此外,它定期就基本問題和其他當地社會政治經濟問題提出建設性建議。

創辦雜誌

《沖繩週刊》於 1955 年 6 月創刊為月刊,1961 年 2 月開始改為週刊。該公司由已故的美國陸軍下士拉里·J·克雷布斯 (Larry J. Krebs) 創立,他於 1954 年在沖繩光榮退役並留了下來。

就讀於芝加哥大學(但未畢業)後,他被美國琉球群島民政管理局指派為名護市一所英語語言學校的校長(1950-1972 年)。目標是幫助學生為在美國學習的獎學金機會做好準備。

克雷布斯感嘆缺乏英語媒體來源(主要限於軍方的遠東網路廣播電台和太平洋 星條旗報),決定用 300 美元的遣散費創辦這本雜誌。

由於當時軍方領導的 USCAR 的反民主政策,他很難獲得出版許可。克雷布斯向軍事當局提出的第一次申請因缺乏資金而被拒絕。當他重新提出申請時,終於在 1954 年 12 月獲得許可,但期限只有三個月。

銀行不願意給他貸款,特別是如果未來軍方的許可不確定。同樣,投資者也不容易找到。此外,公司也不想在一本預期壽命也未知的未知雜誌上做廣告。

在接下來的六年裡,他不得不多次重新申請許可,先後獲得了六個月和兩年的許可,直到 1960 年他終於獲得了無限制的出版許可。

他第一次嘗試出版是1955 年春的《沖繩:沖繩和遠東季刊評論》。。那年 6 月,沖繩迎來了本月,需要更快的節奏和更快的生產週轉。五年半後,第一期周刊開始製作。

克雷布斯在當時浦添村牧港地區的塔特爾書店租了一間沒有電話的房間裡出版。他有一個以前的學生幫助他,但他最初必須包辦所有工作:所有者、編輯、記者、事實查核員、會計師、行銷人員、經銷商等。

最終,那位學生(宮原長信)成為了他的業務經理,並為克雷布斯提供了巨大的幫助。 「這對我們倆來說都是一個陡峭的學習曲線,」現年 92 歲的宮良最近在我在沖繩採訪他時告訴我。

印刷是由一家小型印刷店完成的,但排字工只能理解英語字母順序,克雷布斯還必須校對字體。因此,出版需要時間,而且很難準時完成。錢也很緊張。

在軍控沖繩開展活動

軍隊本身也讓事情變得困難。除了上述許可之外,他的報道偶爾也會引起不滿。

儘管克雷布斯曾在軍隊服役,但他並沒有從表面上接受軍隊的政策。事實上,他試圖解決美國沖繩政府的問題。

例如,他的一篇社論的標題是“GRI 的更多自治”,這是隸屬於 USCAR 管轄的琉球群島地方政府的縮寫。 20 世紀 50 年代被認為是政府的「黑暗歲月」。需要批評的聲音。

克雷布斯因其在沖繩的人文主義和自由主義而被媒體同事和他透過報道和生意結識的朋友所熟知。他的雜誌的座右銘是“激情、真理和準確性”。克雷布斯認真對待這些話,以及他向沖繩引入免費英語媒體的目標。

雜誌的第一期——一次性季刊——討論了它的信條。克雷布斯在題為「編輯台」的頁面上寫道,他認為「每本雜誌都應該有一個」。他的 300 字文章雖然沒有具體闡明該出版物的“指導原則或信念”,但討論了沖繩的戰略重要性,同時主張美國政府需要糾正政府方面的錯誤:

在無限的控制和幾乎無限的資金下,如果我們不能讓80萬琉球人實現美國夢,那麼8億亞洲人就會知道。我們不只會丟面子,還會丟臉。我們可能會失去亞洲。

克雷布斯後來將其描述為“當我們認為美國沖繩政策需要批評時,這是第一份批評美國沖繩政策的出版物。”此外,他指出 :

[感到]最自豪的是幫助將新聞自由的概念引入島上。沒有理由懷疑新聞自由在其他地方可能是好事,但在這裡卻不好——然而,長期以來,這就是島上負責人的觀點。沖繩自那時以來已經取得了長足的進步,並且還將走得更遠。這個月也會隨之而來。

由於這種批評,他不斷地與軍方領導層作鬥爭,而軍方領導層卻因不舒服而感到不舒服。 「有時,批評對像很難記住,」他在一期雜誌中寫道,「『國王陛下的忠誠反對派』這個概念是一個健康的概念。我們在這本雜誌中所說的話是以美國人、前軍人、新聞界代表和社區居民的身份說的。

在克雷布斯去世前不久出版的下一期中,他寫道:「高級專員[原文如此]是一項困難的工作,需要長期的學徒期。但明智的管理者知道何時讓步,何時在相對較小的問題上採取堅定立場。

已故的宮城悅二郎——在成為琉球大學新聞學教授和後來的沖繩縣檔案館第一任館長之前,曾是星條旗報記者——在他關於美國人和戰後沖繩的書中談到了克雷布斯的貢獻,以及一本關於沖繩報紙的書中。克雷布斯之所以受到“喜愛”,部分原因是他直接挑戰了沖繩的不公正現象。

宮原同意。克雷布斯“代表了沖繩人的感受和挫敗感。”這顯然讓他不受軍方歡迎,但他並不在意。

事實上,他對本月在沖繩「引入新聞自由的概念」 感到非常自豪:

新聞界以前可能是自由的,但沒有編輯敢於利用這種自由,有充分的理由知道這樣做是危險的。 56 年,任何敢於批評當地軍事或民事政府的出版物都會被關閉的感覺仍然很普遍。 「我們將繼續按照我們的看法做主,」我們那一年說。 “至於受到舊的舉手之勞,我們很久以前就認為世界上還有更糟糕的事情。”

克雷布斯在 1959 年的一次訪談中表示:「從某種意義上說,我的雜誌的獨立觀點已經過時了。琉球兩家日報(《琉球新報》和《沖繩泰穆蘇》)——其編輯喜歡說我的雜誌是島上第一本真正獨立的出版物——現在按他們所看到的方式印刷新聞。

今天的“本週”

克雷布斯的母親在他去世後接管了這家雜誌,並在生病前待了 10 年。隨後,她的員工購買了這家公司,其中一位名叫 ASHIMINE Kinsuke 的員工如今經營著這家公司,其員工數量比鼎盛時期要少得多。

由於技術進步、員工流動率低以及穩定的廣告收入,他有能力這樣做。自 20 世紀 70 年代初以來,它一直位於同一棟大樓內。

尤其重要的是,現在由沖繩人擁有並經營它。蘆峰本人出生於 1942 年 4 月 1 日,沖繩島戰役爆發三年後。他不僅經歷了與家人一起繞島逃亡的戰鬥,也經歷了戰後的各個階段。但他仍然保持著積極的態度,並為自己能夠將兩個社區團結在一起而感到自豪。

該雜誌贊助了當地學生的英語演講比賽,出版了一本有關沖繩的書,並介紹了無數跨越基地圍欄的友誼故事。

沖繩本週剛慶祝了成立 65 週年,目前正在考慮擴大其業務範圍,包括網路業務、視訊使用、舉辦講座以及與當地、國家和國際組織加強合作。這一點很重要,因為沖繩的英語讀者類型正在發生變化,而且市場已經擴展到沖繩以外的地區。

我們可以期待在 65 年後看到有人也撰寫有關這本重要周刊的 130 週年紀念的文章。

作者:羅伯特·D·埃爾德里奇博士

History

Untangling the Nanjing Incident and Its Many Historical Misrepresentations

Experts debate the validity of claims, misrepresentations, and authenticity of historical accounts at the heart of a new book on the Nanjing incident.

Published

8 hours agoon

September 25, 2024

A recent symposium focused on historian Bryan Mark Riggs' contentious book about the Nanjing Incident. Provocatively titled Japan's Holocaust, the volume was published in March. It has ignited discussions about historical representation and accuracy ever since.

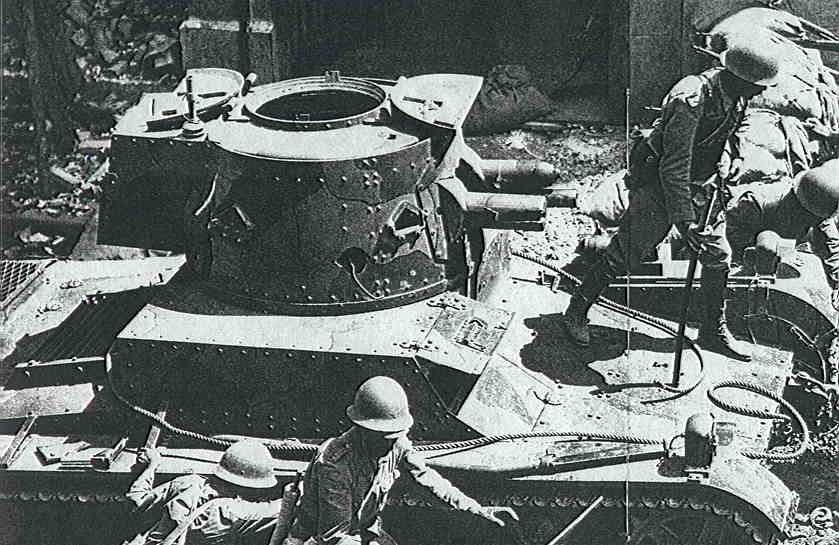

Three Japanese historians and experts scrutinized Riggs' claims, including his use of propaganda images. In doing so, they raised questions about their validity and context. Speakers discussed Riggs' reliance on American missionary accounts, which relied heavily on hearsay and often served as propaganda for the Chinese military. They also emphasized the need for careful historical analysis of Japan's actions during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

False Images

In his lecture, modern history researcher Ikuo Mizoguchi critically examined Riggs' use of Chinese propaganda photos, highlighting inaccuracies and misrepresentations. One photo Riggs used allegedly depicted Japanese soldiers rounding up villagers en masse appeared in the Memorial Hall of Victims in the Nanjing Massacre. Iris Chang also included it in her book, The Rape of Nanking. Chang claimed the image shows Japanese soldiers gathering thousands of women, many of whom were either gang-raped or forced into military prostitution. However, as Mizoguchi made clear, this photo dates to before that time and has no connection to Nanjing.

The image in question first appeared in the Asahi Graph, a weekly photo journal published in Japan, on November 10, 1937. This was approximately one month before the Battle of Nanjing. Taken in Paoshan, near Shanghai, the photograph actually shows Japanese soldiers protecting Chinese women and children returning from working in the fields.

Mizoguchi also dissected another photo. That one, Riggs claimed, showed the Japanese Army dragging the bodies of Nanking civilians into the Yangtze River. In reality, Japanese soldier Moriyasu Murase took this photo following a battle at Xinhe Town, near the river. Chinese forces, suffering heavy losses, attempted to retreat across the Yangtze on makeshift rafts. According to Mizoguchi, Japanese forces fired upon the retreating Chinese soldiers, resulting in further casualties.

Abusing the Term 'Holocaust'

In his book, Riggs argues that the so-called Nanking Massacre was representative of Japan's brutal behavior throughout the Second Sino-Japanese War. As part of this narrative, he emphasizes that widespread rape and murder also ensued after the Battle of Shanghai.

However, historian Kenichi Ara counters Riggs' argument based on extensive interviews with those who witnessed the fall of Nanking. These include key figures such as Hajime Onishi, former captain and staff officer of the Shanghai Expeditionary Forces, who later became the head of the Nanking Special Agency.

Ara scrutinizes Riggs' use of the term holocaust in his comparisons, questioning its appropriateness and contrasting it with Japan's documented efforts to protect Jewish refugees during World War II. Ara's analysis of the Battle of Shanghai offers a more nuanced view of Japan's actions, contradicting Riggs' depiction.

The Battle of Shanghai

The Battle of Shanghai began on August 13, 1937, during the Second Sino-Japanese War. As Japanese forces advanced, Hongkou residents fled across Suzhou Creek into the International Settlement and French Concession, seeking refuge.

By late August, the Imperial Japanese Army began landing in agricultural fields, far from urban areas, where numerous bunkers had been constructed. Local farmers had been displaced, so there were no civilian casualties initially. Ara explains. Fighting in South Shanghai continued for two weeks, concluding in early November.

Events in Suzhou

Following this, General Iwane Matsui ordered Onishi to protect the city of Suzhou, 100 kilometers northwest of Shanghai. Onishi arrived before the Japanese troops. "There, he posted signs forbidding the entry of Japanese troops, except for medical personnel," Ara states.

When the Japanese 35th Infantry Regiment finally entered Suzhou on November 19, they encountered minimal resistance, capturing roughly 2,000 Chinese soldiers. Journalists from the Asahi and Mainichi newspapers entered Suzhou, reporting on the situation as calm and orderly.

General Onishi visited the city's refugees and informed them the Japanese Army would not harm the city, encouraging them to return home. Subsequently, many residents began to make their way back into the city. Remarkably, despite the devastation, Suzhou's beauty remained intact, Ara says. Iconic landmarks like the North Temple Pagoda and its famous gardens were untouched by the conflict.

Japan's Jewish Refuge

Riggs employs the term Holocaust to describe the Imperial Japanese Army's actions. Contrary to this, however, the efforts of Japanese individuals to assist Jewish refugees reflect a humanitarian approach. This, Ara suggests, stands in stark contrast to the systematic atrocities associated with the Holocaust.

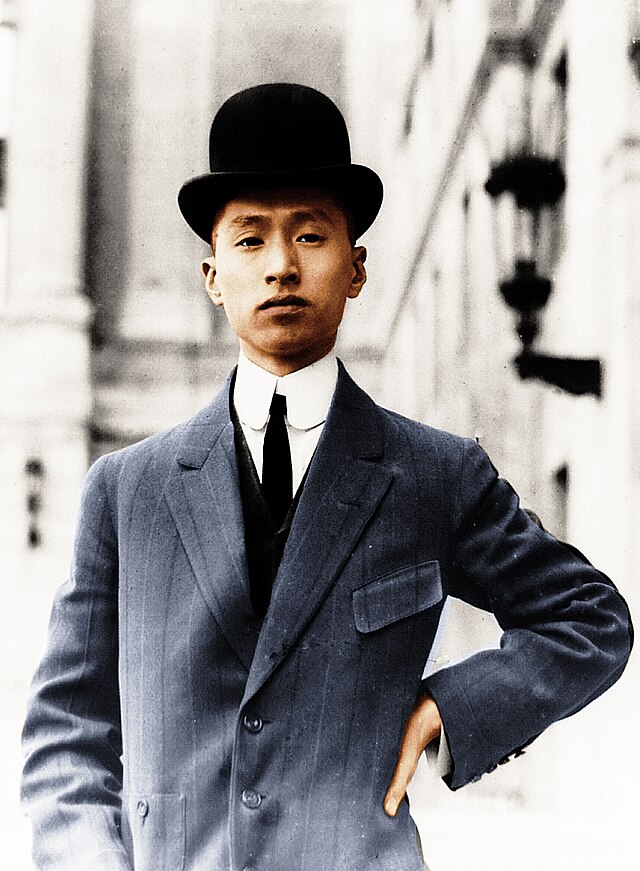

During the war, military figures like Kiichiro Higuchi, head of the Harbin Military Police, facilitated the entry of Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union into Manchukuo. In June 1940, Chiune Sugihara, acting as the Vice-Consul in Lithuania, issued visas to Jewish refugees escaping Poland.

As Ara points out, other notable individuals included Colonel Yasue Senko and Navy Captain Koreshige Inuzuka. Senko advocated for Jewish resettlement in Manchukuo, while Inuzuka played a crucial role in protecting Jewish refugees during their transit.

Members of the Pan-Asian Study Group had many debates about Japan's relationship with the Jews. The organization would eventually evolve into the Greater Asia Association, with General Iwane Matsui as its president. It aimed to establish partnerships with China while considering the prosperity of Asia as a whole. These four individuals who actively rescued Jews (Higuchi, Inuzuka, Matsui, and Sugihara) were all members of this association, with Higuchi and Inuzuka holding central positions.

Missionaries and Misinformation

Riggs also relied heavily on outdated evidence drawn from the accounts of US missionaries. History researcher Hisashi Ikeda questioned the authenticity of reports about Nanjing, particularly those based on hearsay from Western missionaries. He argued that "US missionaries, far from being neutral observers, actively supported Chiang Kai-shek's regime while seeking to promote Christianity." Moreover, they used the Nanjing Safety Zone to aid Chinese troops, forging the narrative of mass civilian killings.

The core allegations of the Nanjing Incident, particularly the claim that over 300,000 civilians were killed, emerged shortly after Japanese troops entered Nanjing on December 13, 1937. US missionaries, especially Miner Bates, played a pivotal role in spreading these claims. Bates, an advisor to the Chinese government, authored a memo that laid the foundation for many early reports.

The International Committee for the Nanjing Safety Zone, consisting of Western missionaries and observers, documented alleged atrocities. However, according to Ikeda, "many reports, including John Rabe's diary, were based on hearsay and lacked verification," casting doubt on their authenticity.

Even before the Japanese entered Nanjing, the Protestant Church in China had pledged its support to Chiang's New Life Movement. Missionaries, under the guise of protecting civilians, actively assisted the Chinese military. "In reality, the Nanjing Safety Zone was used as a base for fleeing Chinese troops," Ikeda noted. He added that many civilian deaths resulted from Chinese military activities within the zone, not direct actions by Japanese forces.

Aiding Chinese Forces

The narrative of mass killings spread quickly. On January 28, 1938, the Daily Telegraph and Morning Post reported the massacre of 20,000 people based on information from an anonymous missionary.

Chinese diplomat Wellington Koo, along with American writer Harold Timperley's book What War Means, played key roles in shaping global perceptions. Koo, representing China at the League of Nations, was instrumental in presenting the atrocities to the international community. Published in July 1938 and commissioned by the Chinese government's Central Propaganda Department, Timperley's book was specifically intended to influence Western opinion.

Both relied heavily on the testimonies of US missionaries like Bates, George Fitch, and John Magee. All three were central figures in the Nanjing Safety Zone. Despite their lack of operational records, Bates and Magee testified at the Tokyo Trials, perpetuating the figure of 300,000 civilian deaths.

Ikeda concluded that the Nanjing Safety Zone was "a mechanism to aid Chinese forces." Missionary James McCallum's confession that he participated in looting for Chinese soldiers reveals the reality behind these operations. After the zone's dissolution in February 1938, law and order returned to Nanjing, and the rumors of massacres began to fade.

RELATED:

- Nanjing Massacre: Where Did the 300,000 Death Toll Come From?

- 'The Rape of Nanking': Looking For the Spirit of 'Rashomon'

- Great Minds Don't Always Think Alike: Righting History and the Making of a New Japanese Textbook

Author: Daniel Manning

You may like

Japan Aims to Cut Antibiotics Reliance on China by Resuming API Production

Experts Say Nippon Steel Deal Has No Security Risk

Speaking Out | Deciphering a Chinese Military Plane's Violation of Japan's Airspace

EDITORIAL | Chinese Gov't Must Reflect on Its Responsibility in the Stabbing of the Japanese Boy in Shenzhen

The United Front: China's Great Global Campaign of Repression

China to Gradually Ease Seafood Embargo After Reaching New Deal with Japan, IAEA

沒有留言:

張貼留言

注意:只有此網誌的成員可以留言。